Aryn Baker is the senior international climate and environment correspondent at TIME. She covers the human impacts of climate change, as well as food security, oceans, climate migration, and extreme heat.

She lives in Rome, and has reported from more than 50 countries, as TIME's Africa bureau chief based in Cape Town, the Middle East bureau chief based in Beirut, Afghanistan and Pakistan bureau chief based in Kabul and as Asia correspondent based in Hong Kong. She has won multiple awards for her writing, reporting, and documentary film work.

At midnight on Thursday March 26, all of South Africa went into lockdown. For the next 21 days, no one is to leave their homes unless they are going to the grocery store, the pharmacy or to seek medical help. No dog walking, no jogging, no food delivery services. Only essential workers are exempt, and that list is small. When President Cyril Ramaphosa made the announcement on March 23, a week after shutting the nation’s schools, there were only 402 confirmed COVID-19 cases. But it was essential, he said, to “flatten the curve” before widespread outbreaks overwhelmed the country’s fragile medical system. By the time the lockdown went into effect, three days later, the number of cases had more than doubled. For most South Africans living paycheck to paycheck (if they have one at all) in small, multi-generational homes, the lockdown is a brutal, but necessary, blow. For the nation’s elites, insulated by yards, well-stocked pantries, and live-in staff, it is an inconvenience. For me, it is a relief.

My husband is in the category of people most vulnerable to COVID-19, the kind that the U.K. government suggests should stay at home for the next 12 weeks. He is far younger than the 75-year-old cutoff for eschewing all social contact, but he has a chronic disease, and is immunocompromised. But when no one else in our social group was taking precautions, it felt ridiculous to seriously follow the recommendations to stay home, and avoid family members who don’t.

Instead, we tried to compromise. “Contact tracing” for us wasn’t about figuring out who had been exposed to infected people; it was mentally tracking physical touch in areas where anyone could have been infected. If I wear plastic gloves to push the ticket button in the grocery store parking garage, should I change them before touching my steering wheel again? Do I disinfect my hands before or after touching the elevator button? What surfaces do my reusable grocery bags come into contact with at the shops, and what do they bring home to my kitchen counter?

Our extreme germ avoidance measures are messing with longstanding routines: yesterday at the pharmacy, my husband misplaced the receipts for his prescriptions in the flurry of disinfecting his hands, swabbing the credit card with alcohol, and removing the gloves he wore while shopping before he inadvertently touched his face. But the insurance company won’t reimburse us if we don’t have a receipt. Is it worth $530 to go back to the pharmacy—already crawling with potentially infected snifflers and coughers—to plead for a replacement?

Now with the lockdown, I can lay my anxieties to rest. Neither of us will be leaving the house anytime soon. At least until groceries run low.

Keep up to date with our daily coronavirus newsletter by clicking here.

Nearly five years ago my husband started complaining of low energy, then a tingling in his feet and hands. His fingers swelled up like sausages, and a few weeks later they curved into inflexible claws. His skin began to harden; when I wrapped my fingers around his arms, it felt like I was holding a wooden baseball bat. The edges of his lips and eyes thickened into raised white ridges. After a few false starts, we finally got a diagnosis: scleroderma, a rare autoimmune disorder that tricks the immune system into attacking the body’s soft tissues with excess collagen. It wasn’t just his skin that was at risk of hardening, but also his internal organs.

There is no cure for scleroderma, but immunosuppressants, along with an arsenal of steroids, anti-inflammatories and, weirdly, a common anti-malarial, can slow its progression. Not long after his diagnosis, T’s doctor told him that while life expectancy with scleroderma is low, those who made it past five years could expect a reasonable quality of life, with constant monitoring. T asked him if that meant he would be able to go off the medications, or if his energy would return. His doctor said he didn’t know; none of his patients had made it that far. In the meantime, he prescribed deep tissue massage to soften his skin, weekly physical therapy, regular visits and twice-yearly scans of all his internal organs to check for unseen hardening.

The four years since T’s diagnosis have revolved around regular visits with the gastroenterologist, the pulmonologist, the cardiologist, the ophthalmologist, the rheumatologist and the psychiatrist. Twice a week, he meets with a physical therapist who keeps his hands from reverting to the claws characteristic of the disease. He greets by name the staff at the hospital where he has gone three times in as many years to patch bleeding capillaries in his stomach wall—another symptom of the disease. At the pathology clinic he knows to ask for the only nurse who is able to find a vein through his thickened skin in order to draw blood. As Americans living in South Africa, we see his medical team more often than our own family. Cape Town’s hospitals are more familiar now than the streets where we grew up.

Now, that routine has been ripped away. Even before the lockdown, when coronavirus was more rumor than fact in South Africa, T’s doctors and physical therapist warned him to be careful, worried that his compromised immune system would put him at greater risk. Now we are more worried about them. For weeks, masks and hand sanitizer were impossible to find, and while both have trickled back onto the market, we need only to look to Italy and the United States to see South Africa’s future, where doctors and nurses are overwhelmed and under protected.

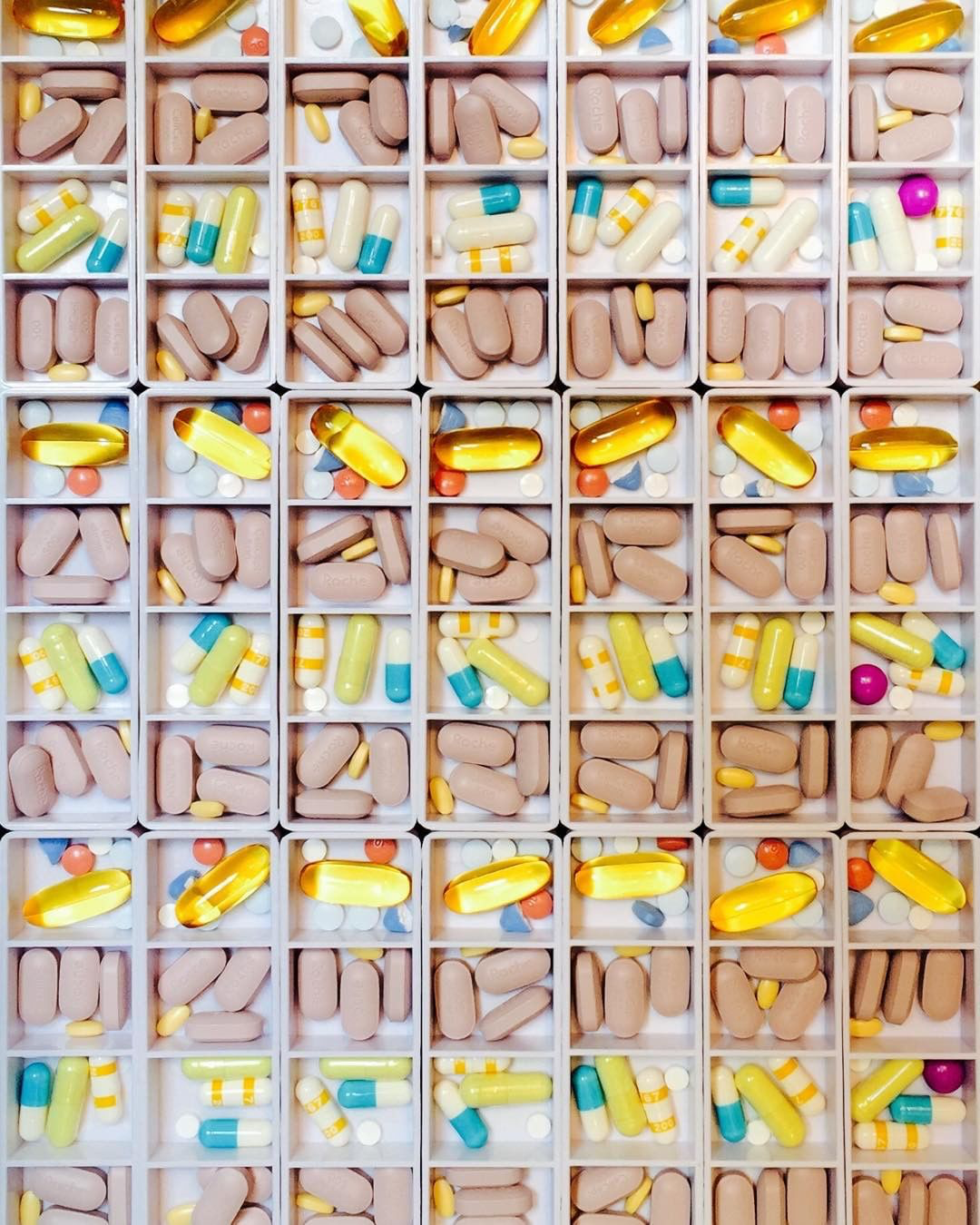

When the first cases appeared in South Africa, we weren’t particularly worried about a drug shortage. T’s drug regime, eight different medications, taken four times a day—didn’t include anything that would traditionally be used in treating a flu epidemic. Then President Donald Trump started touting, prematurely, the antimalarial hydroxychloroquine as a cure. Prescribed off label for rheumatoid arthritis, it’s one of the key elements of T’s treatment. There was a rush to stockpile, and India, one of the main producers, banned its export. T has enough to last the next month, but if hydroxychloroquine does turn out to be effective in treating COVID-19, it’s not clear if he will be able to get more. And even if he can, does the fact that he has been on it for the past four years make it less effective if he is then infected by virus?

When we got married, my husband and I had a deal. I would work, and he would manage the household and the childcare. It was an agreement that played to our strengths. I hate driving, grocery shopping, school pickups and running errands. When I’m not out on assignment, I could easily pass a week without leaving the house. T needs to get out. He craves social interaction, even the kind that comes from running routine errands. Now that every shopping cart or pharmacy pick up line is a possible vector of the disease, our roles are reversed. “This is the first time where I really feel like I’m disabled,” he told me the other day as I unloaded the groceries from the car.

In the first few months after his diagnosis, T often fell into a downward spiral of Dr. Google prognoses, reading out loud worst-case scenarios and scrolling through images of scleroderma-induced disfigurement. Now he reads how doctors in Italy, unable to treat everyone, have had to ration care for those who are most likely to survive, while letting others die. He wonders if he might be considered one of the lost causes.

As a correspondent based in Hong Kong in the early 2000s, I covered the SARS epidemic, and then bird flu. I spent several weeks in Liberia at the peak of the Ebola outbreak. I’ve reported on cholera, malaria, scabies and Zika. Diseases don’t scare me. But the idea of my husband being exposed to COVID-19 is paralyzing. Suddenly, the hospitals and doctor’s offices that have been a source of healing and comfort for the past four years are now a threat. The immunosuppressants T takes to control the scleroderma leave him vulnerable to any kind of infection. The coronavirus would have a field day in his scarred and vulnerable lungs. If his stomach starts bleeding again, we will have to weigh the risk of infection against the need for surgery. That is, if there is even room in the hospital at that point. We all have our Dr. Google driven downward spirals. Only this time, it comes from simply reading the news.

Please send any tips, leads, and stories to virus@time.com.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com