In the hours after Rosa Parks’ arrest on Dec. 1, 1955, Women’s Political Council president and Alabama State College professor Jo Ann Robinson used the school’s mimeograph machine to run off a set of flyers. “Another Negro Woman has been arrested and thrown into jail because she refused to get up out of her seat on the bus for a white person to sit down,” they read. “Don’t ride the buses.”

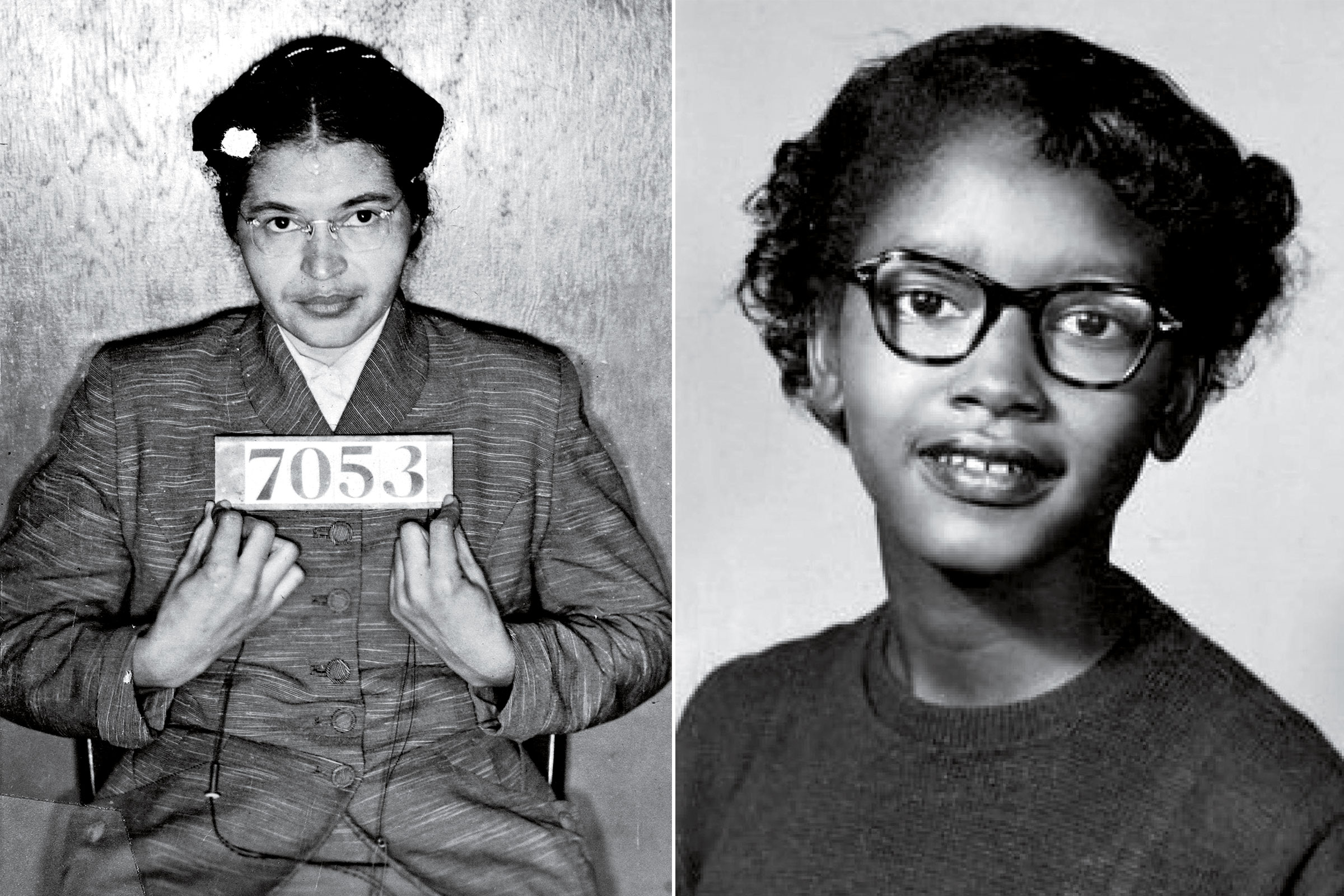

At the time, 75% of the people who rode the bus in Montgomery, Ala., were African American—and they knew there was strength in numbers. The boycott announced in that flyer lasted more than a year, and its seeds had been sown long before. Claudette Colvin, 15, had refused to give up her seat that March. So had Aurelia Browder, 36, in April and Mary Louise Smith, 18, in October.

Black Montgomery residents were aghast when two policemen dragged Colvin off the bus on March 2. Martin Luther King Jr., an activist minister who had just moved to the area six months prior, helped fight Colvin’s arrest—knowing that, with Brown v. Board of Education having struck down school segregation in 1954, the door was open for other legal challenges to segregation, says historian Jeanne Theoharis. But while Colvin was charged with violating the city bus segregation law, she was only convicted of assaulting a police officer, so a direct legal challenge to that specific law couldn’t be made.

Parks was well aware of Colvin’s case, having invited her to the local NAACP chapter’s youth meetings. So Parks didn’t resist when she was arrested, making sure she could be charged only with violating a segregation law. Years of involvement in the civil rights movement factored into this act of defiance; she has said she felt “pushed as far as I could stand to be pushed.”

In theory, this opened up a path to challenge the law, but civil rights leaders worried that Parks’ case could get stuck in state courts—an appeal by 1944 bus resister Viola White had been tied up in the Alabama courts—and that her NAACP activism could doom its chances. So in February 1956, lawyer Fred Gray filed a separate federal suit with Colvin, Browder, Smith and longtime bus rider Susie McDonald, 77, as the named plaintiffs. “No man is willing to be on the case,” says Theoharis, author of The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks. But four women, including two teenagers, were. A federal district court ruled intrastate segregated buses unconstitutional in Browder v. Gayle in June; the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the decision that November.

The boycott ended Dec. 20, 1956, having cost the city over $750,000 (about $7 million today). Facing death threats and unemployment, Parks and Colvin decided to move north, but their actions had already helped inform a new phase of the civil rights movement, and had catapulted King into a new leadership position.

The plaintiffs never received the recognition many male activists did, but their resistance informed both Parks’ decision to stay seated and the important legal fight that followed. With their victory, these women paved the way for the desegregation of public places, central to the civil rights movement. —Olivia B. Waxman

This article is part of 100 Women of the Year, TIME’s list of the most influential women of the past century. Read more about the project, explore the 100 covers and sign up for our Inside TIME newsletter for more.