If you’ve spent a lot of time on the internet in the last decade, you might immediately recognize this description: a toddler clenches his fist in front of a determined-looking face.

“Success kid” is one of the most popular online memes in history. But for the 2.2 billion people worldwide who report visual impairments or blindness, according to the World Health Organization, it is just one of thousands of images on the internet that are essentially illegible to anyone without full vision.

As millions like and re-share a viral post, people with visual impairments often find themselves locked out of the discourse. “It’s frustrating,” says Alex Stine, an 18-year-old recent graduate of the Kentucky School for the Blind who works in website accessibility. “When [I] come across [a meme], my screen reader reads ‘graphic.'”

Experts who spoke with TIME say there’s much more to be done to make memes universally enjoyable.

The most common practice for making images accessible online is through alternate text, better known as alt-text, which are descriptions embedded within a picture file. Screen readers, software applications that translate what’s happening onscreen into braille or audio, can recognize a picture’s alt-text and read it back for the user.

On TIME’s website, for example, a picture of Brad Pitt and Jennifer Aniston at the Screen Actors Guild Awards on Jan. 19 has alt-text that reads, “Brad Pitt grabs Jennifer Aniston’s right hand, as the two face each other smiling. Pitt has the trophy he won in his right hand, while Aniston’s left hand is raised.”

That would work for screen reading software. But consider what happens when things get meme-d: like this meme, with the photo next to a screen grab of a scene from the TV show Friends, showing Monica (Courteney Cox) opening the apartment door to find Rachel (Aniston) and Ross (David Schwimmer) in the hallway, with closed captions showing Monica’s line: “I’m sorry, apparently I opened the door to the past.”

Without embedded alt-text, this combination of images becomes uninterpretable for those with impaired vision. Cole Gleason, a Ph.D. candidate at Carnegie Mellon University and the co-author of Making Memes Accessible, a research paper analyzing the issue, says that the more fun aspects of daily life are often left on the back burner when it comes to accessibility work.

“There’s a tendency in accessibility-related fields for people to focus on making the workplace accessible, and making transportation accessible, because those are daily needs,” he says. “And people usually leave the recreational or silly or leisure activities to the later stages of accessibility, so humor was definitely not high on people’s priority lists.”

It’s not just about missing out on the fun of memes like “woman yelling at a cat.” “In the age of Donald Trump, memes are cultural capital. People use memes to kind of talk truth to power,” says Tasha Chemel, a 34-year-old college academic coach who lives in Brookline, Mass. and is blind. “They can be cute or hilarious, but I feel like people also use them to really communicate what the world we live in now is like. So it’s really hard to be left out of that conversation.”

Barriers to participating in meme culture can also directly affect social lives. Qualik Ford, a senior at the Maryland School for the Blind and the president of the Maryland Association of Blind Students, says the prevalence of memes makes it harder for him to connect with sighted friends. “Being a part of that culture is really important. Especially because I strive to have friends outside the blind community,” says Ford. “I wish we could connect on this level.”

And leaving out people with visual impairments doesn’t just affect how those with disabilities can communicate online. “Having a part of the population that is not involved in that part of the conversation deprives them of the ability to participate, which is a significant loss, but also deprives the community of their participation,” says Aser Tolentino, the accessible technology coordinator at the Society for the Blind, a nonprofit based in Northern California.

Both Facebook and Twitter provide shortcut keys to make their programs easier to use for those with visual impairments, and let users add image descriptions on their platforms. But it’s unlikely that every single person posting on their social media would take the time to add alt-text to their images, and many sighted users are unaware that they should or could.

“I honestly can’t say I’ve ever come across any alt-text on a meme,” Stine says. Tolentino believes having artificial intelligence (AI) create that text might be a way forward. “An automated solution is really the best response to something that is so user-driven at this point, since we don’t have that sort of expectation that this content be accessible,” he says.

Facebook did create an automated program, rolling out its AI-powered alt-text feature in 2016. But Shaomei Wu, a research scientist at Facebook AI, points out that the automated program still has limitations. For instance, the algorithm purposefully does not identify gender—so as not to assume anything about photographed subjects—and only works once it reaches a high level of confidence in reading the image. Facebook has worked to adapt the program over the years, but Chemel feels it remains imperfect. The automatic alt-text appears with language like, “image may contain,” along with a list of “objects recognized by the computer vision system,” according to a Facebook research paper on the program. In other words, it’s not nearly as descriptive as the alt-text actual humans come up with, which can describe a person’s facial expression, attitude and actions in much greater detail.

People who are visually impaired or blind often turn to more welcoming spaces online. One Reddit group, r/blind, has more than 7,000 members and enforces strict rules against posting inaccessible content, and there are Facebook groups and Instagram accounts that do the same. But Chemel is still waiting for inclusion everywhere. “I’m really glad those spaces exist. I think right now they’re necessary. But I think they’re segregated spaces,” she says. “That doesn’t necessarily make me feel that included.”

In any case, it’s not easy to explain visual humor without ruining the joke—and even harder to automate that effort. “If you could figure that out, I think you would be able to procedurally generate comedy,” Tolentino says. Lydia Chilton, a co-author of Making Memes Accessible and a member of the computer science faculty at Columbia University, says the key is gleaning “which ways of translating the memes into an accessible format produces the actual humorous response.”

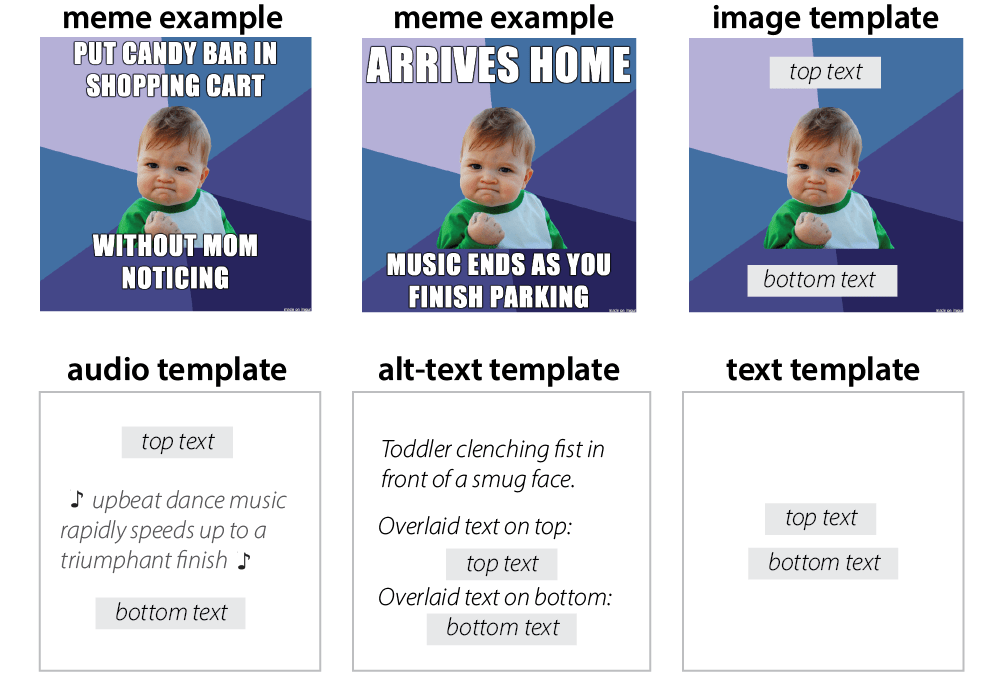

She and Gleason, along with other researchers from Carnegie Mellon, developed a program that recognizes image-macro memes—memes consisting of one image overlaid with text, in which the image remains the same across variants, but the text changes, such as “success kid” or “distracted boyfriend”—and generates an audio template that helps translate variations of the meme.

For example, in the image below, the researchers offer templates for explaining a meme. One plays specific music that would theoretically get across the tone of the meme, and makes the text pasted on the image legible for screen readers, while the second just has regular alt-text describing the image. The final panel shows a more basic template for describing “success kid”—just the image macro with top and bottom text.

They tested their system on 10 blind or low-vision people who rated how funny the meme explanations were. As a result of that study, published by the Association for Computing Machinery and presented at the accessibility conference ASSETS in October of 2019, the researchers identified five guidelines people should keep in mind when writing alt-text in order to best translate an image’s humor: explaining the characters’ actions, emotions and facial expressions, the source (such as TV or film) of the image and anything distinct about the background. Chilton says the team hopes to meet with tech companies to present the results of the study and explain how they can make their products more accessible.

Ford hopes up-and-coming tech innovators will take note of the issue and build accessibility into their systems from the start, which is how Apple created its iPhone screen reading software, VoiceOver. “You know how you add salt after you make something? They need to make sure the salt’s already in the mix,” he says.

As the community awaits further innovation, Chemel and others are doing what they can to try to understand memes. Chemel recently had a friend describe “business fish” to her, and it cracked her up.

But she’s looking forward to the day that she knows she’s no longer missing anything. “Honestly, I don’t even know what I don’t know,” Chemel says. “That’s the part of this that’s so hard—it’s that there’s so much out there that I just have no idea exists.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Rachel E. Greenspan at rachel.greenspan@time.com