Seven years after the fatal gang-rape of Jyoti Singh on a bus in New Delhi horrified India and sparked nationwide protests, a crowd gathered last Monday to mark the anniversary of her attack. That same day, Dec. 16, a former lawmaker from India’s ruling party was convicted of raping a 17-year-old girl.

The dichotomy highlighted the plight of India’s women, who, despite the outrage after Singh’s rape and murder, still face unprecedented rates of sexual violence. “Nothing has changed for women at all,” says Asha Devi, Singh’s mother, who was at Monday’s gathering with her husband to remember their 23-year-old daughter, who has become known as Nirbhaya, or “fearless.” “So many of these incidents are continuing to happen.”

Each day, about 90 rapes are reported in India, but many more go unreported due to the fear and stigma surrounding sexual violence. In just the past month, high-profile cases have included a 27-year-old veterinarian who was gang-raped and murdered; a four-year-old girl who was allegedly raped by her neighbor; and a six-year-old girl who was found by family members lying in a pool of blood after local media reports said she was allegedly kidnapped and raped by her neighbor in northern India. Last Monday, Kuldeep Singh Sengar, the former lawmaker from India’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), was convicted of raping a 17-year-old girl in 2017. He was sentenced to life imprisonment on Friday. The case came to national attention last year after the victim tried to set herself on fire because of alleged police inaction. Multiple Indian politicians are currently facing sexual assault charges.

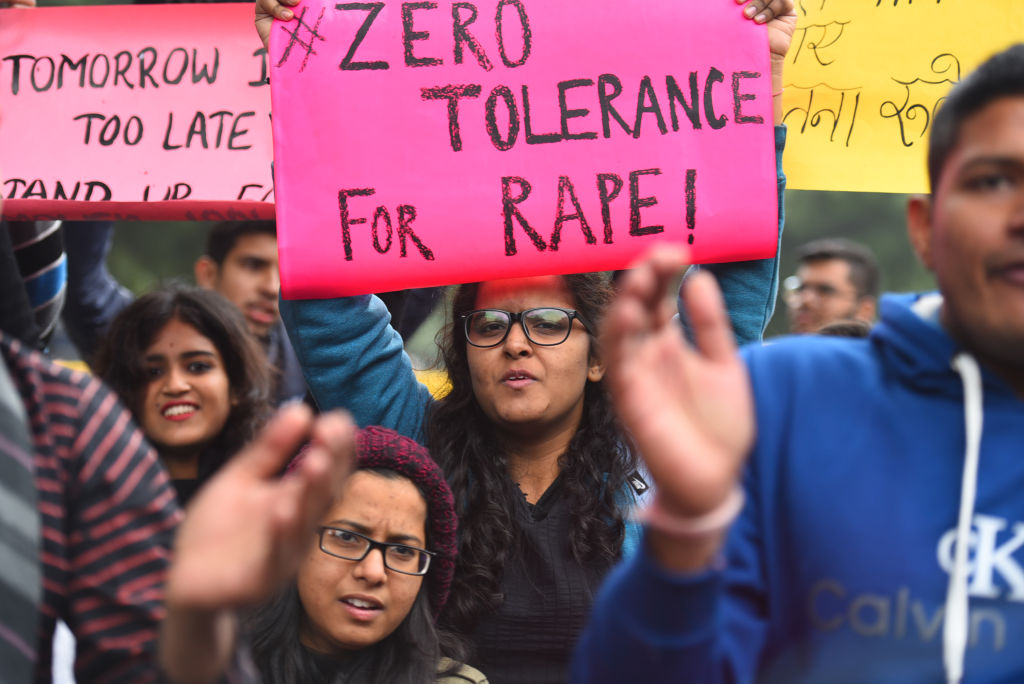

The 2012 Nirbhaya case, as Singh’s attack came to be known, shook “the whole conscience of society,” says Ranjana Kumari, the director of India’s Centre for Social Research. “Everywhere reacted to it.” The government implemented legal reforms, including mandating harsher punishments for rapists, and launched initiatives aimed at improving safety for women. In 2014, shortly after Prime Minister Narendra Modi was elected, his government pledged a “zero tolerance” policy on violence against women and said it would “strengthen the criminal justice system.”

But for the most part, activists say little has changed. “Here we are. Unfortunately asking the same questions,” says Jayshree Bajoria, author of a 2017 Human Rights Watch report on violence against women in India.

The biggest question: Why, despite the outcry over Jyoti Singh’s murder and government promises of change, does sexual violence remain endemic in the country?

India was the most dangerous country in the world for women due to the high risk of sexual violence and of being forced into slave labor, according to a 2018 survey by the Thompson Reuters Foundation.

From 2016-2017, the number of reported cases of rape reached 32,559 according to government statistics, but experts agree that far more occur than are reported. That number also does not take into account attempted rapes. “Rape statistics in India must be taken with a large carton of salt because they don’t tell the whole story,” says Kavita Krishnan, a women’s rights activist and the Secretary of the All India Progressive Women’s Association.

Those who do report rape and sexual assault often struggle to be taken seriously. Women interviewed by Human Rights Watch researchers say they are often not believed, either by police, medical professionals or in court. Survivors and witnesses receive little protection from retaliatory attacks: in December, a woman died after being set on fire while on her way to testify against her alleged rapists. And, according to a Human Rights Watch report, some medical professionals still conduct the degrading and inaccurate “two-finger” tests under the guise of being able to measure a woman’s past sexual experience through an internal examination. The World Health Organization says the practice, which cannot determine if a woman is a virgin or if she’s had several sexual partners, has no merit, yet the evidence from the procedure has been used during trials to assert that a rape survivor had “loose” or “lax” morals.

Sometimes, the very authorities who are supposed to enforce the law are accused of sexual violence. On Dec. 15, police entered the Jamia Millia Islamia University campus in New Delhi and sexually assaulted female students who were among a crowd protesting a controversial new law, the Citizenship Amendment Bill, according to local media reports. Police turned the lights off in certain areas so that CCTV cameras would not capture the violence, according to a statement by an activist and an advocate.

Many women say they are always afraid for their safety. “I’m constantly edgy and aware of who’s looking or who’s not. There is this constant feeling of fear,” says Saloni Chopra, an Indian actor who has spoken about her experiences of sexual and physical abuse. “It’s not something you can shrug off. It’s exhausting. You feel helpless.”

“You also know that once everyone is done raging, people are going to go back to their normal lives,” Chopra adds. “It’s hard to change the conversation.”

The Nirbhaya case kicked off a wave of sustained protests in India and a more open dialogue about sexual violence, eventually prompting a response from the government. “A cultural silence was broken. It was a moment in time where it seemed that India was breaking the cultural taboo of speaking about sexual violence,” says Bajoria, the HRW researcher.

Since then, the women’s movement has swelled; in response to calls from politicians and members of the public for women to stay at home to stay safe from rape, female activists have said they will not trade their freedom for safety, says Krishnan. India has also had its own MeToo movement, which gained momentum in 2017. After law student Raya Sarkar published a list on Facebook of alleged sexual harassers in academia, women began sharing their stories of sexual assault and harassment. The movement led to women in the media and entertainment industries speaking out about their own similar experiences in 2018.

But greater awareness of the problem has not brought greater safety. In fact, women’s rights activists in India say things have gotten worse in recent years.

“It has become much more difficult for feminist voices to be heard this time around,” Krishnan says of her attempts to speak up about violence against women. She has received daily rape and death threats since 2014, during the election campaign of now Prime Minister Narendra Modi, whose BJP party has been accused of protecting its own lawmakers accused of sexual misconduct.

“Seven years ago I could protest against the government and the supporters of the government were not threatening me with rape and death. Now they are,” Krishnan says. “This is a very real and present danger. That is the picture of India today. It’s a terrifying situation.”

Amid the public pressure that followed the Nirbhaya case, the government, then led by the Congress Party enacted significant reforms. It developed guidelines for the health care system to provide better treatment to survivors of sexual violence, and it created the Nirbhaya Fund in 2013, which provides state money to help pay for initiatives focused on women’s safety and on assisting female victims of violence.

That same year, new laws expanded the definition of sexual offences to include sexual harassment, voyeurism, and stalking, and mandated stricter punishments for offenders.

But activists say these reforms have been poorly implemented and enforced. “I always say: we have pretty strict laws. What we need is surety of punishment [rather] than stricter punishment,” Bajoria says.

The government has not spent a large amount of the Nirbhaya Fund; local news reports indicate that less than 20% of the allocated funds have been used. Staff at police stations and hospitals may receive training on how to handle sexual assault and rape cases but often lack sensitivity, sometimes leaning toward not believing survivors, Bajoria says.

Krishnan says courts are often hostile environments. “For those women who are currently going through rape trials, they are facing (…) humiliating questions about their sexual life and their sexual morality,” Krishnan says.

And it remains difficult to pursue justice in India’s bureaucratic justice system, as cases get extended and postponed; it often takes years to reach verdicts. There are around 133,000 pending rape cases according to government statistics.

While India’s legal system is slow at addressing sexual assault and rape cases, high-profile incidents often result in public outrage and calls for the death penalty. After the gang-rape and murder of the veterinary doctor in the city of Hyderabad in late November, the woman’s charred remains were found near the underpass of a motorway, leading to calls to hang the accused and claims of police inaction. (Three police officers were suspended after the victim’s family accused them of not acting quickly enough when the woman was reported missing.)

Later, other police officers took the alleged perpetrators to the location of the incident, then shot and killed them, claiming the men had tried to escape. Advocates say this kind of vigilante justice is not the answer, either. “There is no justice,” says Kumari, the director of India’s Centre for Social Research, a women’s rights advocacy group. “There was no conclusive evidence that these were the same boys… There was no due process followed.”

Activists say the solution lies in practical and big-picture changes, including establishment of courts specializing in crimes against women to expedite justice in rape cases, changing attitudes toward women’s roles in society, and less objectification of female bodies. “Some people getting real punishment will certainly make the law look like a deterrent,” Kumari argues.

Bajoria says there’s no single thing that will fix the problem. “We need enforcement, police accountability, a more sensitive [and] responsible criminal justice system, health care system, courts and a whole concerted campaign to deal with gender-based discrimination,” Bajoria says. “All of it. India will need to do all of this.”

But big changes, they say, are dependent on women pushing for their share of power, given men’s failure to tackle the problem effectively.

“These are all very toxic masculine governments. For them, women’s rights, violence against women is not a priority at all. Forget about priority. There is insensitivity at large,” says Kumari. “They may have come to power… screaming at the top of their voice that they will do something about safety for women but when you look at what they rolled out it’s absolutely not enough.”

“As long as these men are sitting in power nothing will happen,” she adds.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Sanya Mansoor at sanya.mansoor@time.com