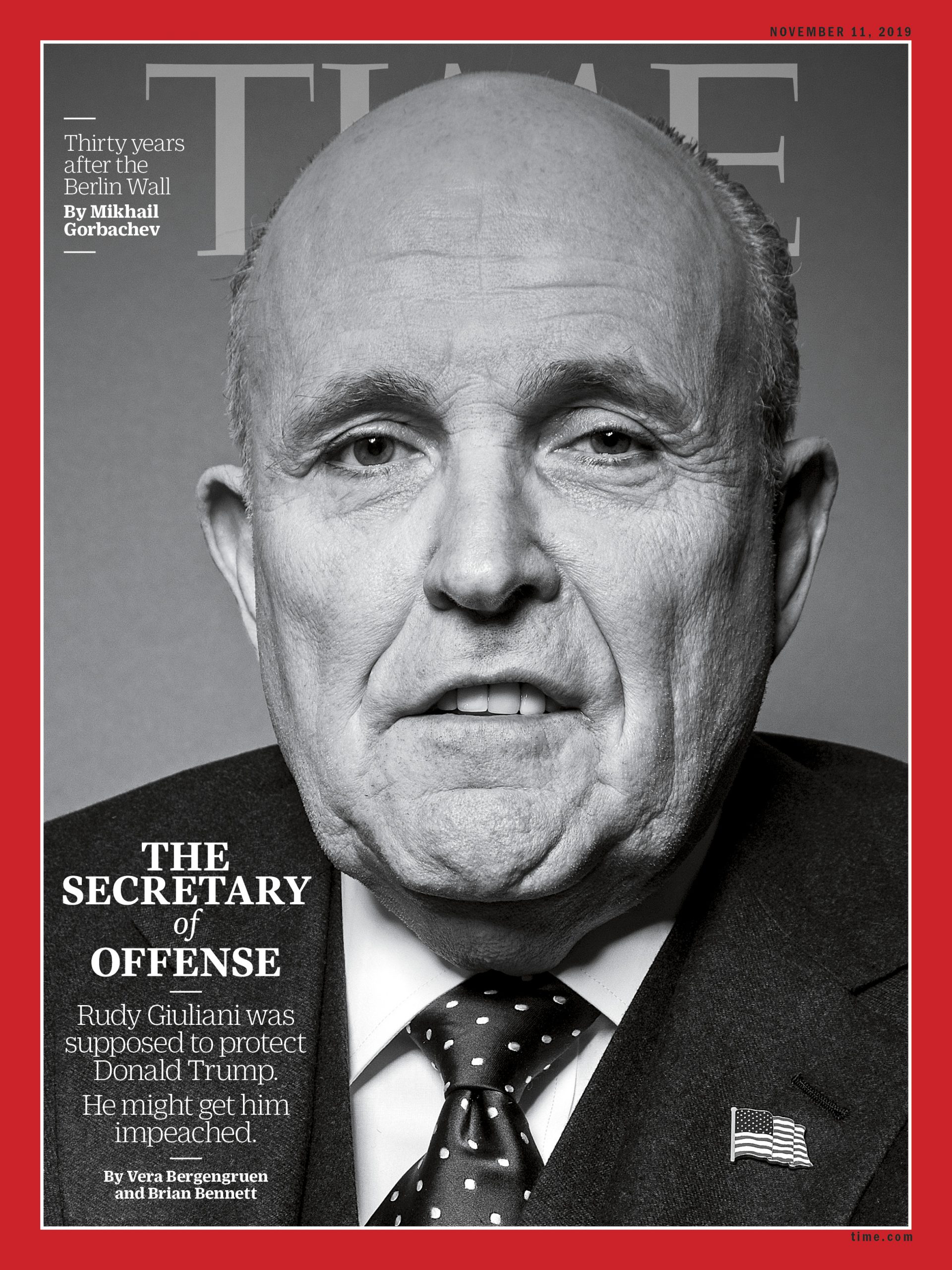

In the storied career of America’s most famous mayor, the last five weeks have been quite a chapter. During a shouting match on CNN on Sept. 19, Rudy Giuliani denied and then, 30 seconds later, admitted to playing a central role in President Donald Trump’s efforts to get a foreign country to investigate his top 2020 rival, Joe Biden. Five days later, Giuliani went nuclear on a radio host during a joint TV appearance, shouting, “Shut up, moron, shut up!” as he tried to drown out accusations that he was making things up. Trump’s personal lawyer capped it off on Oct. 16 by pocket–dialing a reporter for NBC News and inadvertently leaving a lengthy message as he talked to an unidentified partner about potentially lucrative business in Turkey and Bahrain.

Some people were worried. Giuliani’s longtime associate Bernard Kerik says he keeps getting asked, “Is he O.K.?” Walter Mack, who ran an organized–crime unit for Giuliani back when they were prosecutors in Manhattan in the 1980s, says he wonders the same. Mack says if he saw him now, “I would talk to him as a friend and a fellow prosecutor, and just be certain he was getting good advice and that he was not losing sight of his own standards and morals.” Kerik, who was Giuliani’s top cop in New York and later served three years in federal prison for tax fraud and other crimes, talks regularly with his old friend. Giuliani, he says, is just “vocal” now that he doesn’t have to worry about “running for office.”

But it’s a bewildering turn of events for a person who at one point in his career had been among the most admired public figures in the country. Giuliani was always colorful. As mayor, he was a New York archetype come to life: the fast-talking, Bronx-accented wheeler-dealer, complete with mistresses, sharp suits and primo seats at Yankee Stadium. And many loved him for being an iconoclast. He was the law-and-order mayor who cleaned up Times Square, a Republican who believed in gun control and gay rights, a self–described pro-choice Republican as at home at the city’s glimmering galas as at the televised perp walk of a criminal. With exuberant F-you energy, he seemed to embody the city itself. And for the brief post-9/11 moment when Americans were all New Yorkers, the whole country became Giuliani’s constituents too.

His latest brush with history is revealing a darker side, something that suggests not just Giuliani unbound, but untethered from the values he once espoused. And as the House impeachment inquiry accelerates, and witness after witness describes Giuliani as the prime enabler behind what Democrats say are impeachable offenses committed by Trump, Giuliani’s behavior may end up having historic consequences.

So what is going on with him? Interviews with those close to the former mayor, and those who have crossed paths with him in his work for Trump, say Giuliani’s transformation has a simple source: over the past 18 months, he has violated that unwritten rule of American public life that you can pursue money or political power, but not both at once.

There’s nothing particularly exceptional about riding the revolving door from having power to making money and back again, and for years Giuliani has pursued both with relish. After leaving the mayoralty, Giuliani cashed in with book deals; high-priced speaking engagements; and a lucrative, if murky, consulting business that counted Qatar, Purdue Pharma and a range of controversial foreign personalities as top clients. After a brief and failed attempt to get back into power as a candidate for President in 2008, he returned to the money game. By 2018, he was making between $5 million and $10 million a year.

What’s different now is that Giuliani is doing both at the same time. In the 18 months since Trump hired him as his personal lawyer in April 2018, Giuliani has become a kind of shadow Secretary of State even as he has maintained his foreign consulting business. He has often been treated as a de facto envoy of the U.S. government while abroad, at the same time receiving lucrative consulting and speaking fees from foreign officials and businessmen.

His quest has been enabled by Trump, who entrusted Giuliani with Cabinet-level influence. When Energy Secretary Rick Perry pushed Trump in May to meet with Ukraine’s new President, for example, Trump told him to “visit with Rudy,” according to an interview Perry gave the Wall Street Journal. And an aide to former National Security Adviser John Bolton told congressional impeachment investigators that Giuliani was running a parallel foreign policy, outside the normal channels of U.S. diplomacy. Meanwhile, as Trump’s cable-news defender and then his personal lawyer, Giuliani remained technically a private citizen, unencumbered by long-standing ethics rules designed to prevent officials from using public service for personal gain.

And gain he did: where the salary of the actual Secretary of State, Mike Pompeo, was $210,700 last year, until the past few years Giuliani seemed to enjoy a lavish, approximately $230,000-a-month lifestyle that includes six homes, access to private jets and 11 country-club memberships, according to his recent divorce–court filings published by the New York Times.

Giuliani says there’s nothing wrong with continuing his consulting for foreign clients while at the same time representing the President. “Of course I don’t mix the two things,” he told TIME in a phone interview. He said people pay him as a lawyer and security expert, and because he has “done some remarkable things that nobody else has ever done.” “Everything I’m doing now is similar to what I did in the past,” Giuliani says.

His critics say that is exactly the problem. As he jetted around mixing his access to Trump with his personal business, they began asking, Whose interests was he serving? America’s? Trump’s? His own? Much of the work that Giuliani has done remains undisclosed—few know which foreign interests are paying him, how much they’re paying or what exactly they’re getting in return.

But amid the many self-dealing scandals besetting the Trump Administration, Giuliani’s adventures went largely ignored, at first. And he might have happily continued his money power play but for one thing: Ukraine.

Things began going wrong around April, when special counsel Robert Mueller’s probe was drawing to a close. Fighting Mueller had been job one for Giuliani and had brought him closer than ever to the President. Serendipitously, Giuliani now says, he had uncovered another scandal. This one involved a series of conspiracy theories in Ukraine, including a search for dirt on Joe Biden’s son Hunter, who had been paid to sit on the board of a Ukrainian energy company when Biden was Vice President. This new scandal would come to obsess the President as he prepared to run for re-election.

It was while working to substantiate these conspiracy theories that Giuliani appears to have gotten himself into trouble. In August 2018, he had gone into business with two Soviet-born émigrés who have since been arrested on charges that they illegally funneled foreign money to political campaigns in the U.S. Their lawyer resisted a request for documents from the House impeachment inquiry in part on the grounds they have assisted Giuliani in other work for Trump.

Now Giuliani’s successors in the U.S. Attorney’s office in Manhattan are looking into his own business dealings in Ukraine, including meetings he held with government officials there, according to reports in the New York Times and Wall Street Journal.

How much damage will come from Giuliani’s 18-month romp through the swamps of money and power is now the question of the Trump presidency. Current and former senior Administration officials worry that he has been putting unsubstantiated Ukrainian conspiracy theories into Trump’s head and that Trump doesn’t know or understand that Giuliani has business interests that may be served by some of the advice he is giving the President. Most of all, they blame Giuliani for Trump’s push during a July 25 phone call to get the Ukrainian President to investigate Biden, a 2020 political rival.

But Giuliani is confident Trump won’t turn on him: “He’s 100% in my corner and loyal to me as I am to him.” And for now, Trump doesn’t seem to be aware of, or at least worried about, what Giuliani’s murky mix of business and diplomacy may have gotten him into. “Rudy Giuliani’s a great crime fighter,” Trump said on Oct. 28 in response to a question from TIME. “He’s always looking for corruption, which is what more people should be doing. He’s a good man.”

At some point soon, Trump may face the reality of a trial in the Senate over charges he abused his office. Some of those allegations will be linked to Giuliani’s efforts in Ukraine. Giuliani’s increasingly erratic behavior suggests that his gravy train of easy deals tied to political power may come to an ugly end. The question is what else will come to an end with it.

No one believed him. It was October 2018, and Giuliani had just stepped out of a three-car motorcade into a light drizzle in the Armenian capital of Yerevan. An eager gaggle of government officials in dark suits deferentially escorted him as he walked toward a memorial to the Armenian genocide, while reporters live-streaming his visit asked questions about U.S. foreign policy. “I am not here in my capacity as a private lawyer to President Trump,” Giuliani said, “I am here as a private citizen.”

It was clear that no one intended to treat him like one, and that was just fine with Giuliani. Although he was there to speak about cyber–security at a Russian-led trade conference, his trip had all the trappings of an official visit. Armenia’s Defense Minister briefed him in private, and the government released a formal readout of the meeting. News reports identifying Giuliani as a White House envoy scrutinized his answers on whether the U.S. would formally recognize the Armenian genocide. Sharing the stage with Sergey Glazyev, a longtime adviser of President Vladimir Putin who has been under U.S. sanctions since Russia’s 2014 invasion of Ukraine, Giuliani dangled potential U.S. cooperation on cybersecurity with a Russian–led trade bloc. One Armenian who met with the former mayor said, “He may be the contact person between Yerevan and Washington.”

Giuliani told TIME his paid speech was “perfectly appropriate” and one of “over 1,000 speeches” he has given for a fee, but refused to discuss details. Giuliani has been known to charge as much as $200,000 for a public speech and up to $175,000 a month to be retained for security consulting.

Giuliani’s foray in Armenia is just one of his many gigs. Around the same time that he traveled to Yerevan, he was paid by a global consulting firm to send a letter calling for changes to Romania’s anti-corruption program, a position that contradicted the U.S. State Department’s stance. He attended an event by Congolese lobbyists that left them with the impression he would work with them on the Trump Administration’s position on sanctions on the country. His firm secured a $1.6 million deal to do security work in a Brazilian province in the Amazon.

After joining Trump’s inner circle, his dealings became more freewheeling. He regularly conducted business on his cell phone while holding court at upscale cigar clubs in New York and Washington, and after nearly two decades of work abroad, foreign officials, businessmen and journalists knew where to reach him.

But even as he has become an increasingly ubiquitous public figure, much of his work remains undisclosed. Even top government officials are often grasping for signs. White House officials were surprised, for example, when Trump seemed receptive to the possible extradition of Fethullah Gulen, a Turkish cleric who lives in the U.S. and is a political opponent of the current Turkish leadership, according to the Washington Post and New York Times. Giuliani told TIME he spoke to Administration officials about Gulen, but in relation to a client in a separate matter.

Giuliani says that the questions about his business dealings are “insulting.” He maintains that he is paid only for his expertise—not for representing foreigners or lobbying the Trump Administration, which would force him to register as a foreign agent. He left his law firm Greenberg Traurig in May 2018, and touted that he was working for the President for free out of patriotic duty.

Friends defend his business endeavors. “He’s always wanted to make money since he left as mayor, so what?” says Jon Sale, a former Watergate prosecutor who knew Giuliani when they both worked as federal prosecutors in Manhattan. “In a lot of circles, Rudy’s stature is not what it was. But I’ve been with him in some places and some parts of the country where people still continue to revere him. People come up to take a picture with him and for autographs and say, ‘Thank you Mr. Mayor for what you’ve done.’”

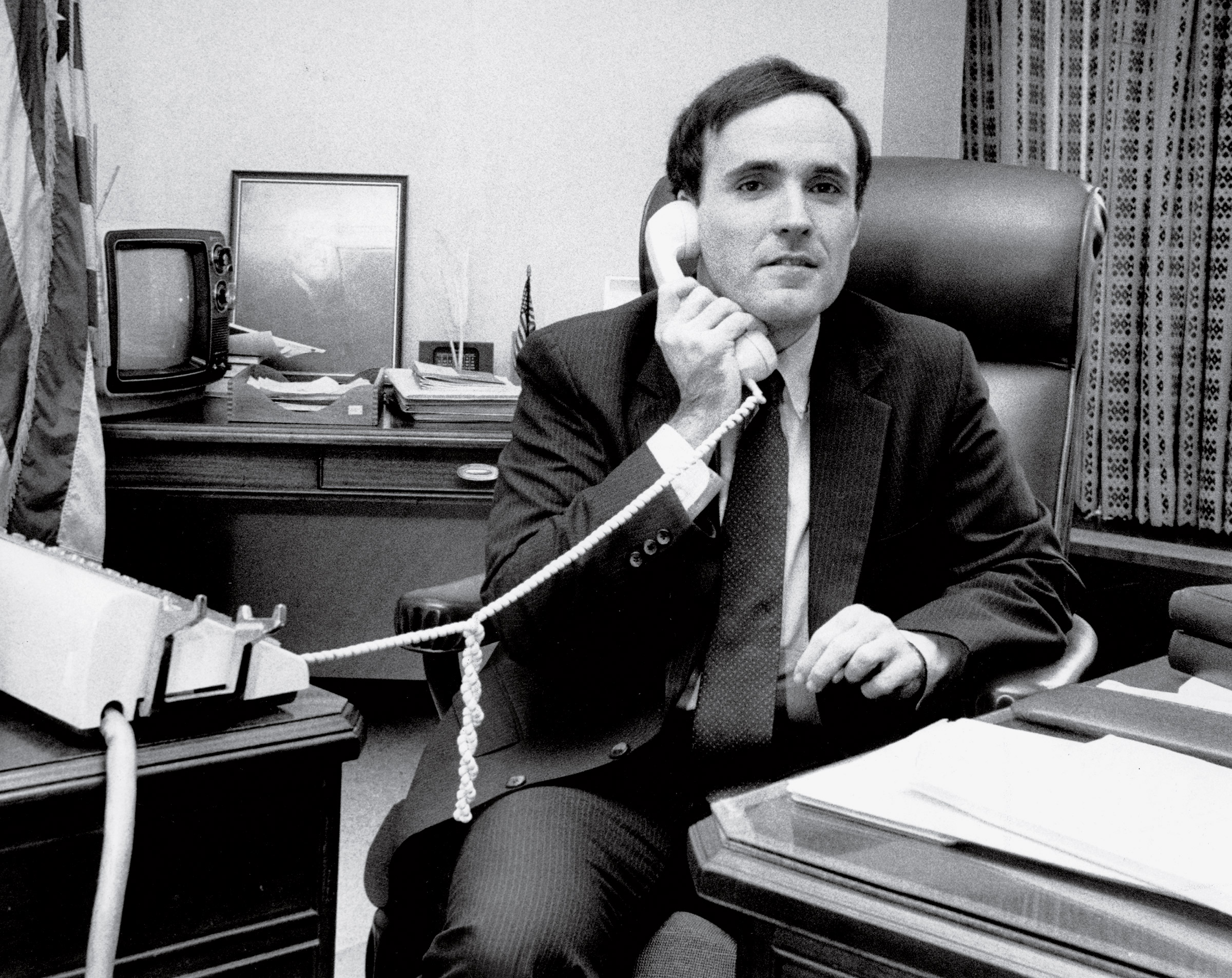

After winning election as mayor in 1993, Giuliani cracked down on crime, using often controversial tactics to “clean up” the largest city in America. But it was his response to the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks that made him an international celebrity. The destruction of the World Trade Centers terrified America, and his reassuring presence on the streets of the city made him an icon of resilience. In 2001, TIME named the “mayor of the world” the Person of the Year.

But if a successful political career had led him to the peak of power in his hometown, a lifetime of government salaries hadn’t made him rich. In June 2001, his divorce lawyer famously declared from the steps of a Manhattan courthouse that the then mayor had only $7,000 to his name.

After he left office, he cashed in on his fame. First he wrote a best-selling book, Leadership, and lined up hundreds of high-priced speaking engagements. In one period from 2006 to 2007, Giuliani made more than $16 million, $10 million of which came from delivering 108 paid speeches around the globe about leadership and security.

Giuliani also went to work for a variety of high-paying but controversial clients both as a lawyer and as a security consultant. His consulting firm signed a contract with Qatar around 2005 at a time when the Gulf state’s security forces were under scrutiny for letting the Sept. 11 mastermind Khalid Sheikh Mohammed slip away from the FBI in 1996.

Buoyed by the wave of goodwill and his celebrity, he launched a bid for the 2008 Republican presidential nomination. He quickly cemented himself as the early front runner, with 34% of likely Republican voters saying they would vote for him in a March 2007 poll. But his run imploded in the wake of questions about his foreign lobbying and liberal positions on social issues. His abrasive style and fixation on terrorism didn’t help, leading Biden to deliver the now famous line that there were only three things Giuliani ever mentioned in a sentence: “A noun, a verb and 9/11.”

After his run for the ultimate position of power failed, he seemed to fade from the headlines and turned back to making money. In his business as an international security consultant, he again took on controversial clients, including a Turkish gold trader accused of laundering Iranian money. He took several trips to Russia and former Soviet countries through TriGlobal Strategic Ventures, a secretive international consulting company that has provided image consulting to Russian oligarchs and others close to the Kremlin.

Having failed to win the White House himself, Giuliani may have been as surprised as anyone when his old friend Donald Trump’s unexpected election offered him proximity to Oval Office. Giuliani and Trump knew each other for decades. Both were raised in the outer boroughs of New York City, made their names in Manhattan, sought the limelight early in their careers and became regulars in New York’s gossip pages.

In 2000, at the Inner Circle dinner, a rollicking convention of big names and comedians, Giuliani wore a lavender dress and blond wig for a spoof video in which Trump leers at Giuliani and says, “You know, you’re really beautiful.” When Giuliani sprays perfume on his chest, Trump rubs his face in it. “Oh you dirty boy,” Giuliani says in a high-pitched voice, and slaps him.

Giuliani did not publicly endorse Trump until two weeks before the New York State Republican primary. But when he did, he was all in. It was Giuliani who went on all five Sunday-morning shows to defend Trump after the Oct. 7, 2016, release of a recording of Trump talking about grabbing women by their genitals.

Ironically his current position as unofficial envoy of the President came about only when he didn’t get the Administration job he had hoped for. After Trump’s election, Giuliani turned down top spots at the Justice Department and the Department of Homeland Security, hoping instead to be named Trump’s Secretary of State. Giuliani lobbied hard for the position, touting as credentials his 150 foreign trips to more than 80 countries as a globe-trotting consultant. But Trump and his son-in-law, Jared Kushner, were concerned that Giuliani’s celebrity would make him unmanageable at State. When it became clear Giuliani wasn’t going to get the job, he withdrew from consideration, saying he “could play a better role being on the outside and continuing to be his close friend and adviser.”

That role was a boon for Giuliani financially, but he still had the itch for real power. He saw an opportunity in Trump’s frustration with his legal team’s failure to protect him in the Russia investigation. For more than a year, Trump had been fuming, “I don’t have a lawyer,” invoking the memory of Roy Cohn, the notoriously ruthless New York attorney and power broker, according to the Mueller report. Trump said he wanted “someone who got things done.” In Giuliani, who had taken to television news shows to repeatedly attack Mueller, he found his Roy Cohn.

For months, Giuliani had a good run under Trump. Even while many close to the President warned that relying on Giuliani could be his downfall, the former mayor was able to carry out both his freewheeling deals and Trump’s wishes without restraints. As White House advisers came and went in a steady stream of firings and resignations, Giuliani endured. But it was ultimately his full-throttle pursuit of the thinly sourced Ukraine scandal that may have historic consequences for him, the President and the country.

In August 2018, Lev Parnas and Igor Fruman, a pair of Soviet émigrés based in Florida, entered Giuliani’s life. Parnas paid Giuliani a $500,000 retainer for what he said was legal and business advice for his fraud–prevention firm. Up until then, Parnas and Fruman had been unknown and unconnected. But soon enough, they were able to get access to prominent Republican circles, in part by flaunting their association with Giuliani.

They posted photos of themselves enjoying dinner at the White House, including photos with Trump. They shared photos of their breakfast with Trump’s son Don Jr. and drinks “celebrating” after the conclusion of the Mueller probe with the White House legal team. As they jetted around the world, they boasted of political connections that could open doors. “They told us they would bring Mayor Giuliani to the dinner with them if we honored them,” Farley Weiss, the president of the National Council of Young Israel, an umbrella group for a network of Orthodox synagogues, told TIME in an email. The group honored the two with an award in March.

Their lucky streak didn’t last for long. In early October, Parnas and Fruman were arrested at Dulles airport outside Washington after they bought one-way tickets to Vienna. They were charged with the federal crime of scheming to buy U.S. political influence by funneling foreign donations to politicians. Court filings alleged they distributed $675,500 in campaign contributions to at least 14 Republican candidates.

Unfortunately for Giuliani, the pair’s arrest shone a spotlight on their other dealings with him as well. Parnas and Fruman had been serving as middlemen between Giuliani and Ukrainian officials in Giuliani’s quest to dig up politically damaging information on Democrats for Trump. Prosecutors said they had lobbied then Texas Representative Pete Sessions to push for the ouster of the U.S. ambassador to Ukraine, whom Giuliani considered an obstacle to investigating the Bidens. When the former mayor had to cancel his trip to Ukraine in May amid accusations of political meddling, Parnas reportedly went to Kiev presenting himself as a representative of Giuliani to seek out information about the Bidens.

And then there’s the question of the half million dollars Giuliani received from Parnas’ fraud-prevention firm. He has claimed he knows “exactly” where it came from. “I’ve seen the wires,” he told the Washington Post. (The money was reportedly briefly in Fruman’s account.) But it’s unclear how Parnas and Fruman had access to those kinds of funds. A TIME review of Florida court filings show that since the mid-2000s, they left a trail of bankruptcies, failed businesses, evictions and lawsuits for failing to pay back loans.

All this has put Giuliani in the sights of the same prosecutor’s office he once led. An investigation by the U.S. Attorney’s office in the Southern District of New York has been scrutinizing his connection to Parnas and Fruman, as well as his bank records and meetings with Ukrainian officials, according to the Wall Street Journal. Giuliani has denied any wrongdoing and said that prosecutors “can look at my Ukraine business all they want.” Giuliani insisted to TIME he is not in any legal jeopardy.

“I have to presume they’re innocent,” he told the New York Times about Parnas and Fruman. “None of those facts that I see there make any sense to me, so I don’t know what they mean.”

How consequential this particular aspect of the multifaceted Ukraine scandal will prove remains unclear. Testimony by multiple nonpartisan Trump Administration officials has shown that Giuliani was the main driver behind Trump’s efforts to force Ukraine to investigate the Bidens. To strengthen the case for doing so, Giuliani has touted an affidavit from a former Ukrainian prosecutor alleging he was fired in March 2016 for investigating the gas firm that employed Biden’s son. That document, TIME reported in October, was produced by the legal team for a Ukrainian billionaire currently living in Vienna who is fighting extradition to the U.S. This summer, his American lawyers hired Parnas as their translator.

One thing that’s clear is that Giuliani is already feeling the financial consequences of the Ukraine scandal. And he’s not happy about it. In his accidental voicemail to NBC News, Giuliani can be heard saying, “The problem is we need some money.” After a pause, he says, “We need a few hundred thousand.” The intense scrutiny of the House investigation has forced Giuliani to pull out of lucrative opportunities. He had been planning to return to Armenia this year for the same Kremlin-backed trade conference he had attended with great fanfare in October 2018.

But when word leaked out about his travel plans just days after the whistleblower complaint implicated him in pressuring Ukraine, it caused a public backlash. Just hours after confirming the paid speech, he reversed himself and announced he wouldn’t be going back to Yerevan after all. —With reporting by Tara Law and Sanya Mansoor/New York; Simon Shuster/Kiev; and Molly Ball, Tessa Berenson and Abby Vesoulis/Washington □

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Vera Bergengruen at vera.bergengruen@time.com