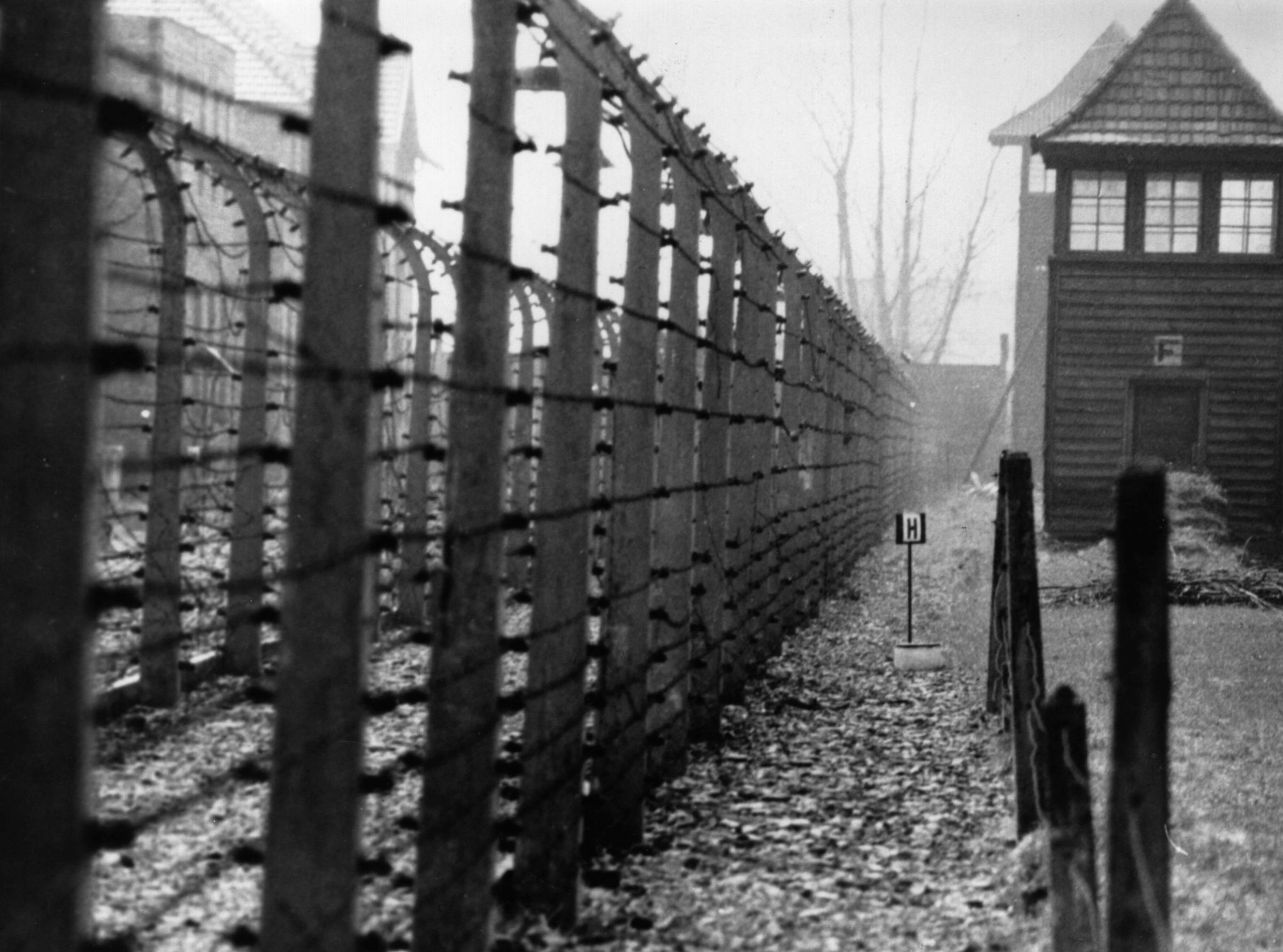

When Allied forces broke open the gates of concentration camps in 1945, they discovered not only piles of corpses and dozens of gravely ill inmates but also survivors who were seeking revenge. Many of those who were liberated sought retribution not just against the Germans but against former Jewish functionaries in the camps and ghettos as well. Freed inmates lynched and beat Jews who, as ghetto policemen, had surrendered them and their family members to the Nazis or who, as kapos in concentration camps, had harassed or abused them.

In a contemporary culture that tends to venerate Holocaust survivors, the idea that a victim might have behaved in a questionable manner seems inconceivable. The prevalent view today, however, was not the dominant one for the first 20 years after World War II, when many believed that the victims as a group, and especially those who had served in leadership positions in ghettos and camps, shared responsibility with the Germans for the catastrophe that had befallen them.

When survivors immigrated to Mandatory Palestine, the same kinds of intra-Jewish clashes that had been seen in Europe erupted in public spaces there. But the institutions in pre-state Israel that operated similarly to the honor courts that had addressed such disputes in Europe were inadequate to the problem. Media commentators and public figures called upon the heads of the Yishuv, the Jewish community in Mandatory Palestine, to alleviate tension by establishing a public committee of socially prominent figures to deliberate these cases and issue social punishments. The leadership chose, however, not to establish such a committee, deeming social penalties insufficiently severe for those accused of cooperating with the Nazi mission to annihilate the Jewish people.

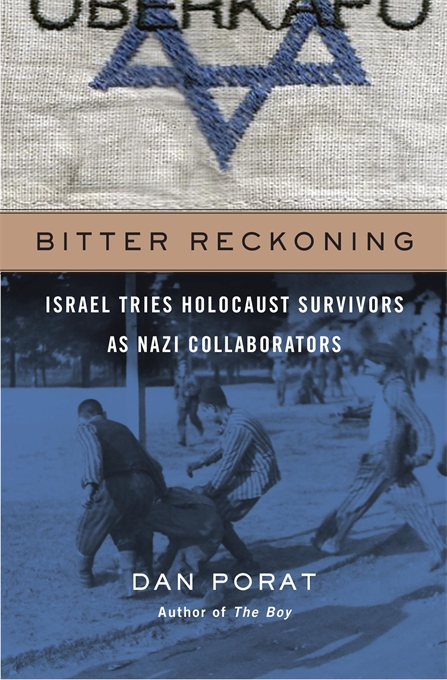

It was only after the establishment of the State of Israel and after a repeated demand from a high-ranking police officer that the Ministry of Justice drafted a bill setting up a system for trying functionaries in criminal court, where they would face their accusers. The Nazis and Nazi Collaborators Punishment Law, passed by the Knesset in 1950, inaugurated what became known as the kapo trials, which would go on for the next 22 years.

Over those two decades, the kapo trials went through four main phases, moving from an initial perception of Jewish ghetto and camp functionaries as perpetrators equivalent to the Nazis to a final perception of them as victims.

During the first phase (August 1950–January 1952), alleged collaborators were subjected to uncompromising treatment. Legislators formulated the law so as to put Nazis and their Jewish collaborators on equal footing, a perspective that failed to take into account the antithetical worlds in which they lived. Only in the sentencing phase did the law make provision for the functionaries’ position as victims themselves, allowing in very limited cases some measure of leniency. In the first year and a half of the kapo trials, district courts sentenced six former kapos to an average of almost five years of imprisonment and issued one death sentence, in the case of Yehezkel Jungster.

In the second phase (February 1952–1957), functionaries were cast not as Nazis but as Jewish collaborators of the Nazis. This phase began after the court sentenced Jungster to death; to prevent any further such rulings, the prosecutors, who seem to have never anticipated that the court would issue a death sentence, rushed to change all indictments that included charges that could potentially carry the death penalty. Shortly thereafter, the Supreme Court overturned Jungster’s death sentence. In doing so, it adopted the new line drawn by prosecutors between Nazis and their Jewish collaborators: the former could face charges of crimes against humanity and war crimes, but the latter could not. In all other respects, the justice system continued to view the functionaries as equal to the Nazis, and the trials continued. Outside the courtrooms, however, doubts began to emerge as to whether functionaries should be prosecuted at all.

In the third stage (1958–1962), the legal system viewed most functionaries as men and women who had committed wrongs but had done so with good intentions. From this point forward, prosecutors filed charges only against functionaries they believed had aligned themselves with the Nazis’ aims. During this period some survivors had also come to believe that it was time to put aside past controversies and move on. Others, however, still called for putting alleged collaborators on trial.

The Eichmann trial in 1961, and the trial of Hirsch Barenblat two years later, marked the shift to the fourth and final stage of the kapo trials (1963–1972). In this phase the legal system viewed functionaries as ordinary victims, a change that signaled a full reversal from the initial view of functionaries as guilty until proven innocent. Eichmann’s prosecutor drew a stark distinction between innocent Jews, including functionaries, and evil Nazis. The negative image of those who were victims but at times acted in ways that benefited the perpetrator vanished.

The story of these trials is as yet little known, because only in recent years has the Israel State Archives made the transcripts of some of these trials publicly available.

Initially, when I began poring over the thousands of pages of transcripts of these trials, I had a hard time taking a position about the appropriateness of prosecuting these alleged collaborators. At first I asked myself how one could judge those who had gone through hell on earth, men and women who had lost entire families, experienced unimaginable hunger, and lived under conditions of brutal oppression, striving only to survive. Then I began reading the harsh stories recounted by survivors in the courtrooms, and my view swung to the opposite side. One witness described how, in 1942, the commander of the Jewish police entered the town orphanage, climbed to the attic, found dozens of pale children, dragged them down the stairs, and handed them over to the Nazis to be transported to Auschwitz. Was this not an act that deserved punishment? Yes, I thought, it was the Nazis who had subjected these women to the inhumane conditions of the camp, but did the status of victim permit the kapo to beat this inmate and many others so viciously, even when no German was in sight?

In considering these cases, I oscillated from viewing these inmates as innocent scapegoats to seeing them as criminals. It was an essay by Primo Levi on what he called the “gray zone” that first laid out for me the irresolvable tension between the perceived guilt of such victims and our inability to judge them. Levi, an Italian-born Holocaust survivor, writes, “The condition of the offended does not exclude culpability, which is often objectively serious, but I know of no human tribunal to which one could delegate the judgment.” Oppression, he holds, does not sanctify victims. Functionaries—not minor ones such as lice checkers or messengers but rather kapos, who frequently used violence—served, in Levi’s words, as “collaborators” and so are “rightful owners of a quota of guilt.” Yet he goes on, “I believe that no one is authorized to judge them, not those who lived through the experience of the Lager [camp] and even less those who did not.”

The human stories revealed in the kapo trials demonstrate the complexity of the position of victims, a complexity that we must comprehend if we wish to truly try to understand—and to the degree possible—overcome the Holocaust.

Excerpted from Bitter Reckoning: Israel Tries Holocaust Survivors as Nazi Collaborators by Dan Porat, published by Harvard University Press. Copyright © 2019 by Marona Inc. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Dan Porat is also the author of The Boy: A Holocaust Story, and a teacher and researcher at The Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com