Seventy years ago today was among the greatest and most horrible days of World War II. On this day, April 29, in 1945, American forces liberated Dachau — the first of the Nazi concentration camps, and one of the largest — and discovered boxcars full of corpses, along with 32,000 living inmates whose condition was not much better.

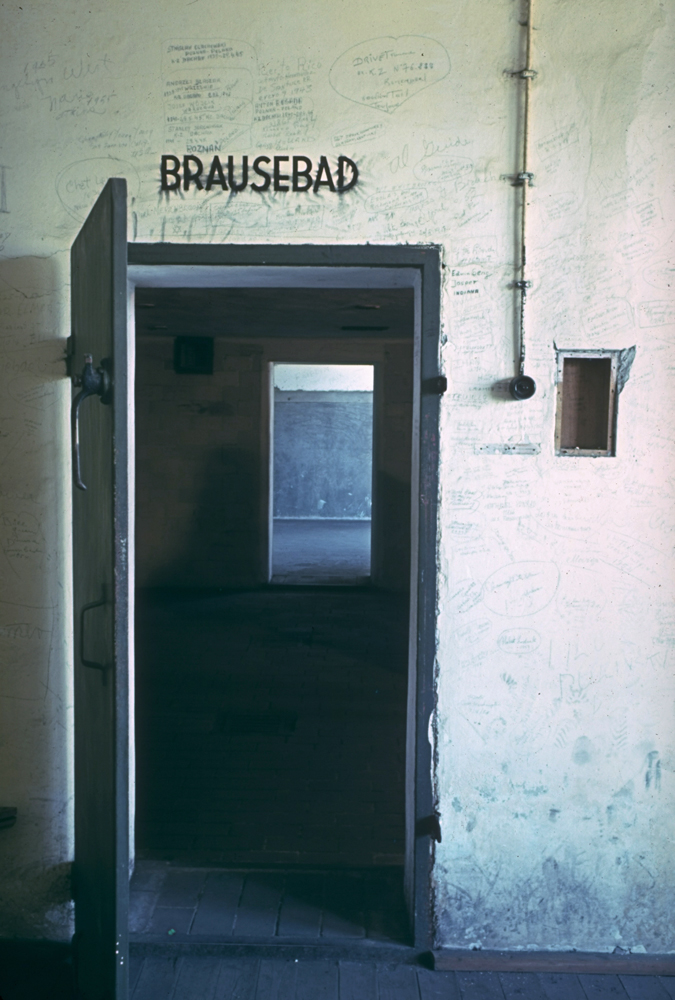

A TIME correspondent, Sidney Olson, accompanied the soldiers who freed the survivors; his report was one of the grimmest, most gripping dispatches ever filed from the front. In his plain, straightforward style, he painted a stark tableau of some of the worst brutality in the history of humanity, describing stacks of naked, emaciated bodies and evidence of the sadism to which they had been subjected — like the hooks from which they were hung by their necks or thumbs, according to the whims of their guards.

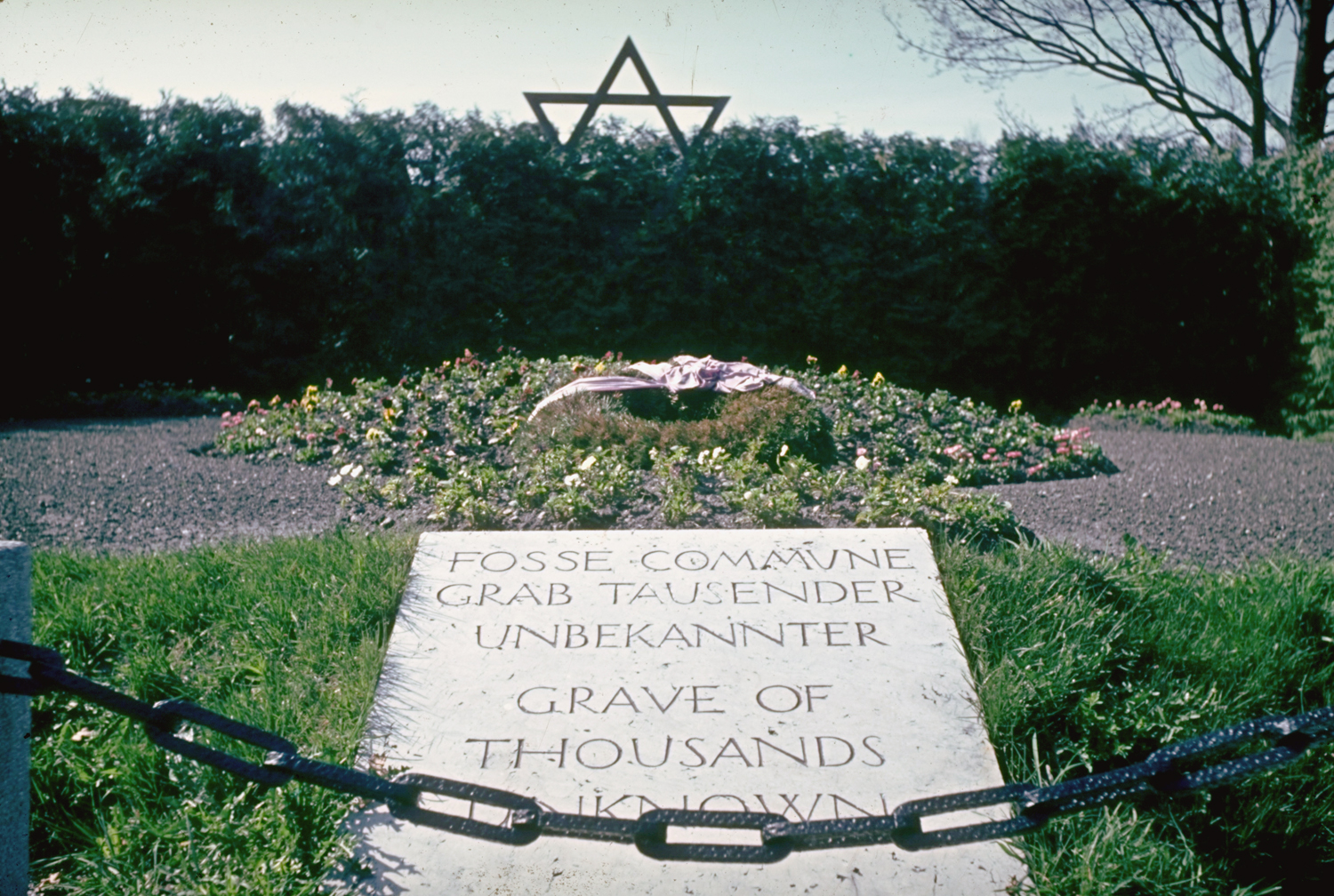

Even more disturbing, however, was his account of the starving, sick and hysterically happy survivors, kissing and cheering their liberators. Most were political prisoners of various nationalities, including Russian, French, Yugoslavian, Italian, Polish and even Indian. According to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Dachau, the site of a former munitions plant 10 mi. outside Munich, had begun as a prison for communists, social democrats and other political opponents of the Nazis, but expanded over time to encompass gypsies and Jehovah’s Witnesses, criminals and homosexuals, as well as an increasing number of Jews.

The camp had also become a medical lab where Nazi physicians tested potential treatments for malaria, tuberculosis, and hypothermia — and explored methods of desalinating seawater and stopping heavy blood loss — using the prisoners as test subjects. Those who survived the experiments were often left physically and mentally disabled.

But that was true for most of the camp’s survivors, whether or not they had endured this particular form of torture: It was all torture.

Near the end of 1945, TIME profiled the 200 children under 16 who had been taken to a nearby monastery after being rescued. Aid workers, trying to nurse them back to health through good nutrition, were stymied by the psychological wounds that couldn’t be healed with food. Older children couldn’t stop talking, frantically telling and retelling the stories of how they had stoked crematorium fires and cut down the bodies of the hanged. Infants and toddlers, too, had suffered much more than near-starvation.

“The 18-month-old babies could not sit up at first—and they never smiled,” TIME reported.

Even Olson, who matter-of-factly put the unspeakable into words, was dumbstruck by the way the gaunt, haunted faces of the survivors lit up with desperate euphoria when they were freed.

“The eyes of these men defy my powers of description. They are the eyes of men who have lived in a super-hell of horrors for many years, and are now driven half-crazy by the liberation they have prayed so hopelessly for,” he wrote. “Again & again, in all languages, they called on God to witness their joy.”

Read the original 1945 report, here in the TIME archives: Dachau

Ghosts in the Sun: Hitler's Personal Photographer at Dachau, 1950

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Breaking Down the 2024 Election Calendar

- How Nayib Bukele’s ‘Iron Fist’ Has Transformed El Salvador

- What if Ultra-Processed Foods Aren’t as Bad as You Think?

- How Ukraine Beat Russia in the Battle of the Black Sea

- Long COVID Looks Different in Kids

- How Project 2025 Would Jeopardize Americans’ Health

- What a $129 Frying Pan Says About America’s Eating Habits

- The 32 Most Anticipated Books of Fall 2024

Contact us at letters@time.com