Jessica Post is stuck in traffic 63 miles south of Washington, D.C., when she pulls an iPhone to her ear. “How’s everything going with your family?” she asks a contender for Virginia’s state legislature this fall. “We are all in for your run. I was reading about your opponent the other day. He sounds like a real piece of …” Here, she remembers that TIME is tagging along. “Work,” she finishes.

Calls like this consume a lot of Post’s time these days. The 39-year-old president of the Democratic Legislative Campaign Committee (DLCC) is leading an unheralded but critically important campaign to win back state offices for the party after eight years of deep losses during Barack Obama’s presidency. The consequences go far beyond which states may be prevented from joining lawsuits trying to dismantle Obamacare or restrict abortion rights. The candidates who win state legislative races later this year and in 2020 will decide who wields power in Washington for a decade.

Every 10 years, politics rewrites itself, starting with the decennial Census. Legislatures in 31 states use the findings to draw the borders of federal congressional districts. In some, nonpartisan commissions draw the lines clinically. In others, it comes down to who has the Sharpie and the least amount of shame. The map is due to be reset before the 2022 midterm elections, which means lawmakers elected as soon as this year may determine where the congressional battlegrounds will be into the 2030s. “State legislatures are the building blocks of our democracy,” Post tells TIME during a break from candidate calls in the DLCC office five blocks from the White House. “It’s a level of the ballot that’s been forgotten. But state legislators draw the lines, so control of Congress in many ways is decided by rules put together in state legislatures.”

For decades, Democrats have largely overlooked these local offices to their detriment. Terry McAuliffe, a former Virginia governor, remembers arriving at Democratic National Committee (DNC) headquarters to start his job as party chairman in February 2001 and making a troubling discovery: lawmakers in the states were starting to draw new district maps, and no one at the DNC was paying attention.

“Not a thing had been done on redistricting,” McAuliffe recalls. “In the past, I don’t think our party understood the importance of legislative chambers.”

They soon learned. In 2010, the Tea Party wave washed 681 Democrats out of legislative seats right before new battle lines could be drawn, according to data tracked by the National Conference of State Legislatures, giving the GOP the opportunity to cement its advantage in competitive congressional districts. In all, Democrats lost 958 state legislative seats during Obama’s presidency.

Post, a meticulous Missouri native who previously held top roles at Emily’s List and the DLCC, rejoined the group in 2016 with a mandate to reverse the slide. Since then, Democrats have flipped 283 state legislature seats, with a net gain of six chambers. Post has tripled the organization’s staff and quintupled its fundraising target from $10 million to an estimated $50 million for the 2020 cycle.

Other Democratic groups have begun investing in down-ballot contests too. In August, Emily’s List announced a $20 million effort to help flip legislatures. Former Attorney General Eric Holder, with the backing of Obama and the help of McAuliffe, has started a group called the National Democratic Redistricting Committee, which is dedicated to the process of drawing new borders. Flippable, a grassroots Democratic group focused on winning statehouse races, has already funneled $125,000 into Virginia and is eyeing eight other states in 2020.

But Democrats are aware they’re still playing catch-up in a space the party has long neglected. “Republicans have been doing this for decades,” says Amanda Litman, the executive director of Run for Something, a group that recruits young progressives to stand in down-ballot elections. “If we don’t have Democratic control of state legislatures ahead of redistricting in 2021, Republicans will take back Congress in 2022, and that’s the end of functioning government in Washington.”

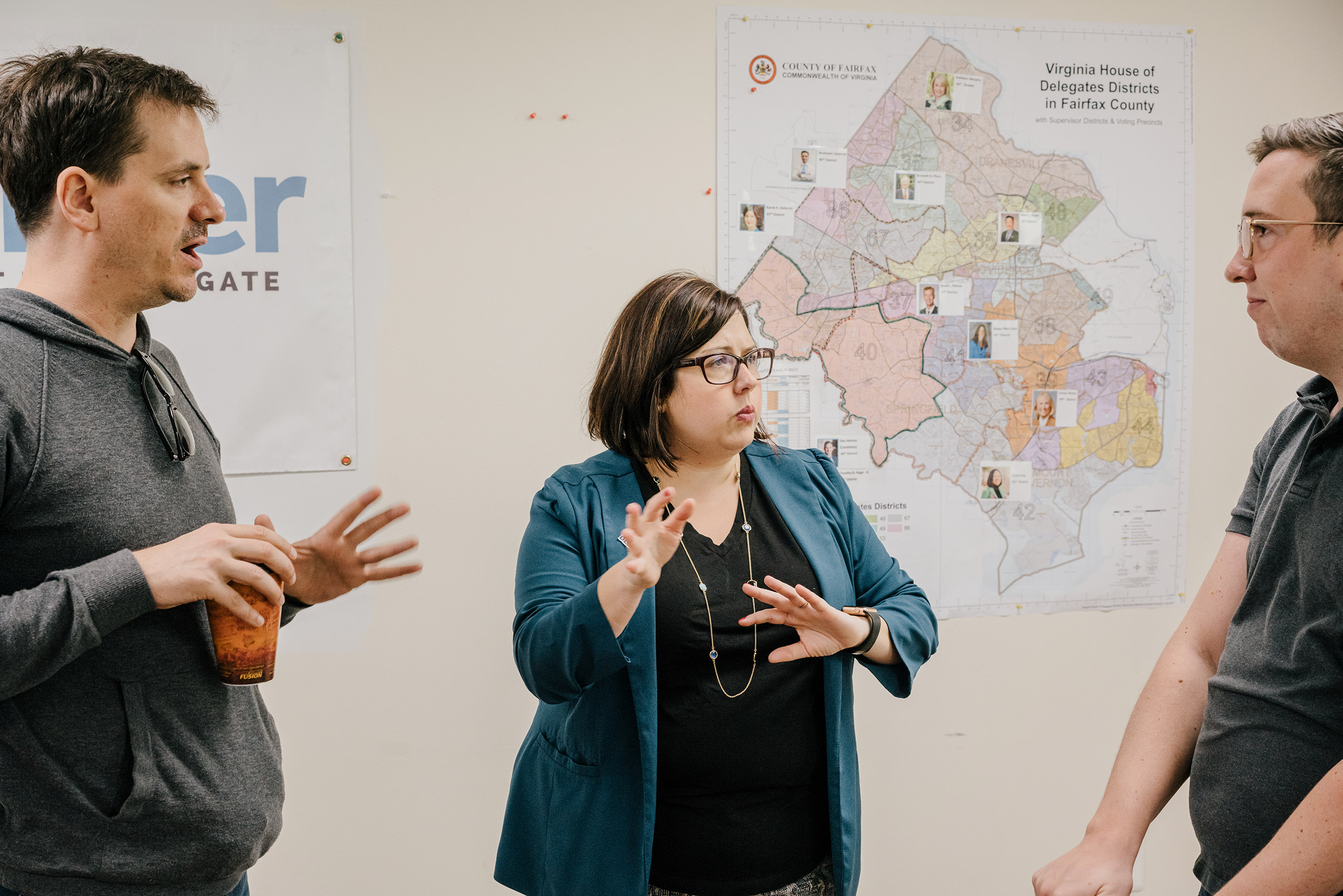

On a recent Saturday afternoon, Post huddled with Virginia’s Democratic brain trust on the 20th floor of an office building in downtown Richmond, Va. The group gathered around a conference table, clicking through a slideshow of district maps, media budgets and historical vote tallies. Post spends a lot of time on the state these days. Virginia, New Jersey, Mississippi and Louisiana hold the only statewide legislative elections in 2019, and Post is using the commonwealth to test her assumptions, technology, vendors and data, shelling out $1 million and counting in the process. The conference room looks down on the capitol, where the DLCC needs to flip two seats for Democrats to claim the majority in the state’s house of delegates and two more to do the same in the senate. Doing both would give the party the trifecta–control of both legislative chambers and the governor’s mansion.

Post asks for a briefing on what house strategists have gleaned from the first six focus groups they’ve organized in Virginia. She wants to know how many Republican-held districts they’re targeting where Democrat Ralph Northam won his race for governor in 2017, and how many Tim Kaine won when he ran for U.S. Senate in 2018. (The answer is nine and 12.) How many districts, she asks, are Democrats leaving uncontested?

The answer is not many. Democrats have built a machine in Virginia, seeded in part with cash Post started sending southward as early as December 2018. There are 91 Democratic candidates for the commonwealth’s 100 house races on Nov. 5, and 35 senate hopefuls for the chamber’s 40 spots, which include three senate districts that voted for Hillary Clinton for President in 2016 but are currently represented by Republicans. “They are running to build the party,” house caucus executive director Trevor Southerland says.

The DLCC’s play has indirect effects too. For instance, the group has featured one of its favorite candidates, activist Sheila Bynum-Coleman, in national fundraising messages; 21% of her donations have come from out-of-state donors as a result. “I don’t think I would have gotten the attention if it weren’t for the DLCC,” says Bynum-Coleman, who is challenging the current speaker of the house of delegates in a Richmond-area district.

At the conference table, Post keeps asking questions about the blend of TV and digital advertising in specific races. “That’s an expensive district,” says Kristina Hagen, executive director of the Virginia Senate Democratic Caucus, of one seat in the Washington media market. “There is a world in which we can get away with digital and cable.”

Post still urges them to book TV early. “Reserve aggressively,” she says.”We have to win this.”

The Democrats can afford pricey TV ads because they’ve been chipping away at the GOP’s longtime financial advantage in the states. The three major Democratic committees in Virginia have already spent $2 million, compared with just a quarter of that invested by their GOP counterparts. (Virginia’s GOP house speaker Kirk Cox, Bynum-Coleman’s opponent, has added about $500,000 through his PAC to help his Republican colleagues.) “I’d think Democrats should be disappointed if they don’t flip both chambers,” says Kyle Kondik, an analyst at the University of Virginia’s Center for Politics. “At the same time, I don’t think it’s a slam dunk that they will in fact flip them both.”

It’s easy to see how Post convinces donors that these low-profile races are worthy investments in the Trump era. Republicans “won and rigged the maps,” Post says. “They re-engineered everything and put in place durable majorities.” Now she wants Democrats to have control when it comes time to define the next 10 years.

Post’s counterpart at the Republican State Leadership Committee (RSLC), Austin Chambers, is working hard to prevent that. Chambers says his group will raise more money than ever, and plans to top the $40 million it spent in the 2015–2016 election cycle. In August, the RSLC announced that former Republican National Committee finance chairman Ron Weiser, a fundraising legend, was joining the group. “They should be optimistic. Because when you’re at rock bottom, the only place you have to go is up,” Chambers says of the Democrats. “We’re glad they finally discovered this thing called state legislators.”

But Chambers has been warning donors that Post’s efforts cannot be written off, lest Republicans suffer the way their opponents have at the state level. “What happens in a few state legislative races over the next year and a half will determine the balance of Congress for at least the next decade or longer,” Chambers says. “The importance of this cannot be overstated. It’s as serious as anything we’ve ever faced.”

The path toward Republican dominance at the state level began more than three decades ago, when Democrats, in the wake of Jimmy Carter’s loss to Ronald Reagan in 1980, focused their energy on presidential politics in the 1984 cycle. The current dynamic dates back to 2010, when Karl Rove wrote a Wall Street Journal column laying the groundwork for what came to be called the Redistricting Majority Project (REDMAP). The RSLC’s REDMAP program recruited and funded state-level candidates aggressively. REDMAP spent $30 million to the DLCC’s $8 million that year. The effort netted GOP total control of 11 legislatures and a trifecta in nine additional states. In turn, the party started drawing congressional districts it liked.

Republicans still start with a leg up in the battle for the states in 2020. The GOP controls 52% of seats in all state legislatures, with majorities in 62% of state legislative chambers and total control of state government in 22 states, to Democrats’ 14. But many of the chambers have narrow GOP edges. Democrats stand to pick up majorities in seven chambers–including those in Minnesota, Arizona and Virginia–if they can win 19 specific races.

Meanwhile, the gains Democrats have made in recent years may be difficult to defend. President Donald Trump was a liability for Republicans in 2018, when he wasn’t on the ballot and his approval sat at 40% in Gallup’s final pre-election survey. But Trump could wind up helping GOP candidates in 2020, when the party hopes his massive political machine will boost fortunes of candidates all the way down the ballot.

It’s also possible that existing Democratic-led statehouses overstep their mandates and provoke a backlash. In typically blue Illinois, for example, lawmakers declared abortion a fundamental right, no matter what the Supreme Court may say. When Republicans in the Colorado statehouse objected to the pace of change under Democratic control, they raised procedural hurdles and demanded the measures be read aloud. Democrats responded by having five computers read a 2,023-page bill simultaneously–so quickly the text was unintelligible. The issue went to court, where the Republicans won.

The party that wins control of Richmond in November and other state capitals in 2020 has decisions to make. Republicans may want to cluster African-American voters into one district to make the rest of the area easier to win. Democrats may want to spread those voters out more evenly. In Northern Virginia, both parties may want to minimize the number of seats that have to buy ad time in the expensive D.C. market. Armed with enough data, it’s possible to draw lines that enhance the odds of winning again and again. “We were so pleased as Democrats that we won this Congress,” Post says of the 2018 elections. “But the truth is, it’s just a rental.”

All this is on Post’s mind as the car inches through the traffic toward the Washington suburbs. She’s back on the phone, checking in with a different Virginia candidate. “Thank you for putting your name on the ballot,” she says. “It’s the bravest thing you can do.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Philip Elliott at philip.elliott@time.com