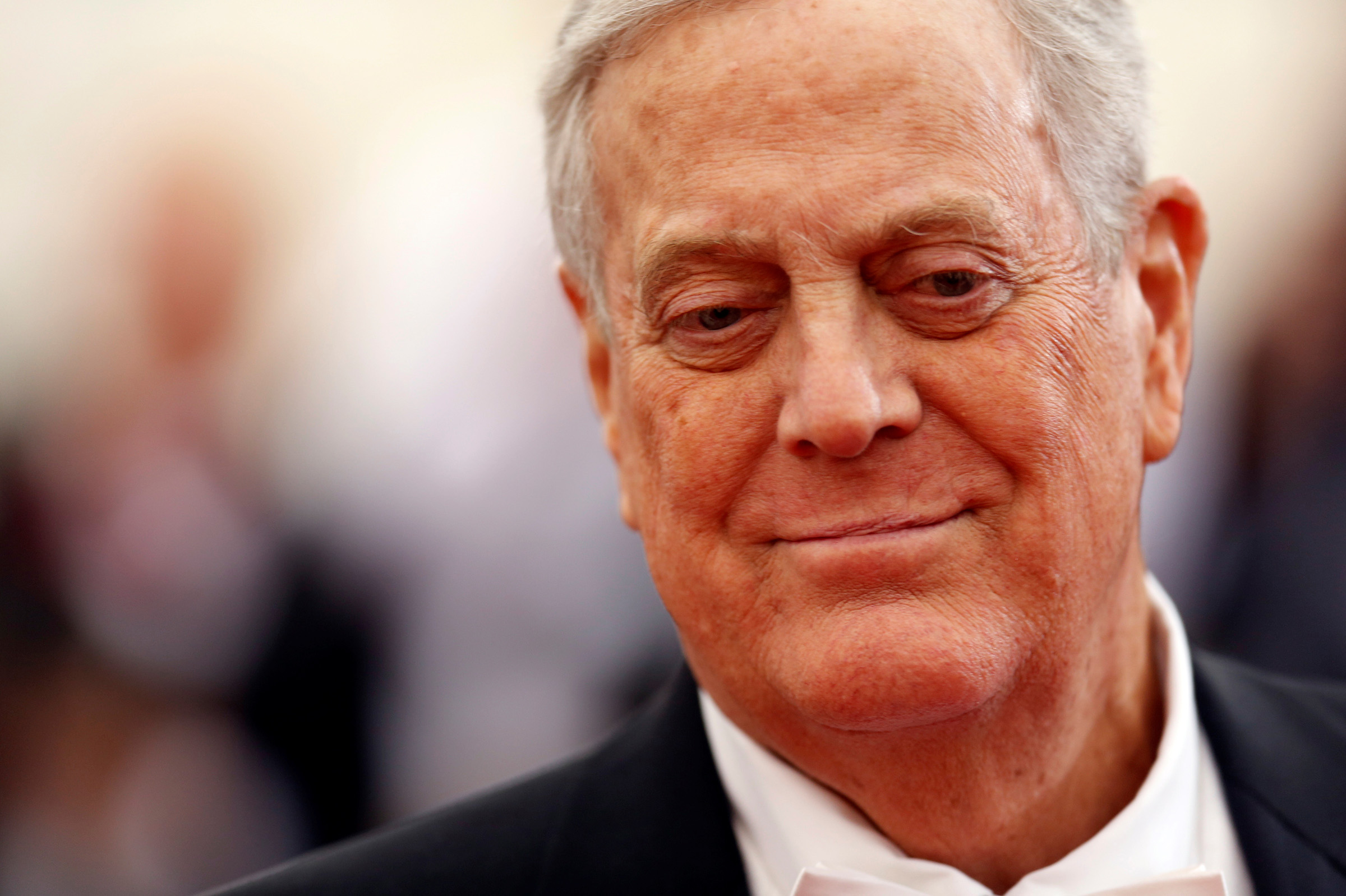

David Koch towered over most rooms, both physically and politically. He liked it that way.

At 6 feet, 5 inches tall, the professional contrarian and ideological warrior had little interest in blending in. Even as Democrats made him and his deep political giving a symbol of the corrupting influence of money on politics, he remained defiant and doubled-down. Koch could not be kowtowed into a crouch.

David Koch’s death was announced Friday. No cause was given, although his brother Charles noted in a statement that David had previously fought prostate cancer. He was 79.

In his youth, he resisted his wealthy family’s headquarters in Wichita, Kansas, and instead set up his own wing of the business in New York City. While his brother Charles Koch read economics at home in the heartland, David Koch entertained models at his Manhattan penthouse and became one of New York’s most generous patrons. As the 1970s came to their sputtering end, Koch stepped into politics for the only campaign of his life, buying his way onto the Libertarian Party’s ticket as its vice presidential nominee, attracting almost a million votes nationwide in a race that saw Ronald Reagan win the presidency.

When Bill Koch challenged sibling Charles’ spending on libertarian causes and staged a failed boardroom coup, David and Charles began a bitter and years-long battle against two other siblings to wrest control of the vast Koch Industries out of their hands. And as the nascent Tea Party movement started stirring in the late 2000s, it was David Koch who saw the potential to use his family’s already formidable network of deep-pocketed allies to tap into the nation’s frustrations through groups like Americans for Prosperity. In doing so, Koch became perhaps the most prominent and vilified symbol of the billionaires who have turned 21st century politics into a playground of the privileged.

Few individuals have enjoyed more of an influence of American politics than Koch, even though he never held public office in his life. He was a hard-edged ideologue who took once-fringe ideas of his father’s John Birch Society to the mainstream by dint of his checkbook and cold-eyed disdain of what he saw as limits to freedom. His critics say he and his family’s network of donors and groups coarsened politics during Barack Obama’s presidency to the point that rabble-rouser Donald Trump was able to win the Republican Party’s nomination in 2016, despite the fact both David and Charles both found Trump personally and politically abhorrent. Koch’s defenders note that he risked his reputation and privacy to become one of the most pilloried figures of an era to advance the causes he held dear.

Like all giants in a society, his legacy is unwieldy and full of contradictions that defy a simple reading. As a 42% stakeholder in the second largest privately held company in the country, Koch was said to have a net worth of around $50 billion, making him the 11th-richest person on the planet, according to Forbes’ billionaire index. But unlike others in his ranks, Koch had one of the freest wallets for charities of his choosing: his lifetime philanthropic giving topped $1 billion to causes such as the Smithsonian, Lincoln Center and cancer research. He patronized groups that preached civility even as he nudged his political arm to portray Obama as an existential threat to American capitalism. Such complications only made Koch that much more of an enigma, a role he hardly minded.

David Hamilton Koch was born in 1940, the son of a tough industrialist father who pitted his sons against each other to toughen them up. Their caretaker on the family ranch knew Koch’s temper so well that he kept leather boxing gloves at the ready for David and his twin brother, Bill, to settle disputes. Educated in chemical engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and a standout basketball star there, he would settle in New York and set up his own division, Koch Engineering, securing four patents. Whereas his brother, Charles, would be the strategic face of the company as its chairman and CEO, David would stay in New York as a man-about-town and the parent company’s executive vice president.

Koch was as, at his best, an affable elite who preferred dinners at his Manhattan homes, telling what today would be called “dad jokes”––even though he didn’t marry until he was age 56. He enjoyed the ballet and art, so much so that the New York City Ballet’s home and the plaza in front of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art both carry his name. A devoted free-market evangelist, he nonetheless kept tabs on his money; he wanted detailed reports on spending, demanded receipts and didn’t always pick up the dinner check. He also found government regulations overly restrictive and counter-productive, whether he was deriding environmental rules or bans of prostitution. He called them, during his 1980 run for vice president, “victimless-crime laws.”

But he also could be a reliable contrarian and bitter enemy. It was during that 1980 campaign that he showed a true disdain for the status quo because he could. He took advantage of a Federal Election Commission loophole that allowed candidates themselves to donate unlimited cash to campaigns and causes. When he pledged hundreds of thousands of dollars to the Libertarian Party’s ticket, he earned himself a spot on it, despite some activists’ questions about whether Koch was the best fit. He didn’t run to win. He ran to evangelize libertarian ideology.

At that very moment, David was still working diligently as Charles’ lieutenant, fending off a family clash over the business. Bill, David’s twin, had been raising concerns about Charles’ management, and he had his reasons. Koch Industries clashed with government officials at the Department of Labor, Department of Energy, the Internal Revenue Service, the Justice Department and the Bureau of Land Management. Criminal investigations were ongoing and some family members found Charles’ “market-based management” to be too clinical and autocratic. David sided with his brother, who was growing the company at remarkable rates. Years of infighting followed. Eventually, Bill and the fourth brother, Frederick, were excommunicated from the family business, sent away with $1.1 billion. They sued, but in 1998, a jury found they had not, in fact, been swindled. Three years later, David, Bill and Charles reconciled — and signed a private settlement, the terms of which are still secret.

David Koch never lost his political zeal, though. In Washington, he saw the profligate spending under President George W. Bush just as bad as over-regulation under President Bill Clinton, whose administration in the fall of 2000 unleashed a 97-count indictment of Koch Industries and its employees for environmental violations. (The company pleaded guilty to one count and paid a $20 million fine.) Koch thought Bush’s war in Iraq as misguided, but kept his counsel private lest he surrender his own privacy. He thought the deficit spending would lead to ruin.

But when Obama won the White House, David and Charles sprang to action. Over the years, they had amassed a network of libertarian donors who would also write checks to think tanks and universities that were working on Koch-aligned priorities. What if they could use that research, tap into the nascent Tea Party and build an army of grassroots activists to stop Obama?

They tested their theory. It worked. Obama’s fellow Democrats lost 63 seats in the House, Republicans’ best showing there since 1938. It cost the Koch network its privacy and millions, but it was worth it, David Koch felt, because he now had a check on Obama, and maybe a way out of his health care law. The partnership with the Tea Party-style activists wasn’t a neat fit ideologically, but it was part of a bigger pursuit that allowed Koch to have a greater sway in politics than he ever previously enjoyed. When someone from a Koch-aligned group called, lawmakers listened.

Koch loyalists then went about laying the groundwork for 2012. They went all-in on nominee Mitt Romney, a former Massachusetts governor and fellow capitalist evangelist. Romney, of course, lost. Koch strategists to this day have deep regrets about that choice and still can cite what they see as strategic errors from the campaign. Their total outlay for all activities, including social causes for the 2012 cycle? A cool $400 million.

David and Charles Koch in 2015 started down the pathway of picking a favorite for 2016. They told reporters they had prepared a total budget of $899 million to spend on politics and policy for the two-year election cycle but ultimately held fire after several contenders made the pilgrimage to meet with the brothers and their partners. When Trump won the nomination, it was official: they’d be working on state and local races, as well as killing projects like mass transit, which they argue is “a boondoggle.” Trump was not an ideological fit by any stretch and his style rubbed even the showiest of the Koch the wrong way. Trump, for his part, taunted them from afar.

At the same time, there was a sense inside the Koch orbit that pure, partisan politics was sliding from atop the list, despite a $400 million budget for the November 2018 elections. The Koch orbit worked against the White House on its hardline immigration plans and its ban on Muslims, and with it on tax cuts and a rewrite of the criminal justice laws. They anticipated early that 2018 would be brutal for Republicans.

David Koch stepped away from the company and from the political wing in 2018, Charles Koch announced in a memo to employees. David Koch had skipped recent political summits and a retirement had been in the offing. A non-specific health issue was to blame. All the while, politics continued to fade from the first items on the agendas distributed at donor summits.

The company David Koch leaves behind has more than 100,000 employees working in 60 countries, with revenues north of $100 billion. Perhaps more than that, though, is his network of likeminded patrons and its outsized potential to shape political forces. At its height, the Koch network had an almost billion-dollar footprint in the conservative movement, on par with the formal Republican Party. It’s not an exaggeration to say that Koch remade a large part of the GOP, even if its current leader is not of his style. But that’s the thing about revolutions: once begun, they’re tough to control.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Philip Elliott at philip.elliott@time.com