Mass demonstrations have pushed the Chinese-ruled territory of Hong Kong into its most serious crisis in decades. The international airport has been at a standstill since Monday, while an increasing number of shops have been shuttered and thoroughfares blockaded.

In 1997, Hong Kong returned to Chinese rule under a “one country, two systems” mode of governance, guaranteeing the city a high degree of autonomy, an independent judiciary and freedoms not allowed in mainland China. The fifty-year agreement is due to expire in 2047.

Nearly two million people have taken to the Hong Kong streets since June to protest a proposed extradition bill, which would have allowed suspected criminals to be sent to mainland China for trial. Critics have said it would threaten Hong Kong’s legal freedoms, and could be used to silence political dissidents.

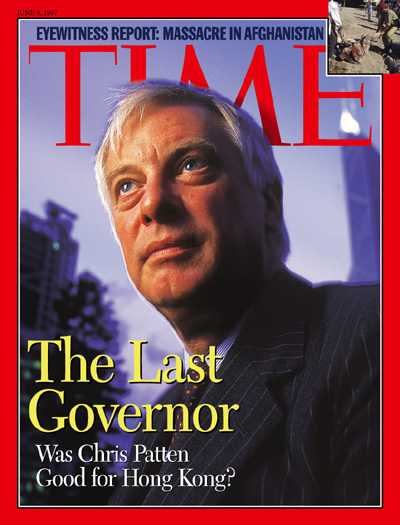

Hong Kong’s last British governor says protestors are up standing up for their freedoms, which have been “whittled” away under the Chinese President Xi Jinping. Chris Patten, a former Conservative Party minister who governed Hong Kong from 1992 to 1997, helped push through constitutional reforms in the final years of U.K. rule that were later dismantled by the Chinese government. Now retired from politics, he is Chancellor of Oxford University.

Patten spoke with TIME by phone on Aug. 7 about what’s at stake for Hong Kong and China as the unrest continues. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What is your sense of Hong Kong’s identity?

Most residents in Hong Kong are ethnically Chinese but have a strong sense of citizenship. That’s not surprising because it’s been a great international trading city, it has the rule of law, some fine universities, it did have a completely free press. It had all the freedoms associated with a plural and open society except the ability to elect its own government. That is what people regard as defining who they are. While they don’t deny their Chineseness, they do say that they’re Hong Kong Chinese.

How has China leveraged influence over Hong Kong?

For the first ten years after 1997, I think Hong Kong did pretty well. China by and large kept its side of the bargain on the “one country, two systems” agreement.

Things have changed since Xi Jinping came became President in 2013. I think that just as he’s cracked down on any sign of dissidence in mainland China, he’s been keen to exert greater control through the joint liaison office in Hong Kong and through United Front activists in Hong Kong. There’s been whittling away of free speech and the autonomy of universities, and an undermining of the rule of law.

It’s a terrible error for the Beijing authorities to have behaved in a way that makes people in Hong Kong fear the Chinese government. And it’s appallingly bad for China’s image. But for the last few years, the Chinese Communist Party hasn’t cared very much [about their image] as they’ve been tightening their control over everything. If China breaks its word over Hong Kong, how can you trust China anywhere else?

Why has there been such strong public opposition?

The extradition law built on people’s anxieties in Hong Kong because over the last few years they’ve gradually seen their freedoms whittled away. It would have knocked down, dismantled the firewall between the rule of law in Hong Kong, and put in laws that are determined by the Communist Party in mainland China.

But it was handled terribly by Hong Kong’s Chief Executive (Carrie Lam). After the first big demonstrations, the government didn’t back off, it didn’t bury the bill. Instead, officials said they were postponing the bill. They tried to find a way of appearing to back down without actually doing so. The second thing that has triggered the protests is the violent way that the demonstrations were handled.

How do you think the government will respond to continued protests?

I imagine that the Hong Kong government and the people who pull the strings in Beijing think that if they do nothing the fire will burn out – the demonstrations will stop – and they’ll use the courts to send as many to prison as possible.

I don’t think China will intervene militarily. That would bring back a lot of memories of Tiananmen and it would be extremely bad for China’s relations with other countries, and of course calamitous for Hong Kong.

If China can only accept the sovereignty of Hong Kong on the basis of sending in troops and tanks, it would be an appalling error.

China is a very powerful nation with no notion of the importance of human rights and the rule of law. When you see what’s happening in Xinjiang with the development of a totalitarian, surveillance state – it’s obviously a worry that China – a very important country in the world – doesn’t share the same view of human rights, due process and accountable government that the rest of us have.

What’s is the future of Hong Kong’s pro democracy movement?

Since almost two million people have protested against the extradition agreement, there is clearly a huge part of Hong Kong opinion that feels very strongly about these matters.

The government must begin a process of reconciliation. Before things get totally out of control, before someone gets killed or very badly injured, the officials need to find a way to talk to not just the demonstrators who they have accused of violence, but the overwhelming majority of people in Hong Kong.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Introducing the 2024 TIME100 Next

- The Reinvention of J.D. Vance

- How to Survive Election Season Without Losing Your Mind

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Scams

- Did the Pandemic Break Our Brains?

- The Many Lives of Jack Antonoff

- 33 True Crime Documentaries That Shaped the Genre

- Why Gut Health Issues Are More Common in Women

Contact us at letters@time.com