Fifty years ago, nearly half a million people convened at Max Yasgur‘s farm in Bethel, New York, for the first Woodstock Arts & Music Festival in August 1969. Billed as “An Aquarian Exposition: Three Days of Peace and Music,” the event featured now-iconic sets from acts like Jimi Hendrix, Santana and Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young. In an era before large-scale festivals were the norm and well before the advent of cell phones, the weekend was marked by issues with traffic, weather, overpopulation and under-preparation. But Woodstock is still considered one of the era’s most memorable and critical cultural junctures, an event that defined the spirit of a generation and would come to represent it.

TIME asked some of the photographers who documented that weekend of music, community and mayhem to tell us which of the images they made at the festival stick with them all these decades later. From the music to the human moments that endured, here’s what photographers Baron Wolman, Ron Frem, Barry Z. Levine, Elliott Landy and Burk Uzzle had to say about the indelible photos they captured during those three days. Above all, what stands out are the interactions between members of the crowd—people learning how to get by in subpar conditions, finding love and solidarity in a mass of humanity and exercising a newfound sense of freedom.

Baron Wolman, Getty Images contributor

All summer long, my friend, the acclaimed photographer Jim Marshall, and I had been shotgun riders as we traversed the country photographing a variety of music festivals. Woodstock trumped them all—there was no way to compare what we came upon that August weekend in Bethel to any other concert anywhere, ever. I was fascinated, captivated, enchanted and transfixed by the crowd, the hundreds of thousands of kind and gentle souls who made the trek to Yasgur’s farm. It was the people upon whom I focused my cameras. I wandered among them daily, taking pictures, building a personal diary of three miraculous days that I somehow knew were both a promise and an aberration.

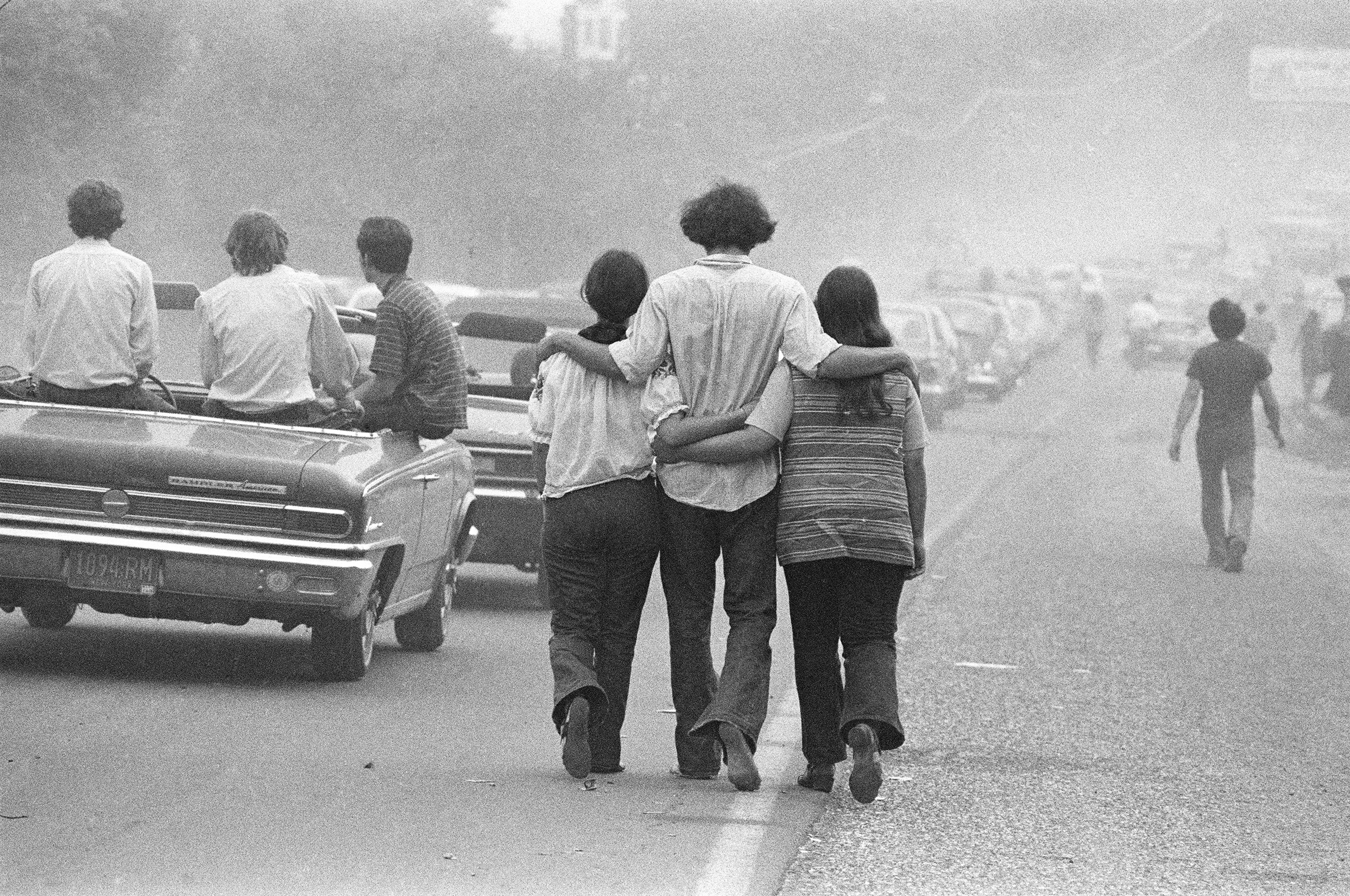

When I look at my photograph, “Walking to Woodstock,” I see young people walking together to follow a shared dream, together. It makes me think of Joni Mitchell’s poignant song, “Woodstock,” although she wasn’t even there:

I came upon a child of God

He was walking along the road

And I asked him, where are you going

And this he told me

I’m going on down to Yasgur’s farm

I’m going to join in a rock ‘n’ roll band

I’m going to camp out on the land

I’m going to try an’ get my soul free

We are stardust

We are golden

And we’ve got to get ourselves

Back to the garden

As I know firsthand, the traffic didn’t deter them, the long walk didn’t deter them, the weather didn’t deter them, the large crowd didn’t deter them… They were part of a loose-knit, and yet still identifiable, community from all over the country which believed in a world filled with Peace, Love and Music. Their dream came true, if only for three days, but it proved people CAN get along if they want to. Sadly, 50 years later, too many of us appear not to want that magical, mystical life of peace. Today, people too often illustrate that they prefer hate to love, violence to peace, and even their music reflects those attitudes—at times empty of hope for the future. And perhaps for good reason, as things are very different now.

Woodstock showed the world how things could have been, and for this reason it’s important that we never forget this experience, this place, this time, this dream that came true, if only for three days. Even then, we held out hope that the former would characterize our future lives. If only…

Ron Frem, AP contributor

Going to Woodstock seemed like a fun way to spend my day off. So my buddy Frank and I took off on what we thought would be a typical 1.5-hour drive upstate. Even though we were still many miles away, the roads were becoming jammed with vehicles of all types filled with concertgoers. Before long, all lanes were bogged down in one direction. When traffic slowed to a crawl, many chose to leave their cars parked along the side of the road and walk the rest of the way. Frank and I remained with our car hoping to get closer. After several hours of not making any forward progress and me needing to be ready for work the next day, we decided to abandon our mission. Our predicament was we were stuck with no way out, until thankfully by chance an ambulance with lights and siren was creating a path in the opposite direction. We made a u-turn and followed behind, finally getting a clear road home, disappointed that we couldn’t get to see any of the concert.

The next morning while preparing to head to the office for my regular day of assignments as a newly hired Associated Press staff photographer, I got a call from my editor with instructions to gather equipment needed to cover, of all things, the concert at Woodstock.

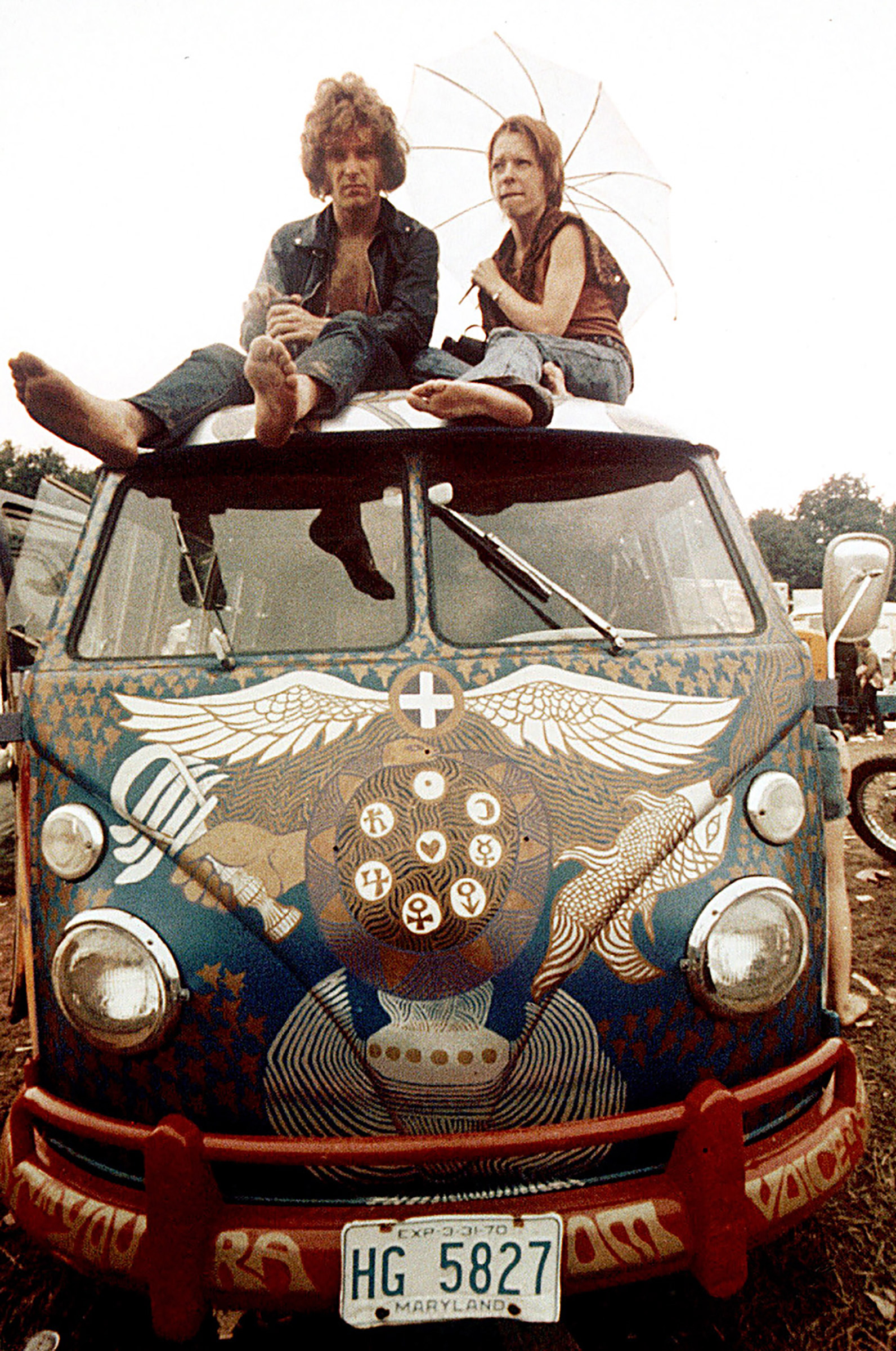

I told my editor of my experience from the day before and I didn’t think I would be able to get there by car. He said I would be going by helicopter and should prepare to stay for several days. The AP already had a remote set-up in a motel near the venue but the Albany crew, not expecting such a large event, was being overwhelmed and needed more supplies. I met fellow AP staff photographer Marty Lederhandler at our office in Rockefeller Plaza where we loaded up additional supplies including food and film and headed to the helicopter. At the site, I disembarked with the supplies and made my way to the motel while Marty flew overhead for aerial views and then headed back to the city. The motel was being used as a processing lab (way before computers and digital imaging) so my bed was the back of my colleague’s car. Being the rookie, I was assigned to walk up and down the roads looking for feature pictures to supplement the coverage while other photographers were covering the main entertainment. One of my favorite photos is of two “hippies” sitting on top of a decorated Volkswagen bus. I was able to restore the print from a damaged original transparency that had been lost for a long time before being discovered in the glove compartment of my vehicle (at that time, a later model Volkswagen bus). This image seems to reappear in print year after year for stories around the anniversary dates of the original 1969 Woodstock concert.

Barry Z. Levine, Getty Images contributor

Working as a writer/producer for Columbia Records in New York City, I heard about a big music festival in upstate New York and the rock stars that would be appearing—Janis, Jefferson Airplane, Jimi, The Who, Blood Sweat and Tears, Sly—and it sounded like hype. I drove up about a week before things were supposed to start and the first person I met was an old friend, Larry Johnson, who was working with Michael Wadleigh, the director of the soon-to-be documentary film Woodstock. I told him I had come up to take some photographs and he said they needed a still photographer for the crew—and then asked me if I would do it.

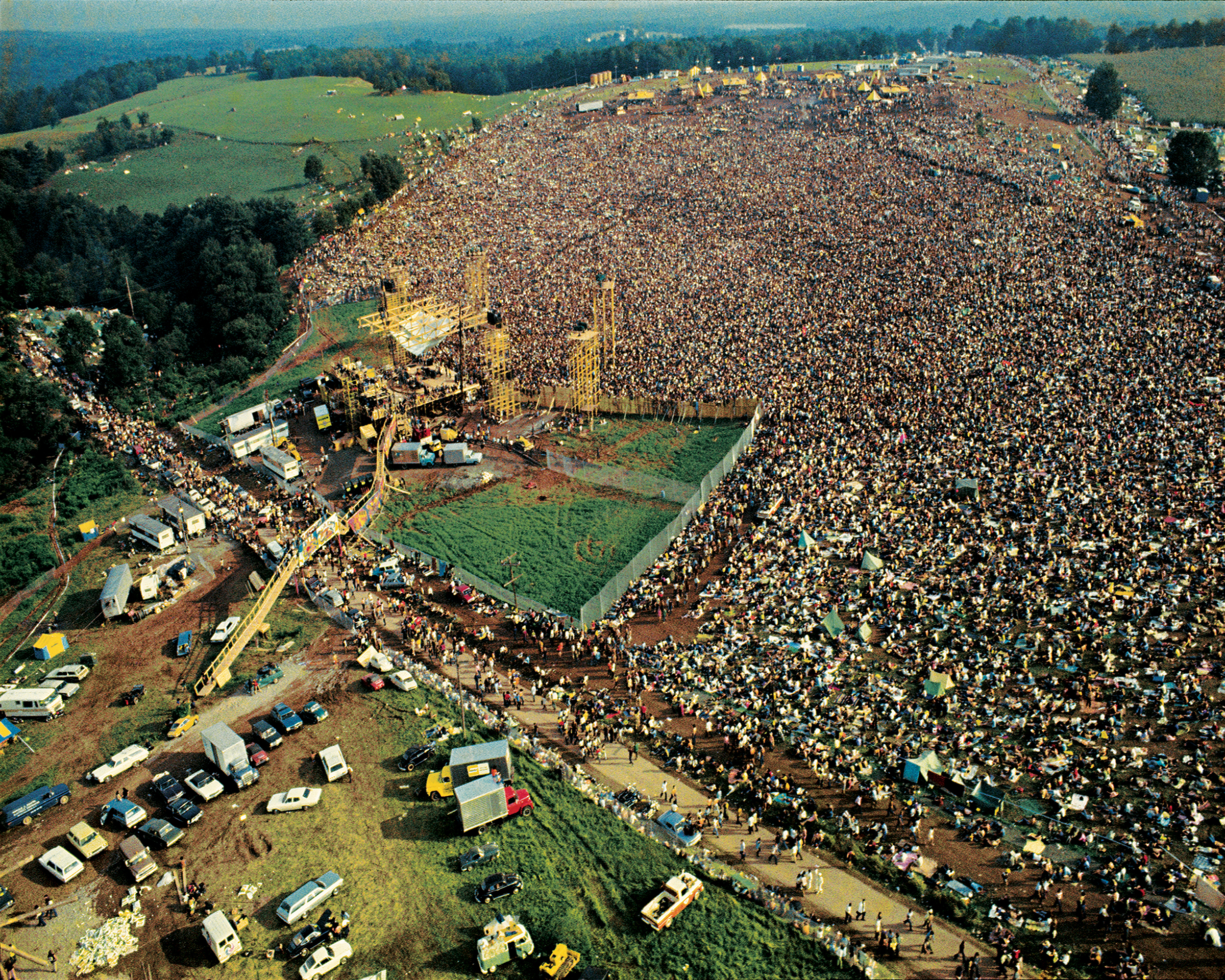

As part of the film crew, I had an all-access pass, which meant that I even got my own helicopter. Standing on the stage and looking out at the audience was impressive but seeing it from the air, as seen in this aerial shot, was a whole different experience. When we landed, we headed over to Filipini Pond. People were hanging around the edges, kind of wanting to go in, but needing someone to be the first. David and I dropped our clothes and ran in. That was all it took for the full-fledged skinny-dipping to begin.

And that’s what Woodstock symbolizes—freedom. Women and men. Naked. Without fear or shame. The freedom to do what we wanted to do. Without any need for “the authorities.” People saw a half-million others like themselves. Maybe in their hometowns they had felt like freaks—isolated and alone—but at Woodstock, they created a peaceful, loving, caring community.

For me, the audience—the crowd—was the real star of Woodstock. The feeling of togetherness was palpable. The feeling that everybody was in it together, and we were gonna make the best of it. Despite the crowds, the rain, the heat, the mud, the lack of bathrooms, food and water—there was not one assault, one robbery or one violent crime. It was the shared spirit, music and even the difficulties that brought everyone together. It was humanity at its best.

Elliott Landy, Getty Images contributor

Woodstock is a spiritual place and has a very special feeling about it, which is why I had moved there in 1968 and lived there on and off since then, before returning permanently in 1990. It’s where I was casually introduced to producer Mike Lang, who knew the photography work I’d done with Bob Dylan and the Band during my time in New York City. He called me up one day and asked to stop by, before asking me if I wanted to photograph the concert he was planning. I said sure and he told me he’d call me when he was ready, which is how I became what I like to call the official photographer of Woodstock.

When I think back, the experience of being there was truly one of freedom. You were free to think the way you wanted to think, rather than the way you were brought up to think, and that was extraordinary.

You were freed from concerns, from responsibilities. And you were stuck there—there was no chance you were gonna go anywhere or do something else, or call about your job, or anything like that. You were isolated, surrounded by an energy field. I think of brains as bioelectric devices and if you’re sensitive, you can feel it.

With half a million people there and everybody’s brain on the same vibration, it felt pretty good—It felt pretty calm to be in that crowd. There was just this sense of ease where you felt everything was going to be okay, no matter the conditions. There was also a sense of security and you knew you wouldn’t be arrested for smoking grass, or for taking your clothes off. Law enforcement was going to leave you alone.

That’s what this picture shows; that genuine sense of ease. It’s a close-up of just one group in the crowd, and although there’s no room to walk—you can’t even see the ground—everyone is tightly knit in a wonderful way. Although they’re crowded, they’re all comfortable in their own space.

When I look closer, I see that the young woman at the center is attractive, but she’s not objectified or sexualized in this situation. She’s free to be feminine without concern for its impact on anyone else, or fearful of whatever impact they might have on her. She’s probably stoned, grooving to the music, while contemplating something, and she’s almost caressing this blue balloon. It feels very feminine to me but also very childlike, which is how I feel Woodstock was overall.

That may actually be one of the most important “teachings” of the ’60s culture—the value of being childlike, being curious about everything and trusting of everything. These people are embracing their inner child in a beautiful way and these balloons highlight that experience. I don’t know why they had these balloons or where they got them, but it doesn’t matter. Even the young man in the yellow striped shirt, who is staring at his broken yellow balloon, is showing us something. He’s not upset, he’s just aware that change is always going to happen. Sometimes it’s good and sometimes it’s bad, we just have to learn how to live with it in a positive way.

Burk Uzzle

These beautiful people live on, decade after decade, and while showing us their love from within a muddy blanket, have created a legacy of hope for a better world. Tenderness vanquished mud and mire, and the poetry of the composition as they were lined up with the background mountain on a lovely, moody morning, has given us an image that has actually gotten more and more pungent over all the decades.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- How Elon Musk Became a Kingmaker

- The Power—And Limits—of Peer Support

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com