Teachers in two local districts within the El Paso, Texas, region spent Monday consoling stunned, grief-stricken students and figuring out how to help them make sense of the shocking attack by a gunman at a local Walmart on Saturday, killing 22.

Young children and teens in the Socorro and Clint Independent School Districts returned for their second week of school Monday in what was also their first time at school since the attack. Some were close enough to the shooting that they heard gunshots, according to a teacher. At one high school in Horizon City, which is part of the Clint district, students grieved a classmate lost in the tragedy.

For Jose Tobias, a high school math teacher at Horizon High School, Monday was spent mourning the loss of one of his own students. Among the 22 victims of Saturday’s massacre at the Cielo Vista Walmart in East El Paso was 15-year-old sophomore Javier Amir Rodriguez, who preferred to go by Amir.

“He was a very energetic kid,” Tobias tells TIME. “Talkative. I could relate a lot to him, to the way I was in high school.”

Tobias taught Amir freshman algebra 1. Tobias describes Amir as smart, popular and someone who loved to play soccer.

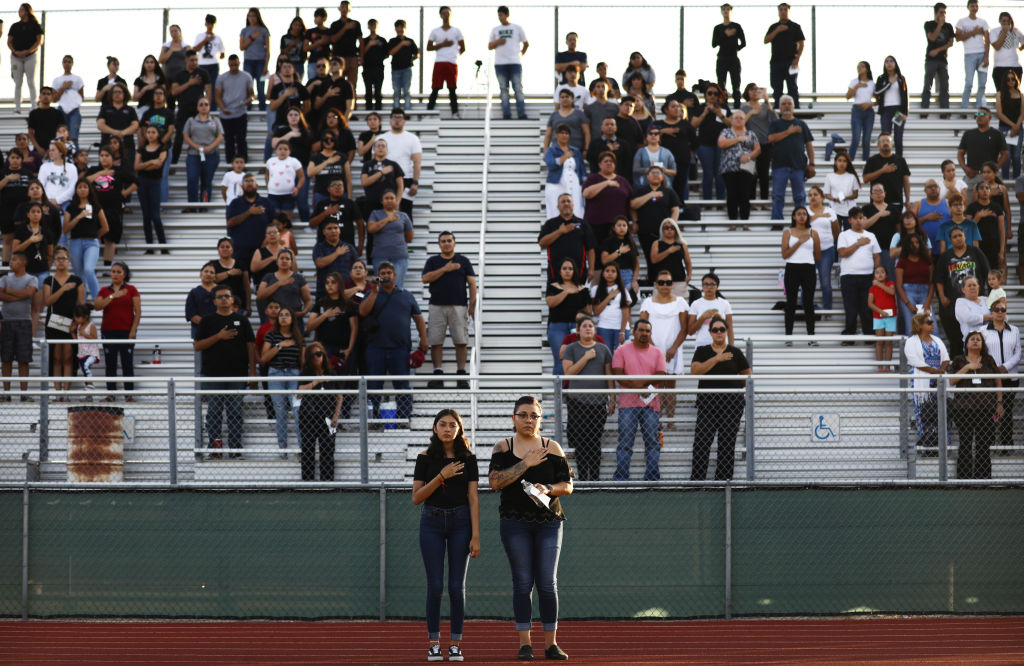

A vigil to honor Amir took place Monday evening at the Horizon High School football field. “He did have a lot of friends here,” Tobias says. “Some of the students are scared … they knew of these things happening, but someplace else, they never thought it would happen here.”

“We are deeply saddened and heartbroken over the loss of one of our own Horizon HS students, Javier Amir Rodriguez, a victim of the horrific tragedy that occurred in El Paso on August 3, 2019. Our heartfelt condolences and prayers are with his parents and family,” said Laura Cade, director of public relations at Clint Independent School District (CISD) in a statement to TIME.

Tobias says more security guards and counselors were sent to the school on Monday, and counselors spoke directly with friends of Amir.

Tammi Mackeben, director of school counseling for the Socorro Independent School District (SISD), says her first thought when she saw news of the attack was for the safety of the community. “Then, secondly, was making sure that we prepared to help our students and our families on Monday.” She thought of students and their families, “to make sure they felt safe, and secure, and knowing that they have someone to talk to.”

The school district increased security and had counselors meet with each classroom to check on students. Teachers were given tips on how to spot signs of trauma and grief, and were also offered their own mental health services.

Similarly, the El Paso Independent School District, which starts classes next week, says it is doubling “efforts to assess the physical and mental wellbeing of our employees. We know that in order for our teachers to help students, they need to assess their own level of grief and stress.”

“We are certain that the normalcy of school will provide much-needed relief for students and employees, and our resources will help those [who] will need it the most,” an EPISD spokesperson said in a statement to TIME. “El Paso and EPISD are resilient places, and our students and teachers will come together to grieve and push forward.”

Marilyn Aleman, who teaches yearbook and graphic design at Franklin High School, which is part of EPISD, says she’s preparing herself for difficult conversations ahead of their school year beginning next Monday. Some of her students have parents who are Mexican nationals.

“I have students that go to Juárez on the weekend” she tells TIME, referring to the Mexican city south of El Paso. “These kids are going to feel like they’re being targeted because of who they are but they shouldn’t. When they come into my room, I want them to feel welcome.”

A school in mourning

Tobias says Horizon High School felt quiet and somber on Monday — and he noticed a few students crying.

Tobias first found out that Amir had been missing through Facebook posts by fellow teachers. By Monday morning, it was confirmed that Amir was among the 22 killed by a gunman who has been identified as Patrick Crusius, a young white man from a suburb of Dallas.

“I started crying and I started shaking,” Tobias says about when he found out that Amir was a victim. “I couldn’t believe it. He was a good kid. You just get so attached to these kids. You see these kids and learn their personal lives almost every day for a whole year. Most of the time these kids come to us with their problems, they look up to us, and we get attached to them.”

“He was just a kid, he had his whole life ahead of him,” Tobias adds. “It hurts.”

‘They’re so little and they’re so innocent’

Immediately after Caitlyn Bowen learned of the shooting on Saturday, she began to think of her students — 22 fourth graders at Chester E. Jordan Elementary School in El Paso’s Far East Side. She worried about whether any of her students had been at the Cielo Vista Walmart where the shooting took place.

“Coming to work, I could just feel it,” Bowen tells TIME of arriving at school Monday morning. “You could see, something was off. I didn’t feel it really until my kids came in … One of my girls was crying and that’s when it hit me. So yeah, I’m a little shaky right now.”

Bowen has been a teacher for three years, and has never encountered a situation like this, she says. That morning, Bowen decided to open her classroom up to questions and answer them as honestly as she could.

“At first they were a little afraid to ask,” she says. “Even after answering, I got the same questions — Why? Who is he? They just didn’t understand.”

At one point, Bowen says she found herself unable to answer.

” ‘Are they going to be putting more cops around?’ ” Bowen says one of her students asked. “That was kind of like, honestly, I don’t know. Are they going to be doing more things to protect us around the city? I just told them, ‘No, we’re just gonna go about like normal’ — but no, it’s not, we’re not, none of us feel normal.”

Then, Bowen says she told her students about the support El Paso has been receiving from all corners of the country.

“I didn’t want to say anything that would scare them more,” she says. Because the school is located close to the Fort Bliss Army Base, Bowen’s students have a diverse mix of backgrounds, but are still predominantly Hispanic, she says. “I did let them know he was here to hurt Hispanics … I know they know that, but I don’t think they realize that he was specifically here for us.”

“These guys are so little,” Bowen adds. “Just this morning they were saying things, and they kind of laugh about it — they didn’t know how serious it is because they’re so little and they’re so innocent. I think the high schoolers are going to have a harder time.”

Feeling that their voice is not being heard

Montwood High School, part of the Socorro Independent School District, held a vigil on Monday morning, which graphic design and commercial photography teacher Justin Stene tells TIME was an emotional event.

“The atmosphere was very somber, very sad, but I would say that everybody was together,” he says. “It’s one of those moments that I will never forget. The whole school just came together… Everybody had arms around each other. There were students crying, there was faculty crying, you could tell the emotions were very high.”

Stene, who teaches ninth through twelfth grades and also teaches the school’s yearbook class, decided to reach out to his yearbook students the day before school via a group chat.

“Some of them were telling me in the group chat that they were afraid to come to school,” Stene says. “So of course I was thinking about reassuring them that they’re safe, reassuring them that I’m here for them, that if they need somebody to talk to, of course I will either be there for them to talk to them or to refer them to a counselor.”

For Stene, hearing his students’ concerns was the most important thing.

“A lot of these students are feeling that their voice is not being heard,” he says. “They don’t feel like El Paso will be listened to by Texas legislatures because we’re in such a red state … Some of the things that I’m reminding them is they’re the future generation. I’m reminding them that they are going to be the policy change-makers, that if they’re going through something right now they need to step up and be the voices in the community.”

— Additional reporting by Sanya Mansoor

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Jasmine Aguilera at jasmine.aguilera@time.com