Overfishing, hunting and land development have pushed more species closer to extinction, according to a new report.

The Red List report by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) found that 27% of the more than 105,000 species the organization has analyzed are at risk of extinction, a total of 28,338 different species.

IUCN also found that no species on its list have shown any sign of improvement since it was last updated in December 2018.

“Things are not getting better, they are getting worse,” Craig Hilton-Taylor, head of the IUCN Red List unit, tells TIME.

The Red List places the 105,732 species of plants and animals that it analyses into different categories: the number of species that are considered threatened fall into the categories of vulnerable, endangered and critically endangered. However, there are an additional 6,435 species that fall into the near-threatened category.

The endangerment of species is not only a critical issue for animal and plant life but can also have a detrimental impact for humans. “The future of humanity — food, fresh water, drinking water, clean air — is all dependent on maintaining the biodiversity around us,” Hilton-Taylor says. “We can’t afford to lose any of these species.”

Hilton-Taylor says that while updating the the Red List, scientists usually find species that can be removed from a high risk category because of conservation efforts — but this time around, species have either maintained their status or have moved into a higher risk category. This appears to demonstrate that current conservation efforts are not enough to stem the level of destruction.

“The numbers are just horrendous, that’s totally frightening,” Lee Hannah, a climate change biologist at Conservation International, tells TIME. “We’ve had a lot of great progress, we’ve got national parks, community conservancies, a lot of great conservation going on around the world, and these numbers tell us that it’s just not enough.”

Particularly threatened are species of Rhino Rays that have been overfished, in part for shark fin soup, a speciality in China and parts of Asia. There are also seven species of primates that have been hunted almost into extinction for bushmeat, and freshwater fish in Japan and Mexico that have declined in population because of pollution, invasive species and loss of free flowing rivers. Even deep-sea species are at risk because of deep-fishing and the oil and gas industries, according to IUCN.

The Red List update comes about two months after a grim report from the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) found that 1 million species of plants and animals are now threatened with extinction.

“This Red List update confirms the findings of the recent IPBES Global Biodiversity Assessment: nature is declining at rates unprecedented in human history,” said Jane Smart, Global Director of the IUCN Biodiversity Conservation Group, in a public statement. “Decisive action is needed at scale to halt this decline.”

Here’s what we know about the species that are at risk.

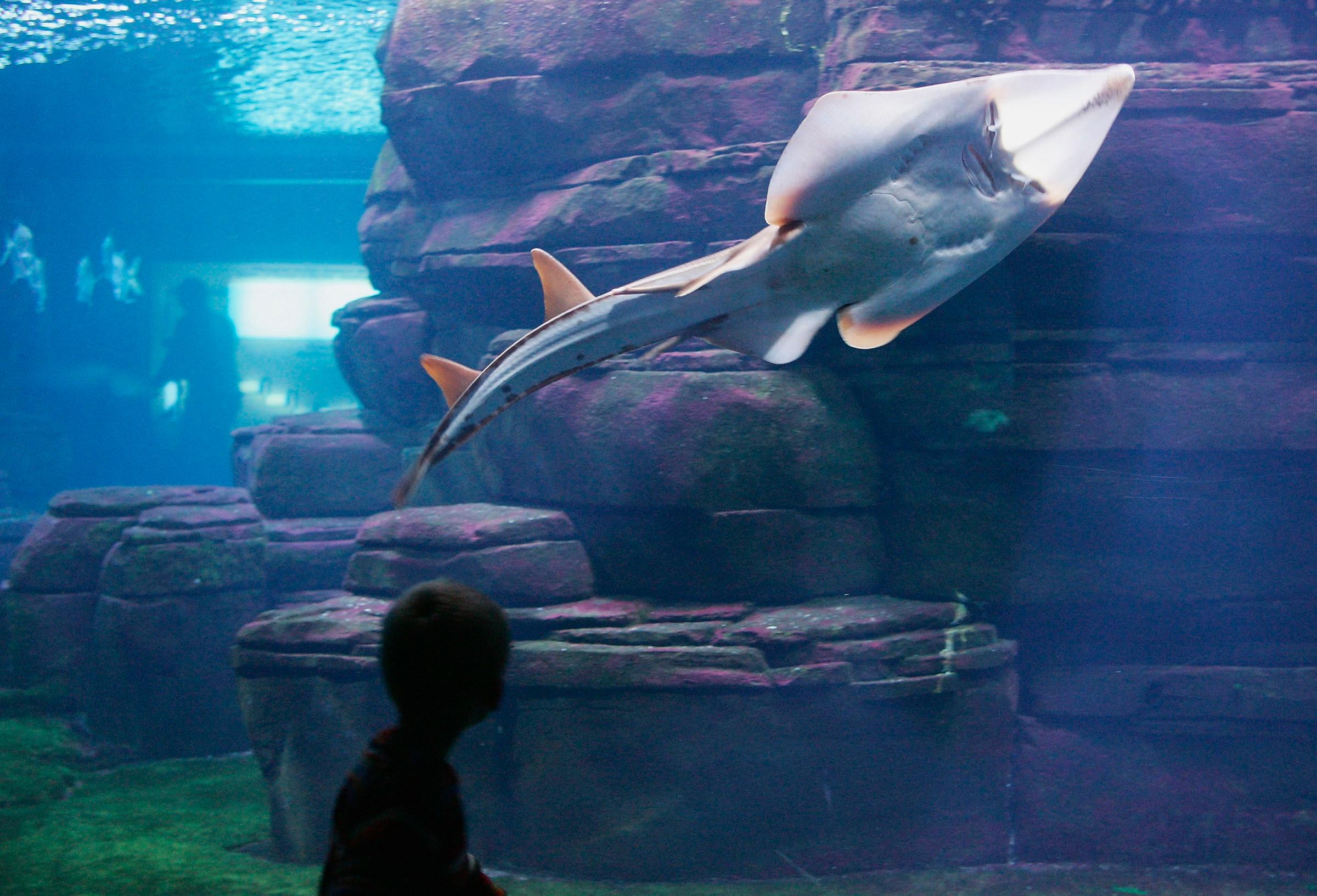

Rhino Rays pushed to critically endangered

Wedgefishes and giant guitarfishes that are collectively known as Rhino Rays are now the most endangered marine fish families in the world, according to IUCN. Fifteen Rhino Ray species were added to the Red List’s critically endangered category, only one category away from extinct in the wild. In total, 16 species of Rhino Rays were assessed. One type of Rhino Ray, the Shark Ray, has declined in population by 80% over the last 40 years.

IUCN says Rhino Ray meat is sold locally, and fins are cut to sell internationally for shark fin soup, but most are caught with other fish during unregulated coastal fishing. Unregulated and illegal fishing is a global-scale issue that has effected several fish populations as the global demand for seafood rises.

“We really have to up our game because we have numbers of species from sharks to rays that are headed toward extinction from fishery,” Hannah says. “We know that we’ve been late to the game to get marine protected areas and other conservation measures in place in the marine realm.”

Rhino Ray species can be found from the Indian and West Pacific Oceans and the East Atlantic Ocean and Mediterranean Sea. According to the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), they have low reproductive rates, making them more vulnerable to extinction.

Seven primate species are closer to extinction

Hunting for bushmeat and deforestation have pushed a decline in the primate population. In West and Central Africa, 40% of primate species are at risk of extinction, according to IUCN.

In West Africa, the roloway monkey has also moved into the critically endangered category. IUCN reports that there may be fewer than 2,000 roloway monkeys in the wild due to hunting for their meat and skin. The red-capped mangabey monkey is now also endangered.

Russ Mittermeier, chair of the IUCN Species Survival Commission Primate Specialist Group, urged creating new protective areas in West Africa, better management of already existing protective areas and establishing primate-watching ecotourism that has become popular in other parts of the continent, among other suggestions.

Freshwater fish in Japan and Mexico

A third of freshwater fish in Mexico and over half of Japan’s freshwater fish are in danger of extinction after loss of free flowing rivers and agricultural and urban pollution, according to IUCN.

“People often disregard wetland habitats,” Hilton-Taylor says. “People think they need to restore wetlands to something that’s better than a wetland, but then you wipe out all the natural biodiversity that’s there, including fish.”

But likely hundreds of millions of people around the world depend on freshwater fish as their main source of protein, according to Jeff Opperman, global lead scientist for freshwater at WWF, adding that people eat 13 million tons of freshwater fish per year.

There has been an 83% decline in freshwater species more generally since the 1970s, according to the Living Planet Index.

“That’s something that’s largely unknown by the general population,” Opperman tells TIME. “When people think about the extinction crisis in nature, they often think about coral reefs or tropical rainforests, but it’s the freshwater systems that are actually seeing the largest declines and I think that’s really in large part because freshwater species and freshwater ecosystems are literally below the surface.”

Dams, levees and other human constructions that interrupt river flow play a large part in the decline of freshwater fish populations, Opperman says. “The reproduction, the migration [of freshwater fish] is often triggered by changes in the flow. And so when that is changed, that can also affect them.”

What can be done?

Some of the world’s largest conservation groups are calling for 30% of land and 30% of ocean be preserved as protected areas by 2030.

“We know that the best way to protect species is to get habitat conserved,” Hannah says. “Freshwater is by far the most critical, terrestrial — on land — and we need to be doing this before the window closes in the next 10 or 20 years … It’s ambitious, but if we want to prevent these extinctions, that’s the sort of number we’ve gotta shoot for.”

Opperman says companies and the agriculture industry play a large part in the health of rivers and lakes around the world and urges consumers to support businesses that have sustainable business plans. “These major systems, and therefore consumer choices, are things that have among the strongest impacts on the health of rivers and lakes,” he says.

“We know with the right efforts, we can turn things around,” Hilton-Taylor adds.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- 22 Essential Works of Indigenous Cinema

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Write to Jasmine Aguilera at jasmine.aguilera@time.com