Three years after 49 people were shot and killed at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando, efforts headed by the OnePULSE Foundation are underway to build a memorial and museum to commemorate the victims. But the plan has been met with criticism by some parents of the victims, survivors of the shooting and local lawmakers concerned that the foundation behind the plan could be profiting off the massacre’s aftermath. Those concerned are requesting an audit of the foundation.

In a statement to TIME, Rep. Stephanie Murphy, D-Fla., a co-sponsor of the proposed legislation marking Pulse as a memorial space (and whose district includes much of Downtown Orlando), said that the foundation should welcome any protocol “that increases transparency and accountability to the public.”

OnePULSE became an official nonprofit in late 2016 to begin efforts to build a memorial and museum dedicated to those who were killed. One of the founding members, Barbara Poma, also owns the Pulse nightclub, and declined to sell it to the city. Board members, volunteers and advisors include Mayra Alvear, the mother of a victim, and Lance Bass of the boy band NSYNC. The foundation plans to build a memorial at the site of the June 12, 2016 attack, and a museum intended to be a “dignified place for remembrance, education, inspiration, and hope,” according to its website. Both are intended to open in 2022. The foundation also plans to build a “Survivor’s Walk” at the site, which will follow some of the paths that many of the survivors took to get to safety the night of the shooting. A temporary memorial already exists at the site.

How to best memorialize the sites of mass shootings (or move past the infamy thereof) in the United States remains a thorny issue. In Colorado, Jefferson County Public Schools Superintendent Jason Glass recently asked the local community to consider a potential proposal to tear down Columbine High School; in Newtown, Conn., Sandy Hook Elementary School was demolished in 2013, less than a year after the murders of 20 students and 6 educators — a new school was later rebuilt on the site. In Aurora, Colo. the Century Aurora movie theater reopened six months after a gunman killed 12 moviegoers.

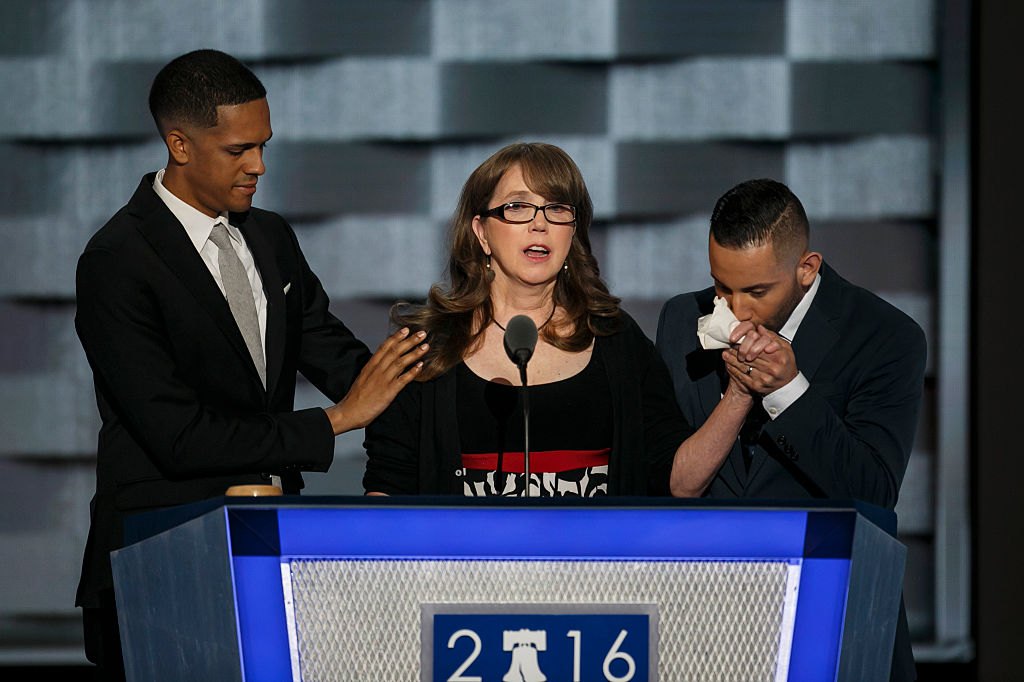

At a Monday morning news conference about the plans for the memorial and museum, Christine Leinonen, whose son Christopher “Drew” Leinonen died during the shooting on June 12, 2016, was removed from the event after interrupting and shouting at onePULSE Foundation CEO and Executive Director Barbara Poma, who owns the nightclub.

Leinonen is accusing Poma of profiting off the death of her son, and has been vocal about her requests for an in-depth audit of the foundation. “My son is earning zero now, while Barbara Poma is earning an executive salary year after year after year on my son’s death,” Leinonen tells TIME. According to the most recent tax information available, the only paid employee on the foundation’s roster is Poma, who reported a salary of $43,269 in 2017. (Leah Shepherd, the OnePULSE Chief Operating Officer, tells TIME there are now four paid staff members.) The foundation, which was established in 2016, also reported $893,910 in revenue and $921,181 in total expenses in 2018.

Norman Casiano, 29, who survived the June 12 shooting, said he shares some of Leinonen’s concerns. “The feelings that she has are feelings my family and I have been feeling,” Casiano tells TIME. “It’s hard to see people monopolize a situation like this and grow a name for themselves out of this after such a terrible thing.”

But Brett Rigas, 34, who also survived the shooting, said that onePULSE has always been a source of help — be that financially, advocacy, and in terms of growing a support network for those connected to the shooting. Rigas says that the foundation regularly corresponds with survivors, via newsletters, a private Facebook group, and monthly in-person meetings.

The onePULSE foundation says an audit is already underway to examine the 2018 fiscal year, and has been in the works since January 2019 by auditing firm Holland & Reilly, which Shepherd says will be an extensive breakdown of each cost by the foundation. “The audit will cover everything,” she says. “This is a four to five month audit that is completely thorough on every bank statement, every expense and every single income, every donation that’s coming to the foundation.” She adds the foundation will undergo an audit every year, which will be made available on the foundation’s website.

Leinonen says a general audit won’t be enough to make her feel assured that money isn’t being mismanaged.

At the Monday press conference, the foundation and local lawmakers announced Orange County, Fla., would allocate $10 million from its hotel tax to help fund the museum portion of the project, and that the Florida State Legislature is working on allocating an additional $500,000.

“It’s three years now that she’s collecting money,” Leinonen says. “And still she wants the tax payers to fund the memorial that she has been collecting money for for three years.”

Shepherd says the OnePULSE foundation is following the same business model at the 9/11 Memorial & Museum in New York City and the Oklahoma City National Memorial & Museum, which are public and private partnerships funded by the government and individual donors.

A spokesperson for onePULSE tells TIME that the hotel tax funds would not be handed over to the foundation in a lump sum. Instead, it could receive up to $10 million in contracts. The spokesperson also says that the $500,000, which is awaiting approval by Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, would go towards construction and administrative costs. DeSantis is facing his own controversy for not initially mentioning the LGBT community in a proclamation to commemorate the nightclub shooting.

“The leadership and staff of the onePULSE Foundation take their mission and work very seriously, and any statement that the foundation has not been transparent with our finances and the work involved in fulfilling our mission is misguided,” said Earl Crittenden, Board Chairman of onePULSE Foundation, in a statement to TIME. “We also want to emphasize that if a member of the public, a family member, survivor, or public official has questions about our finances, they are welcome to contact us. To date no member of the public has contacted our leadership about this issue.”

A parent and survivor’s concerns

“Orlando is the world of Disneyland and everyone has this perception that there’s such a thing as a happy ending,” Leinonen says. “There’s no fairy tale, it’s a horror movie. There will never be a happy ending for the Chris Leinonen team.”

Leinonen lost Christopher, her only child, at the nightclub when mass shooter Omar Mateen opened fired, killing 49 and injuring 53 others. Christopher’s boyfriend, Juan Ramon Guerrero, was also among those killed. One of the survivors is Casiano, who was shot twice in his lower back. He was 26 at the time. “I had my career going, I was making money and I was on my own two feet,” he says. “Now I receive disability.”

Casiano says he has permanent nerve damage and experiences pain regularly, or loses feeling in his lower body. But he is used to the pain — it’s his mental health that plagues him the most. Two of Casiano’s close friends didn’t survive the attack.

Both Casiano and Leinonen have discussed their feelings about the onePULSE memorial together, and found a lot of common ground, though Casiano says he doesn’t harbor any negative feelings toward Poma.

“Them doing all these fundraisers and receiving all this money from all these different types of sources does make it seem like it is being mishandled,” Casiano says. “And we’re not at the receiving end of this help. They continue to say that they’re raising money for this, they’re raising money for that, but the survivors and the families who lost people there, they’re still grasping for air trying to make it back to where they were prior to Pulse.”

Leinonen, an attorney and former state trooper, says she harbors a lot of anger, including towards Poma, who she feels should have provided proper security at the nightclub. She is part of a group of 129 survivors and family members of dead loved ones who are suing Barbara Poma and her husband Rosario, as co-owners of Pulse, alleging they did not provide proper security at the nightclub.

Orlando police Officer Adam Gruler, who was off-duty and working a shift as a security guard, was armed and the only security on duty the night of the shooting. He fired at Mateen, but did not pursue him into the club.

In a statement to Orlando Weekly shortly after the suit was filed in 2018, Poma said “What is important to Rosario and me is that we continue to focus on remembering the 49 angels that were taken, the affected survivors and to continue to help our community heal.” As of June 2019, the Orlando Sentinel also reports she had labeled the suit “frivolous.” (On this matter, neither Poma nor onePULSE representatives responded to a request for comment from TIME prior to publication.)

“The bottom line is we think the Pomas are just trying to dump liability here,” Keith Altman, a lawyer representing the 129 plaintiffs tells TIME. “On the one hand, she talks in support of the victims, on the other hand she’s profiting from it, and on the third hand she’s trying to keep the assets and not accept responsibility.”

“What I am upset about is that Barbara Poma gets to make all of the decisions,” Leinonen says. “What I want is a democracy. For the families of those affected and the survivors to vote on how to handle this tragedy. We are the Pulse tragedy, not the nightclub owner.” onePULSE’s Leah Shepherd says the families, survivors and first responders have always been a part of the foundation’s process, and have been a part of every decision made. She says the current interim memorial was built based on feedback by those impacted the night of the shooting and that the foundation hosts a family day twice a year, offering updates on the foundation’s progress.

“They come first in everything we do,” Shepherd tells TIME. “Ms. Leinonen has been invited to have a seat at the table at every single thing that we do.”

“I have so much respect for that woman,” adds Brett Rigas. “I don’t know how she sleeps, she does so much.”

“There needs to be something to make sure this isn’t forgotten,” Rigas continues. “Even yesterday, the mayor talked about how there are little kids in the city who don’t know what happened. There needs to be something to make sure that what happened to us isn’t forgotten after we’re gone.”

Lawmakers who support an audit

Three federal lawmakers, Stephanie Murphy, D-Fla. Darren Soto, D-Fla. and Val Demings, D-Fla. have sponsored legislation to designate Pulse as a national memorial. On Wednesday, Demings tweeted that she hoped Poma’s “vision for a Memorial allow us to remember the past and provide hope for the future.”

Murphy also agrees with auditing the foundation, though. “Like any other nonprofit, the OnePULSE foundation should undergo regular, independent audits so that the families of the victims can have confidence in their work and their mission,” she said in an email to TIME. “The foundation will have an important role to play in keeping the memory of the victims alive, and for that reason they should welcome any action that increases transparency and accountability to the public.”

Several other state lawmakers have been vocal supporters of Leinonen and have called for an audit of the foundation. In the comments of a post Leinonen made on Facebook calling for an audit, Representative Carlos Guillermo Smith, D-District 49, wrote, “I think based on the amount of taxpayer money the OnePULSE Foundation has received from state and county funds, they should be required to go through an independent audit. That would expose any misspending or it would give the public confidence in the financial stewardship of the organization.”

The Sentinel reported that state Rep. Anna Eskamani, D-District 47, had similar views. With these types of public dollars being spent, and because this was such a uniquely tragic event for our community, there has to be an audit. And it has to be external,” Eskamani told the newspaper. And I say this not from place of malcontent, but just because of the need for transparency, especially when you have so many families impacted.”

“The mission of the OnePULSE Foundation is to tell the story on behalf of the families and the survivors and the first responders,” Crittenden tells TIME. “But then there’s confusion, as we have said, as to what our mission is, and we’re focused solely on scholarships and building the museum — the national museum— and the memorial. Because we have to keep telling the story and make sure that this doesn’t happen again.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Jasmine Aguilera at jasmine.aguilera@time.com