Before gunfire tore through a crowd of concertgoers at the Route 91 Harvest country-music festival in Las Vegas on Oct. 1, 2017, Jonathan Smith was not scared of guns. As bullets rained down around him, the father of three raced toward danger, lifting strangers who had fallen to the ground and rousing others who were too frozen in fear to run.

But then he was shot. Around him, 58 people were killed and almost 500 were wounded in the deadliest mass shooting in modern U.S. history. Smith survived, but the 32-year-old from California, who still has a bullet lodged in his neck, now trembles when he hears anything that resembles the sound of gunshots, like fireworks or even helicopters.

“I kind of shut down a little bit,” he says. “Once you have something piercing through your skin and you can smell it burning, then you’ll know what fear feels like.”

Smith is not alone in his fears. Today, 59% of Americans say random acts of violence like mass shootings committed by Americans in the U.S. pose the biggest safety threat to them, compared to 16% who fear terrorism attacks by foreigners on U.S. soil and 25% who fear attacks by religious extremists on U.S. soil, according to a Reuters/Ipsos poll conducted after 31 people died in back-to-back shootings in El Paso, Texas and Dayton, Ohio. The poll also found that 78% of Americans believe another such attack will likely unfold in the next three months, with 49% of those respondents considering it highly likely. Another recent poll indicated one-third of U.S. adults are so stressed by the prospect of mass shootings that they avoid visiting certain places or attending certain events.

So far this year, there have been more than 250 mass shootings, according to the Gun Violence Archive, a widely cited nonprofit that counts incidents in which at least four people other than the shooter were injured or killed.

In the wake of the massacres in Texas and Ohio, Amnesty International, the human rights group, warned travelers to “exercise caution” when visiting the U.S. due to its gun violence problem. “A guarantee of not being shot is impossible,” said Ernest Coverson, an Amnesty campaign manager. Japan, Venezuela and Uruguay have also issued similar travel advisories following the shootings.

With more than 265 million civilian-owned guns in circulation in America, should you be afraid of them? It’s hard to say, since the question is so broad, the phobia so personal and the topic so polarizing. Studies on this issue have also been scarce since Congress voted in 1996 to limit the scope of research into gun deaths and injuries by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

"A guarantee of not being shot is impossible."

Statistically, the average American has a greater risk of dying from heart disease or cancer than from a firearm, according to the National Safety Council. Car crashes also kill about the same number of people in the U.S. as guns do each year, CDC statistics show. In 2017, firearms killed 39,773 people and traffic deaths killed 38,659; in 2016, firearms killed 38,658 and traffic deaths totaled 38,748. Other figures also paint a stark reality of the uniquely American threat. People in the U.S. are 25 times more likely to die from gun homicide than people in other wealthy countries, a 2016 study in the American Journal of Medicine found. In 2017, the most recent year with available data, nearly 40,000 people in the U.S. died from firearm injuries, more than eight times the number of U.S. military members who died overseas during Operation Iraqi Freedom between 2003 and 2010. Most of the U.S. gun deaths in 2017 were suicides, but statistics show that if someone is murdered in the U.S., there’s a high probability it will be with a gun. According to an FBI breakdown of homicides, more than 70% of murder victims were killed by firearms in 2017.

To some extent, the answer of whether you should be afraid of guns may depend on whom you ask. In TIME’s Nov. 5, 2018 cover issue on guns in America, which featured perspectives of 245 people, many firearm owners said they felt safer with a gun and believed people would be less afraid if they became more familiar with them. A 2017 Gallup poll that measured Americans’ anxiety levels after the Las Vegas massacre also found gun owners were significantly less worried about mass shootings.

Criminologists and other experts who study U.S. violence say the fear of guns may be more warranted in certain parts of the country, specifically low-income areas within cities. According to the CDC, about 14,500 Americans were murdered with guns in 2017. More than half were young black men killed in metro areas, which has been the pattern for at least the last five years, data shows. “Firearm violence and firearm injuries take different forms, depending on where you live, your gender, your race and ethnicity and your age,” says Phoenix-based criminologist Jesenia Pizarro, who is studying firearm injuries and deaths among children and teens as part of a National Institutes of Health-funded research consortium. “If you’re a racial minority who lives in an inner city that has a high crime rate,” she adds, “then the levels of fear are more heightened, and the actual data would support that it is something you should actually be concerned about.”

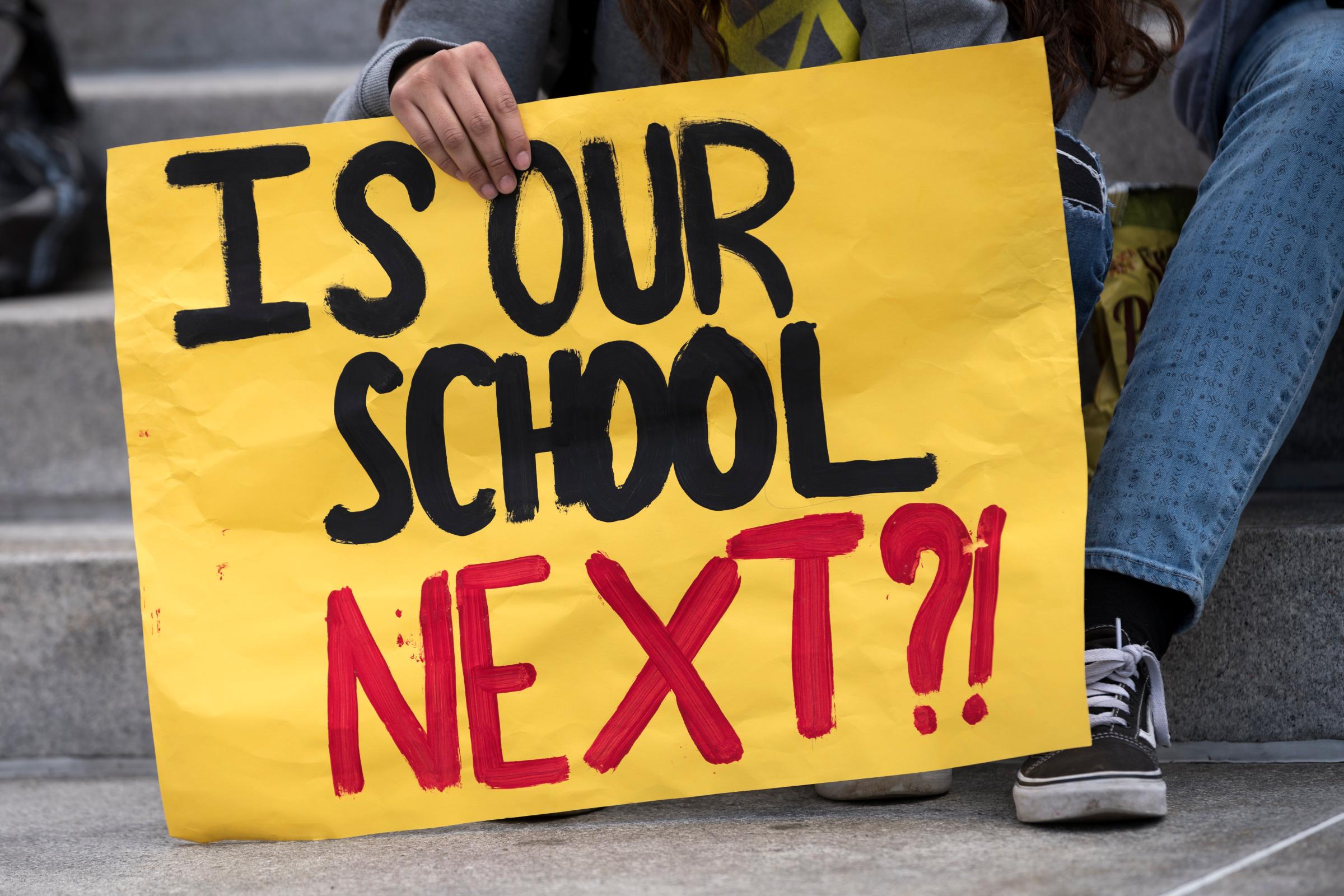

From a psychological standpoint, experts say it’s easy to develop a fear of guns when mass shootings are carried out in what should be safe spaces, like schools and places of worship—and seemingly often. On June 17, 2015, nine black worshippers were killed inside the Mother Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, South Carolina. Two years later, at the First Baptist Church in Sutherland Springs, Texas, a gunman killed 26 congregants, including a pregnant woman, her unborn child and a toddler who was wrapped in her dying father’s arms. Seventeen students and teachers were fatally shot on Feb. 14, 2018 at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Fla., which was once named the safest city in the state. Later that year, 10 students and teachers were gunned down at Santa Fe High School in Texas.

“People overestimate how likely it is to happen to them because they can easily think of an example,” says social psychologist Frank McAndrew. “When they think of how likely am I to be killed in a mass shooting, they can think of all the examples of mass shootings they’ve seen in the news.”

The day-to-day probability of being involved in a random high-casualty attack in public is still low, McAndrew says. The fear of guns, he adds, is perhaps misdirected when statistics show Americans have a higher chance of harming themselves intentionally or loved ones accidentally at home from firearms.

“There is reason to be afraid,” McAndrew says, “but the most common kinds of things that kill people are the ones that everybody believes isn’t going to happen to them.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com