Homes make a city. More than buildings, roads, schools, markets, hospitals and shops, it’s homes and the people who live in them that create the life of a place. The Islamic State of Iraq and Syria conquered Raqqa, which it named its first capital, and eventually the Iraqi city of Mosul, where it declared its caliphate, in order to control millions of those lives. Between these twin capitals, ISIS militants ruled with a level of cruelty and madness almost unknown in our time.

It took a year of sustained combat to pry the two cities from their grasp. In addition to marshaling thousands of Iraqi Army and Syrian rebel ground troops, the U.S.-led coalition embarked on a relentless campaign of airstrikes to dislodge the ISIS fighters. In the process, nearly all of the city of Raqqa and the Old City of Mosul were destroyed. More than a year later, they remain in ruins, and the possibility that they will be rebuilt remains in doubt.

Between October 2016 and October 2017 — from the beginning of the campaign for Mosul until the end of that for Raqqa — the U.S.-led coalition dropped 46,683 air-released munitions in Iraq and Syria. According to Airwars, a U.K.-based organization that tracks airstrikes and civilian casualties, the U.S. military fired 29,000 munitions — including bombs and land-fired rockets and artillery — in support of Iraqi security forces in Mosul. Between airstrikes and artillery barrages, the U.S. launched an estimated 20,000 munitions into Raqqa during the operation there.

American military commanders reached back into history for parallels to the scope and ferocity of the battles. They said the fight for Mosul was the largest military operation in the world since the invasion of Iraq in 2003, that it was the heaviest urban combat since World War II, and that the destruction resembled Dresden. Secretary of Defense James Mattis characterized the fight as “a war of annihilation.”

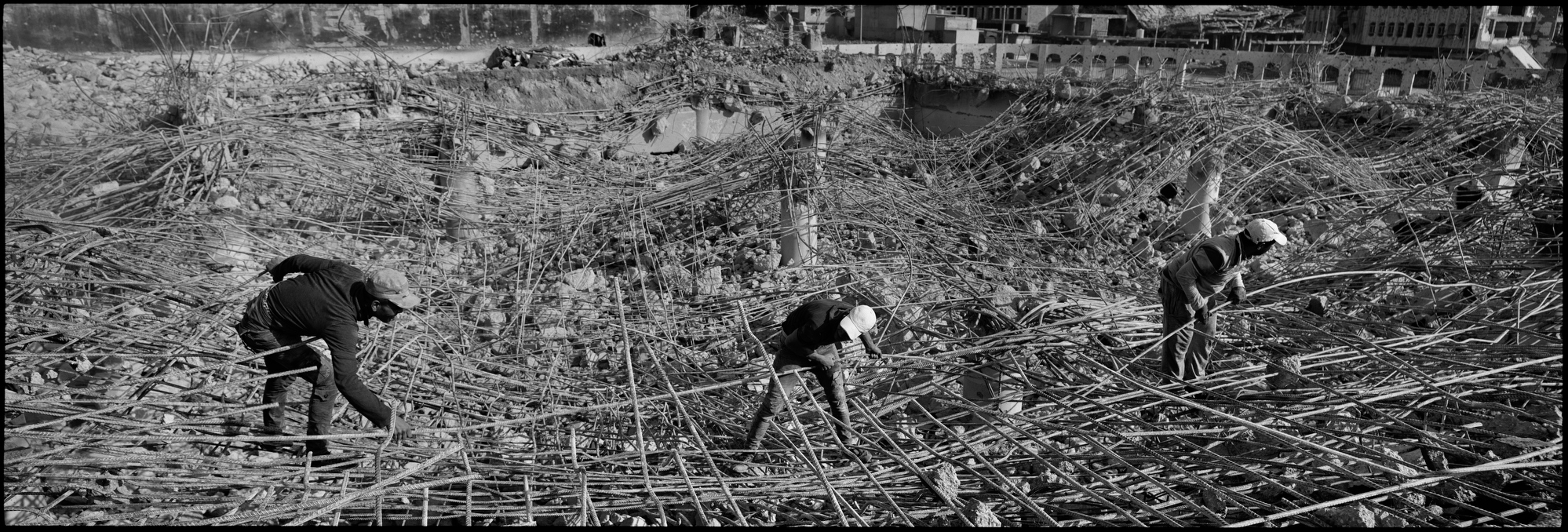

The destruction is near total. The United Nations calculates that 80 percent of the Old City of Mosul is in ruins, with 8,000 homes damaged or destroyed. The fighting left behind eight million tons of debris. Raqqa is considered “unfit for human habitation,” with 11,000 buildings damaged or destroyed, around 70 percent of the city. The consequences for residents are worse.

The relentless bombing campaign, the long duration of the battles and the lack of an independent, on-the-ground investigation make an accurate accounting difficult to gather. Current body counts are almost certainly too low. Thousands have been recorded but hundreds more bodies are believed to remain buried in the rubble. The wreckage of both cities is littered with leftover IEDs and unburied corpses.

Looking across the Tigris, toward the Maidan, the riverfront neighborhood in west Mosul, the ruins of ancient homes stick up like broken teeth against the sky. Here along the banks, trucks from the Old City dump loads of debris, mountains of it. You notice the marble everywhere; once gleaming architectural details intricately carved generations ago now lay discarded, pulverized.

Walking slowly along the mounds reveals an archaeology of oblivion. The detritus of daily life mixed with the castoffs of war — ammunition and unexploded ordnance, toys, cooking pots, kevlar vests and flowered blankets — all tossed with human remains. Hands, legs, teeth, ribs and scalps surface disarticulated, desiccated, never to be buried or identified.

The disorienting experience of walking through Raqqa challenges your visual perception. Nearly every building in sight is damaged or destroyed. Holes as big as a stove punch through the roofs. Cinder block, tile, furniture, their insides spill outside.

Everywhere you turn the view is pocked by tall buildings reduced to rubble and columns, without walls or windows or doors. Floors flattened onto floors below. Some buildings stand, still, groaning as they struggle to remain upright. It taxes the imagination to visualize the amount of explosive power needed to destroy so many buildings.

In both cities, residents have slowly, fitfully returned to try and carve a new path out of the wreckage. In the Old City of Mosul, falafel stores powered by generators sit on the ground floors of buildings pancaked above them. In Raqqa, apartment blocks half destroyed by airstrikes are half occupied in the areas untouched by them.

The power is on, and water is back to most of the neighborhoods. But local governments scramble desperately to introduce a measure of normalcy. The debris is mostly cleared from the roads, but the progress more or less stops there.

Mosul and Raqqa — distinct cities with different histories, peoples and dynamics — share a difficult prognosis: there seems today little chance they will be restored to their pre-ISIS states, much less with help from the U.S. In March 2018, the Trump administration froze funding for stabilization programs in Syria — money that would have helped rebuild Raqqa, pay for demining and shore up the fledgling Civil Council.

According to Leila Mustafa, head of the council, the rebuilding costs alone are $800 million. Iraqis estimate the cost to rebuild the Old City of Mosul could be as high as $7 billion. There, corruption and incompetence impede progress and the U.S. has committed only a few million dollars for assistance and little coordination.

Caught between the brutal rule of the Islamic State and the “annihilation tactics” of the coalition campaign, the people of Raqqa and Mosul struggle to remake the homes they lost.

More than 18 months after ISIS was driven out, the life of these places remains frozen in time — at a moment just after the last bombs fell, the fires went out, and the U.S.-led coalition declared victory and moved on.

An exhibition of this project, titled “Cities in Dust,” is on view at The Bronx Documentary Center in New York City from April 4-21, 2019.

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox