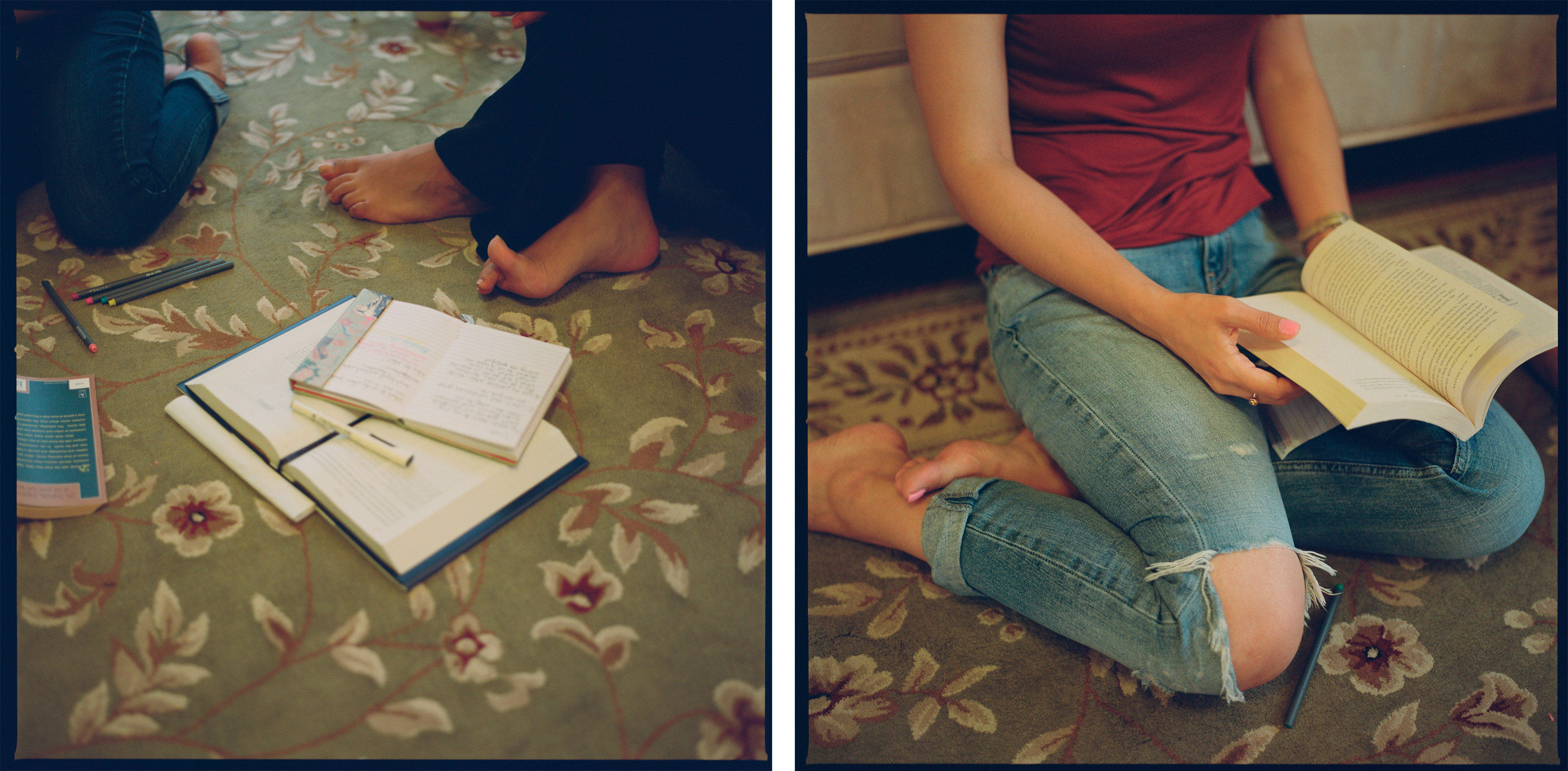

A few minutes past 3 p.m., after Henna Qureshi and Adeela Khan take a moment to pray, they settle on a living room rug with two more friends to talk. It’s a drizzly July afternoon, and Qureshi, Khan and Freshta Mohammad have gathered in Nafisa Isa’s family home in Ashburn, Va., for their monthly halaqa, an Islamic study group. Isa tucks her feet beneath her knees as she spreads colored pens across the floor for all to share. The topic of the day is “Nice for What?” — title inspired by the Drake song — a theme that women of all backgrounds can relate to.

“As ambitious Muslim women, we have to hold ourselves to high standards of conduct in our lives — whether it’s in the workplace or in community settings — prioritizing being kind, helpful and compassionate above all else,” Isa begins, reading the prompt they’ve each pondered in preparation for this meeting. “How do we react when people aren’t kind to us? How do we assert ourselves and express our emotions in a way that doesn’t stifle us or contradict our values?”

The four women, along with a few other friends, been meeting regularly since 2016, when Isa decided to create a dedicated setting for her peers to discuss Islam and their experiences as Muslim American women. There are halaqa groups across the country, but theirs is uniquely Millennial, Isa says — while they study the Quran, they also draw upon pop culture for discussion topics and add activities like visiting museums and crafting to their agendas. “We have these conversations about faith, personal growth, philosophy, theology, all the stuff that you would expect,” Isa says. “But then we’ll also paint unicorns.”

The women, all northern Virginia residents, come from diverse backgrounds and lead vastly different lives outside of the group. Isa, 31, born in Bangladesh and raised in Columbia, S.C., is a program manager at the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center. Qureshi, 34, grew up in a Pakistani family in Bradford, Pa., and is a pediatrician. Mohammad, 33, a chief of staff at a consulting firm, was born in Afghanistan. Khan, a 33-year old Pakistani American grew up outside Rochester, N.Y., and now works for a healthcare nonprofit. “We’re creating sisterhood and a soulful space where we can be vulnerable with each other, where we can express our emotions and be honest about how we’re feeling,” Isa says. “This group helps all of us deal with these broader issues of prejudice and violence.”

Isa, Qureshi, Khan and Mohammad say they need the supportive outlet they’ve built together more than ever before. This is a room where they can talk about the ways that prejudice looms in a political moment that has enabled, and at times even encouraged, expression of hate against immigrants and people of color. Isa has been called everything from “Osama’s niece” to a “terrorist.”

In their regular meetings, all four share stories of being stereotyped or forced into prescribed boxes, both by members of their own communities and people outside of them. Khan struggled with racism growing up in a predominantly white community. Qureshi, who felt pressure from members of the Pakistani American community to be married at a younger age, now has a husband who does half the housework, which “confuses” the older generation. Mohammad is sometimes met with surprise when she’s assertive, or even just present, in the workplace. “The prophet’s wife was a businesswoman — one of the wealthiest in the region,” she says.

Each has her own way of finding her place in a culture loaded with misunderstandings about South Asians, Muslims and women — and together, they make a point to consider the vast range of experiences within Muslim Americans in all their diversity, recognizing that their point of view is limited. “A lot of people have a misconception that Muslim women don’t have their own minds, that they’re submissive people, or that they’re the exact opposite, where they’re ultra feminine,” says Khan. “We’re not a monolithic group.”

Isa starts the “Nice for What” halaqa discussion with an anecdote of her own — recently, a woman spoke to her aggressively and Isa wasn’t sure how to respond. Qureshi offers wisdom gleaned from her daily experiences in her medical practice, where she sometimes works with patients who are emotionally distressed and behave abusively. “It can be a lesson, just being able to say, ‘I under what you’re saying, but I can’t really hear you when you’re using that tone,’” she says.

“What I struggle with, though, is feeling like I don’t stand up for myself,” Isa continues. It’s a constant internal battle, given that Islam calls for its followers to greet others with peace, while those who practice it in the U.S. aren’t always given that benefit. “It feels like an analogy for how I relate to things that are going on in the world, too, because I’m like, ‘Why can’t I do more?’”

Mohammad nods and adds, “We’re a lot harder on ourselves than other people are.”

The group speaks about the pressure they’ve each felt to represent Muslim women — that feeling of needing to set a “good” example (a virtually impossible task on its own, given the world’s subjective views of how women “should” be). Mohammad describes how her name is taken as a face-value signifier of her religion, and how people sometimes interpret that signifier as an invitation to ask her questions about “all Muslims.” “Well, there’s a lot of cultural diversity,” she says. “I’m just telling you my version.” Khan nods and adds, “I just want to be me.”

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision