Toward the end of the 2015–2016 ski season, I was on a competitive high. I had come back from multiple crashes in 2013 and 2014 that left me with a swath of injuries, particularly to my knees, and I was winning race after race. Everything was going so well that with a few weeks still left, I’d already compiled enough points to win the season-long downhill title, and I was on pace to win the overall title as well.

Then my great run came to an end. I crashed in Andorra, a tiny principality in the Pyrenees. It had snowed a ton the night before the super G, and I was maybe six gates from the finish when I got caught in some soft snow and leaned in. I hyperextended my knee, causing it to lock up. It wasn’t a dramatic crash—I didn’t flip, I didn’t catch any air. It was just one of those occasions where we shouldn’t have been racing until they’d had a chance to clear some of the snow.

The medical facilities in Andorra were fairly limited, and the doctor didn’t have access to an MRI, so when it came to a diagnosis, we had to wing it. The X-ray looked O.K., and the ligaments checked out fine, so I figured it was just a bruise. There was a super G combined scheduled for the following morning, so I said, “I think I can ski.”

Read More: Lindsey Vonn Is the First American Woman to Win an Olympic Gold Medal in Downhill Skiing

But later that night, my knee got super swollen, so we drained two vials of fluid from it. The next morning, it got so big during my warm-up that we needed to drain it again. Normally, when you pull fluid out of your knee, it’s this yellowish color. But if you fracture your bone, it bleeds. What we pulled out was bloody, which meant something was broken that hadn’t shown up on the X-ray.

The morning of the race, by the time we finished draining my knee, it was just in time for me to say, “Let’s do it.” I almost missed my inspection and had to call the International Ski Federation official and plead with them not to close it. But I made it in, I raced, and I won the super G portion.

In between runs, one of my competitors complained in an interview, “Lindsey’s so dramatic. She always has something wrong with her. She’s constantly saying something is injured, but she’s obviously faking it, because she keeps winning.” In the moment, her words pissed me off, but they didn’t surprise me. I’d become used to hearing a version of this over the last couple seasons.

Ever since I’d returned from my knee injuries, competitors or people in the media wouldn’t believe that I was hurt or in pain and would accuse me of pretending I was injured to add drama to my run or heighten TV interest. I wish it could go without saying, but I would never do that. I didn’t want to be injured in the first place, and even when I was, my preference was for nobody else to know. In fact, there were plenty of times I was injured and went out of my way to try to keep the problem under wraps. You want your competitors to think you’re stronger than you are, not vulnerable. So I skied through injuries that might have ended other people’s seasons, but I kept it to myself. Was it always the smartest decision? Maybe not. But it was my choice.

I’ve always believed that in an individual sport like skiing, it should be up to the athlete whether they want to compete. When it came to injuries, there was some testing to make sure you were all right to ski, especially where concussions were concerned, but if you sandbagged the test—intentionally doing less than your best—it was easy to pass. The protocols are stricter in a sport like football because there’s more money at stake. If a skier gets a concussion, no one is going to get sued over it. In skiing, it all comes down to what an athlete is willing to risk—it’s never the coach or the doctor who is putting their life on the line, it’s you. So you need to make that decision for yourself.

Of course, there were plenty of times that keeping word of my injuries out of the press was impossible. And that’s when my private choice about whether to push through an injury became a public spectacle—something that none of the skiers, myself included, wanted to deal with. The problem for me was that usually, once I’d set my mind on a goal, I didn’t see quitting as an option. I wouldn’t deliberately do anything to hurt myself or blatantly go against my doctor’s advice. But after a couple of years of fending off injuries, it got to the point where I’d proven everyone wrong enough times that even my doctors would say, “I don’t know, Lindsey, what do you think? Do you think you can ski on it?”

At different points in my career, some of the other athletes didn’t like me, but I never felt that the dislike was about who I am as a person. Instead, I think a lot of it was due to all the hoopla that was created around me—all this drama built up around my injuries and my recoveries and my performance—attention I never sought that nonetheless became a part of my narrative. Understandably, the other girls on the team got sick of answering questions about me. “How is Lindsey?” “Is Lindsey racing?” “What is Lindsey up to?” “Is Lindsey hurt?”

I felt misunderstood at many points throughout my career. Amid all the accusations of “Lindsey’s dramatic, Lindsey’s flamboyant, Lindsey’s just doing this for attention,” I would think: Can I just be who I am? Did anyone truly believe I would go off and say, “Oh, let me fake this tibial plateau fracture”? I didn’t choose to have injuries and comebacks. I don’t like drama. All I ever wanted was to focus on skiing. I would trade all the attention my injuries brought me for a healthy pair of knees.

The truth is, your competitors don’t have to like you, but that accusation of being “dramatic” touches a nerve in part because it’s just not a word that gets thrown at men in the same way. I always suspected that if I were a man, my injuries would have been covered for what they were, rather than for the distraction they caused.

And if I had been a man, and behaved the same way and achieved the same things, everyone would have believed me when it came to my injuries. They would have taken me at my word instead of second-guessing me or accusing me of faking it. If a man had come back from some of my injuries, everyone—the press, fellow athletes—would have been like, “Wow, that’s f–king gnarly. Respect.” Instead of doubting my honesty, they would have celebrated my grit. When it came to people’s expectations around toughness and resilience, there was definitely a double standard that wasn’t in my favor. One of the hardest things is to fight like hell through a lot of pain to compete, only to have people tell you they don’t believe you’re hurting.

I’d be lying if I said I didn’t wish the drama and doubt weren’t part of my story at the time it was all unfolding. But just as I learned from every mistake I made on the slopes, I also learned from these experiences. At a certain point I stopped letting the skeptics and the naysayers bother me so much. That’s not to say I became completely immune—I’m still human—but I found power in this: I know the truth about what I’ve been through, and the only person I can control is myself.

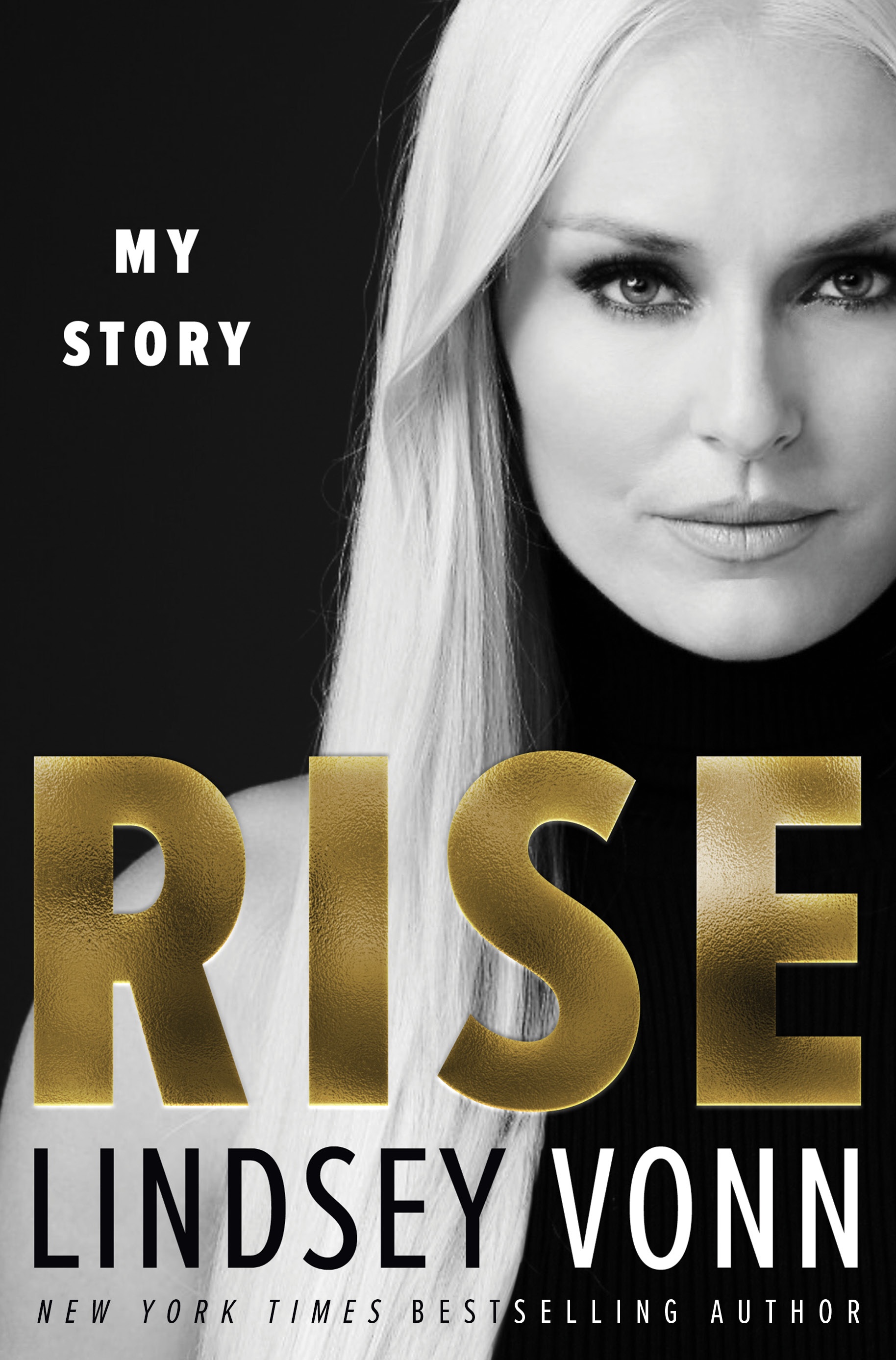

Adapted from Rise by Lindsey Vonn Copyright © 2022 by Downhill Gold, Inc. Reprinted by permission of Dey Street Books, an imprint of William Morrow/HarperCollins Publishers.

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness