On Dec. 15, 2014, I began my tenure as the 19th Surgeon General of the U.S. I expected that my focus as the “nation’s doctor” would encompass issues like obesity, tobacco-related disease, mental health and vaccine—preventable illness. But as I embarked on a listening tour of the U.S., one topic kept coming up. It wasn’t a frontline complaint. It wasn’t even identified directly as a health ailment. It was loneliness, and it ran like a dark thread through many of the more obvious issues people brought to my attention, like addiction, violence, anxiety and depression. It wasn’t always easy to tease out cause and effect—in some cases, loneliness was driving health problems; in others, it was a consequence of the illness and hardships that people were experiencing—but clearly there was something about our disconnection from one another that was making people’s lives worse than they had to be.

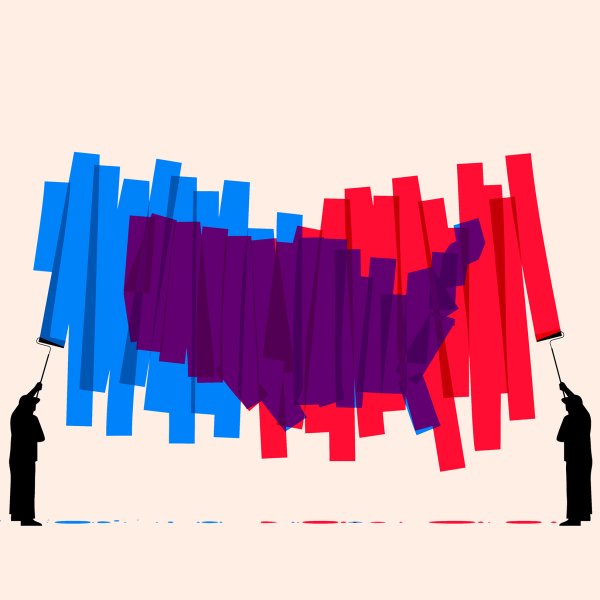

At a time when we’re being instructed not to leave home or visit loved ones, loneliness may seem like a given, but even before most people knew what “social distancing” was, the pervasiveness of this feeling was apparent. While the experience of loneliness is as old as humanity, recent years, marked by a politicized climate of distrust and division, have felt like an inflection point. Communities are dealing with pressing problems—like climate change, terrorism, poverty, and racial and economic inequities—that require dialogue and cooperation. But even as we live with increasing diversity, it’s easier than ever to restrict our contact, both online and off, to people who resemble us in appearance, views and interests, and dismiss those who don’t share our beliefs or affiliations. The result is a spiral of disconnection that’s contributing to the unraveling of civil society today.

Part of the issue is that we don’t necessarily encounter those who are different from us in our daily lives: according to the Pew Research Center, 68% of suburbanites are white, compared with just 44% of city dwellers. That sets up a racial disconnect between suburban and urban populations. Even in urban centers, people often live in neighborhoods that are segregated by race or socio-economic status. Meanwhile, millions of Americans in cities, suburbia and rural areas alike are struggling with poverty and without good-paying jobs. This has steeped fear and resentment not only among those who feel they’ve lost status they’re entitled to, but also among those who feel they’ve been too long excluded from their fair share. In 2018, one major poll found that 79% of U.S. adults are concerned that the “negative tone and lack of civility in Washington will lead to violence or acts of terror.” The poll found that sentiment was shared by strong majorities across the political spectrum, ages, income levels, education and regions.

For John Paul Lederach, an international peace builder and expert in conflict transformation, the first step is to promote a mutual sense of belonging. That means meeting and serving people where they live, by physically going to their homes or neighborhoods. “A lot of our isolation,” he said, “is the degree to which people feel invisible. So, when you come and show up and have concern and conversation from their location, you’re rehumanizing the situation that has lost that connection at a very deep level.” Given trends like migration and virtual work and commerce, which make community harder to build and prioritize, we need physical common ground even more than ever.

But what about feuding groups that refuse to share space, whose distrust for each other has ignited into fear and anger? Historically this was how wars were fomented, since it was easy to demonize an enemy one was never going to encounter personally except on the battlefield. This formula for conflict has ramped up with the advent of 24/7 broadcasting and social media. Technology creates the illusion that we do know our enemies. We see them, we hear them in our own homes every day, at any hour we choose to look, even if the versions that we “know” are often deceptive and unidimensional. As a result, the people we learn to fear seem closer and scarier than they used to, and a sense of imminent threat makes our world feel less safe and hospitable. It erodes our sense that we all belong here.

This anxiety may not initially feel like the loneliness we associate with isolation. It can feel like passionate—if negative—engagement. But the natural response to protect ourselves in the face of threat is to close down and prejudge others. Much of this, according to a 2014 series of studies published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, is fueled by a cognitive bias known as “motive attribution asymmetry.” It’s the assumption that our beliefs are grounded in love, while our opponents’ are based on hatred.

Sociologist and author Parker J. Palmer, who founded the Center for Courage and Renewal to facilitate fellowship across divisions and differences, recalls Alexis de Tocqueville’s observations in Democracy in America: “He said that American democracy could not thrive without the pre-political layer of voluntary associations in which people gather in various forms of community: family, friendship groups, classrooms, workplaces, religious communities and civic spaces.” What happens in these gatherings, Palmer explains, is that people “remind themselves of their connectedness with one another and create a million microdemocracies upon which the macro-democracy depends.”

By “macrodemocracy,” he meant more than just voting. He meant civic engagement and participation. If I’m connected to the children in my neighborhood, I may be motivated to go to a school-board meeting, even if I don’t have kids. If I have friends who can’t drive, I’m more likely to engage in a campaign for better public transportation. Being connected to others gives us a stake in more than our own interests and increases our motivation to work together.

Our politicians used to understand this. Until fairly recently, members of all parties in Congress would meet at school functions because their kids went to the same schools. They played softball or met at the gym. They attended the same parties. Now Representatives travel back to their districts on weekends, their families often stay in their home state, and socializing across ideological lines is viewed as betrayal. As a result, Palmer’s “pre-political layers of association” have frayed and increasingly are being replaced by “post-political” connections that require agreement before connection. This makes it ever more difficult for politicians to work with one another. Meanwhile, the entire country is stuck in gridlock.

Yet of all the issues I worked on as surgeon general, loneliness elicited more interest than almost any other topic from both very conservative and very liberal members of Congress, from young and old people, and from urban and rural residents alike. After my presentations to mayors, medical societies and business leaders from around the world, it was what everyone seemed to want to talk about. I think this is because so many people have known loneliness themselves or have seen it in the people around them. It’s a universal condition that affects all of us directly or through the people we love.

The irony is that the antidote to loneliness, human connection, is also a universal condition. In fact, we are hardwired for connection—as we demonstrate every time we come together around a common purpose or crisis. Such was the collective action of the students in Parkland, Fla., after the 2018 mass shooting at their school claimed 17 lives. We also see this instinct in the outpouring of aid and assistance by volunteers that follows major hurricanes, tornadoes and earthquakes around the globe. And even now, as we face the global COVID-19 pandemic and resort to physical distancing to reduce the spread of the virus, we are recognizing that we cannot make it through the fear, danger and uncertainty of the current moment without supporting one another. Despite the polarized time in which we live, our community instincts remain alive and well. When we share a common purpose, when we feel a common urgency, when we hear a call for help that we are able to answer, most of us will step up and come together.

Murthy, a former surgeon general of the U.S., is the author of the upcoming book Together: The Healing Power of Human Connection in a Sometimes Lonely World, from which this piece was adapted

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness