Once upon a time, about six weeks ago, more than 50 members of our Cleveland neighborhood left the warmth of our homes on a snowy weeknight to gather for a conversation about race.

We live in the largest development built in the city of Cleveland since World War II, with 222 homes. We call it an “intentional” community in this deeply divided city. It is economically and racially diverse, and includes a number of LGBTQ families. We are white, black and Latino. We are working parents, empty nesters and retirees.

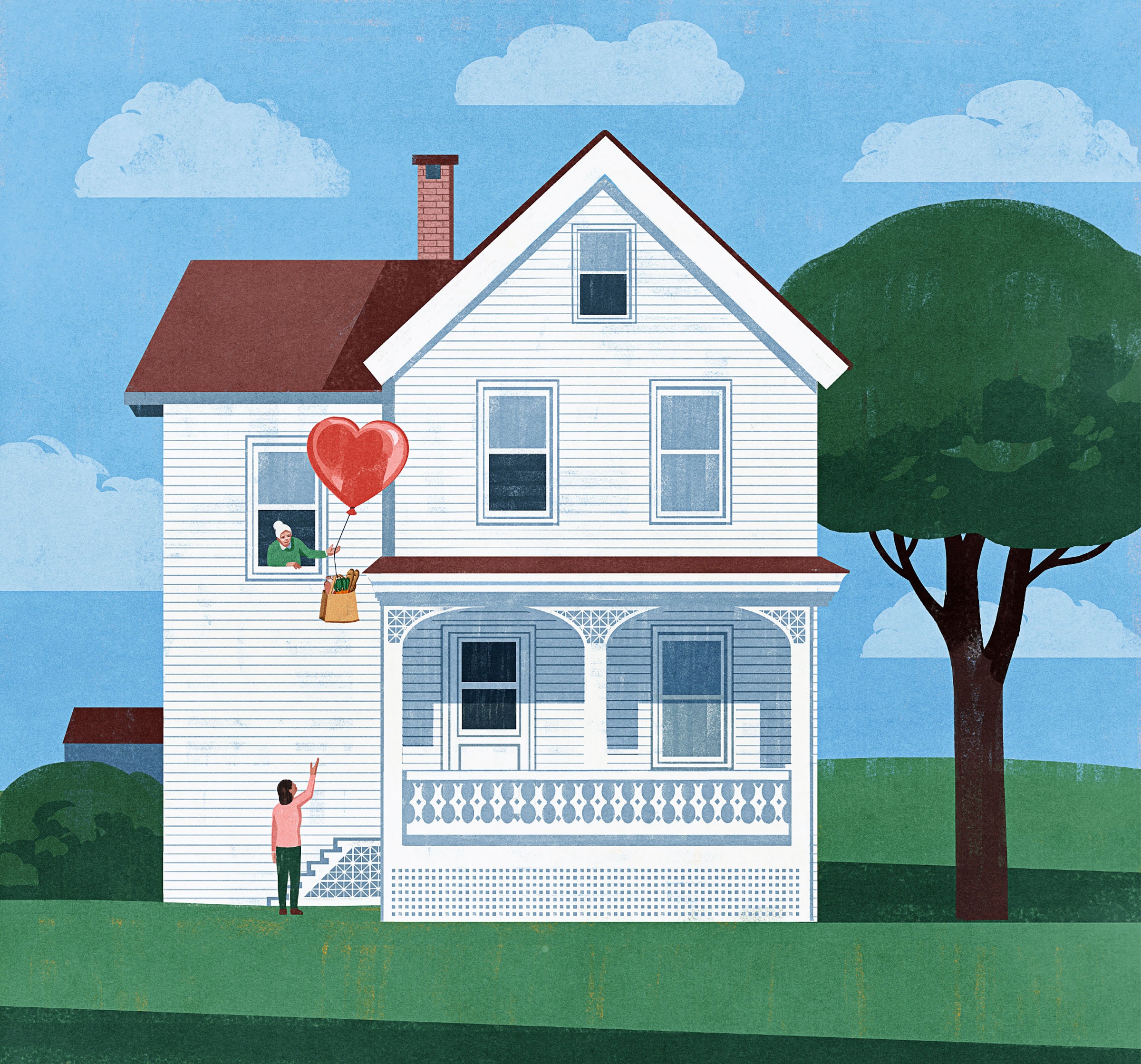

We live in modest, well-tended homes. Our yards are small, and we have lots of front porches and stoops. This is by design. We are meant to be neighbors, not side-by-side strangers. An evening walk on summer nights easily involves a dozen hellos and a few spontaneous conversations.

On this night in February, though, we had gathered to discuss what many of us wanted to believe could never happen here, even as some had always assumed it would. One exchange had led to another, and then another after that, and it was becoming clear that even in our beloved community of good intentions, racial tensions were bubbling up. Many white residents had been unaware, which was part of the problem. My friend the Rev. Kate Matthews, who is white and served on the board of our homeowners’ association, decided to do something about it.

Kate had recently read psychologist Deborah L. Plummer’s book Some of My Friends Are … about “the daunting challenges and untapped benefit of cross-racial friendships.” As Kate explained it to me, it had increasingly bothered her that despite the number of African Americans in her orbit, none of them were her close friends.

Through her work on the board, Kate had grown close to several black residents. Her conversations with them led her to reach out to Plummer, who had recently moved back to Cleveland. Would she be willing to lead us in a conversation on what it means to be a healthy, diverse community?

Plummer agreed. Kate and a team of volunteers peppered the neighborhood with flyers. Nearly 60—half of us black, half white—showed up.

For two hours, we explored the difference between “fellowship friends”—those people we know in social or professional settings—and “friends of the heart,” who are the ones who know our secrets and love us anyway. We talked about racism, a lot. We asked questions of one another and listened to the answers. Some of us winced. Others nodded in the universal language of “It’s about time.”

At the end of the discussion, as the snow continued to fall, we wrote notes to ourselves about what we planned to do to build relationships in our community. We sealed them in self-addressed envelopes, and Plummer promised to mail them to us in a few months. Seeing your own handwriting on an envelope addressed to you has a way of jolting one into accountability, I suspect.

We took our time leaving the meeting that night, lingering in our collective sigh of relief. We had more work to do, and we knew it. But we had a plan.

“We can start by being kinder,” a woman behind me said as we walked out the door. “Who doesn’t need kindness?”

Like most Americans, we had no idea what was coming.

Sometimes it seems the coronavirus has sidelined everything but the will to live. We are engaged in “social distancing,” which is meant to protect us but sounds like the language of suburban developments with big lawns and guard booths at the gate. Grocery shopping has become the 2020 version of food rationing. We never know what will be available from one day to the next. Some are hoarding, and those empty shelves challenge our faith in our fellow humans.

Early in March, our church abandoned the handshake during the passing of peace at Sunday worship. Some opted for elbow bumps, but I liked placing my hand over my heart and making eye contact, maybe leaning in a little. A moot point now, as our church, like so many other houses of worship, has suspended all gatherings. This is meant to keep us safe, of course. The mischief in me would like to discuss what it says about our faith in God, and in one another, to believe we’re better off apart. But then I think about how I always tell my husband, “Don’t die stupid,” after I find out he was talking on his cell phone while crossing a busy street. There’s only so much we can ask of God.

As always in this country, some are suffering more than others. The elderly and the sick are particularly vulnerable to COVID-19, but so are those who were at an economic and social disadvantage before this crisis started. When we pull out of our community, we don’t have to drive even a half mile in any direction to see the continued blight of urban neighborhoods that never recovered from the soaring rate of foreclosures in 2007. Every part of life is harsher when you live in poverty, including the judgment of those who see you as an embarrassing footnote in the fabled tale of downtown development and renewal.

Racial and economic inequality, voter suppression and foreign interference with our elections—it was all so overwhelming before the threat of this virus became all-consuming. The racial tensions we were hoping to address in our community are magnified tenfold by a President who daily insists on giving COVID-19 a racist name, which I wish my colleagues would stop repeating because it is potentially endangering the lives of Asian Americans. Trump has repeatedly made clear that he doesn’t care.

In our neighborhood, though, something is happening. We have shifted the topic but not the intention. Neighbors are checking in with one another more than we used to. We’re sharing more phone numbers and coordinating tag-team trips to the grocery and pharmacy. Far more of us, it seems, are taking walks throughout the day. We are yearning for the connection, even if six feet away.

One neighbor, recently widowed, is circulating flyers offering to run errands and asking for donations for a nearby neighborhood in need. Her list included diapers and feminine-hygiene products, and so I’ve just walked around the house gathering up the supplies we keep here for the daughters in our family, and our youngest grandchildren. They won’t be visiting soon, their parents insist, because they want to protect us. All those years of promising my children they would never have to worry about strong, mighty me, and here we are.

It is my habit to turn to poetry in times of stress. Today I picked up my copy of Mark Nepo’s Surviving Has Made Me Crazy. His poem “In the Other Kind of Time” reminds me of what our community, what every community, should be trying to do in this moment, in this time.

Come with me out of the cold

where we can put down the

notions we’ve been carrying

like torn flags into battle

We can throw them to the earth

or place them in the earth, and ask,

why these patterns in the first place?

If you want, we can repair them, if

they still seem true. Or we can

sing as they burn.

This is our truth: we’ve always needed one another. This is our bigger truth: we’re starting to act like it.

That conversation about race in our community would be put on hold only with our consent, and it appears we’ve collectively made a decision: permission denied. We are setting fire to that reckless disregard for our potential.

The porches and front stoops are living up to their promise. We wave hello and talk across our tiny yards. The questions rise like songs: “How are you holding up?” “What do you need?” “How can I help?” The chorus is always the same: I see you.

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness