Not many people were getting on airplanes in the U.S. on March 12, and even fewer were heading for the Grand Princess cruise ship. COVID-19 was discovered among the ship’s 2,400 passengers after it set sail from Hawaii, making the vessel about as popular as the Flying Dutchman; the Grand Princess had to loiter off the California coast for days before being given permission to berth.

But here was José Andrés, marching down an air bridge in Newark, N.J., for a 6:30 a.m. flight to San Francisco. His beige, many-pocketed vest and matching cap put out a vaguely fisherman vibe, but anyone who placed Andrés—he’s a celebrity chef—might also recognize the gear he changes into when he’s racing to the scene of disaster. The flight was long, and there was plenty of time to contemplate the dimensions of the catastrophe already silently spreading across the country below.

“I feel like if something major happens, the America we see from this window …” he says, trailing off as he looks out over the Rocky Mountains. He had mentioned the shortages of surgical masks and corona-virus tests, and now let the next thought remain unspoken. “This is like a movie, man. Maybe we’re overreacting. But it’s O.K. to overreact in this case.”

Andrés’ rapidly expanding charity, World Central Kitchen, is as prepared as anyone for this moment of unprecedented global crisis. The nonprofit stands up field kitchens to feed thousands of people fresh, nourishing, often hot meals as soon as possible at the scene of a hurricane, earthquake, tornado or flood. As a global public-health emergency, COVID-19 hasn’t been limited to any one place. But it pulverizes the economy as it rolls across the world, and people need money to eat. World Central Kitchen already is distributing meals in low-income neighborhoods in big cities like New York, and monitoring the globe for food shortages elsewhere, some sure to be acute.

In the meantime, Andrés is a lesson of leadership in crisis. In a catastrophe in which the response of the U.S. government has been slow, muddled and unsure, his kitchen models the behavior—nimble, confident, proactive—the general public needs in a crisis (and, so far, has provided it more reliably than the federal government). Consider the Grand Princess. President Donald Trump made crystal clear he would have preferred that people remain on the vessel so the infected passengers would not increase the tally of cases he appeared to see as a personal scoreboard (“I like the numbers being where they are”). Then, a few breaths later, the President said he was deferring to experts, which made life easier for the quarantined passengers and crew who disembarked, a few hundred at a time, over a week, but harder for Americans looking for the clear, unambiguous instruction that’s so essential to public health. “We have a President more worried about Wall Street going down,” says Andrés, “than about the virus itself.”

At the port of Oakland, where the Grand Princess finally docked, Andrés’ team made its own statement. Setting up a tent at the side of the ship, it forklifted fresh meals not only for the quarantined passengers but also for the crew. “When we hear about a tragedy, we all kind of get stuck on ‘What’s the best to way to help?’” playwright and producer Lin-Manuel Miranda, who first connected with Andrés in 2017 during the Hurricane Maria relief efforts, tells TIME. “He just hurries his ass over and gets down there.”

Andrés, at the age of 50, is charismatic, impulsive, fun, blunt and driven, an idealist who feeds thousands and a competitor who will knock you out of the lane on the basketball court. He is also among America’s best-known cooks. His ThinkFoodGroup of more than 30 restaurants includes locations in Washington, D.C.; Florida; California; New York and five other states; and the Bahamas. They run the gamut from avant-garde fare to a food court that the New York Times restaurant critic called the best new establishment in New York in 2019. But in recent years, Andrés, an immigrant from Spain, has attracted more attention with his humanitarian work. World Central Kitchen prepared nearly 4 million meals for residents of Puerto Rico in the wake of the devastation wrought by Maria (he titled his best-selling book about it We Fed an Island). The organization has launched feeding missions in 13 countries, serving some 15 million meals and corralling more than 45,000 volunteers. Andrés was nominated for the 2019 Nobel Peace Prize.

Upon landing in the Bay Area, he hopped on the phone with Nate Mook, World Central Kitchen’s executive director, to discuss a potential partnership with Panera Bread to give away meals. He put on a mask and visited the kitchen his organization had set up at the University of San Francisco, where several dozen workers prepared jambalaya and salads for quarantined passengers. He thanked his workers—many of whom are veterans of past feeding efforts—but noted the risks of overcrowding a relief kitchen in the era of COVID-19. “Less people is better,” he told a World Central Kitchen staffer. “If not, we’re going to fall like flies.”

Next stop: the cruise ship, to distribute meals. On the ride over the Bay Bridge to Oakland, Andrés was already managing past the task at hand, as he spoke to Mook about financing a mass feeding program. “This is going to be something remembered in the history books,” he says. “This is going to be beyond Sept. 11, beyond Katrina. Think big. Because every time we think big, we deliver. And the money always shows up.” Later that evening, Andrés and his staff huddled with leaders of an Oakland-based company, Revolution Foods, who have contracts to cook and deliver school lunches: they’ve continued operating during the COVID-19 emergency. Andrés urged the company’s CEO and head chef to isolate cooks so they steer clear of infection. He coached them on forging partnerships-: with restaurants ordered shuttered, Andrés noted, many cooks will soon be out of work and itching to help.

“My friends,” Andrés told his staff, “maybe this is why World Central Kitchen was created.”

It was during Hurricane Maria that Andrés learned to cut through government bureaucracy to fill a leadership vacuum and feed the masses. From a niche nonprofit supporting sustainable-food and clean-cooking initiatives in underdeveloped countries like Haiti, World Central Kitchen has become the world’s most prominent first responder for food. In some ways, the face of global disaster relief is a burly man fond of shouting “Boom!” when he hears something he likes, and leaning his body into yours when he wants to make a point. Andrés and his field workers flock to disaster sites across the world, often acting as some of the first on-the-ground social-media reporters. They’ve deployed to wildfires in California, an earthquake in Albania, a volcanic eruption in Guatemala.

When Hurricane Dorian made landfall in the Bahamas last September, World Central Kitchen commandeered helicopters and seaplanes to take meals to the Abaco Islands, which lay in rubble. “In the end, we brought hope as fast as anybody has ever done it,” says Andrés. “No one told me I’m in charge of feeding the Bahamas. I said I’m in charge of feeding the Bahamas.” This year, World Central Kitchen workers went to Australia to help residents affected by the bushfires, and to Tennessee after tornadoes in the Nashville area killed at least 25 people.

It was not caught flat-footed by the coronavirus. In February, World Central Kitchen forklifted food onto another infected Princess cruise ship, the Diamond Princess, docked off Yokohama, Japan. Field-operations chief Sam Bloch had flown from the bushfire mission in Australia to Los Angeles and rerouted himself back across the Pacific. On March 15, as states ordered public spaces closed, Andrés announced the conversion of five of his D.C.-area restaurants, and his outlet in New York City, into community kitchens. As of March 25, World Central Kitchen has worked with partners to coordinate delivery, via 160 distribution points, of more than 150,000 safe, packaged fresh meals for families in New York City; Washington, D.C.; Little Rock, Ark.; Oakland; New Orleans; Los Angeles; Miami; Boston; and Madrid. Across the country, the organization’s “Chefs for America” online map pinpoints 346 restaurants and 567 school districts providing meals. On March 23 and 24, Andrés drove around D.C. to give out more than 13,000 N95 respirator masks, left over from prior World Central Kitchen cruise feeding operations, to health care workers fighting COVID-19 on the front lines.

“We need to make sure we are building walls that are shorter and tables that are longer,” Andrés likes to say, making explicit his difference with Trump. He pulled out of a restaurant deal at Trump’s D.C. hotel after the candidate announced his campaign by referring to Mexicans as “rapists.” (The Trump Organization sued; ThinkFoodGroup countersued; the case was settled.) During the government shutdown in early 2019, World Central Kitchen and partners cooked 300,000 meals for furloughed federal workers living paycheck to paycheck. On a plane to Las Vegas recently, Andrés told me, a Trump supporter said to him that although he knew the chef didn’t like “my boy,” he still considered Andrés a good guy.

“What we’ve been able to do,” says Andrés, “is weaponize empathy. Without empathy, nothing works.”

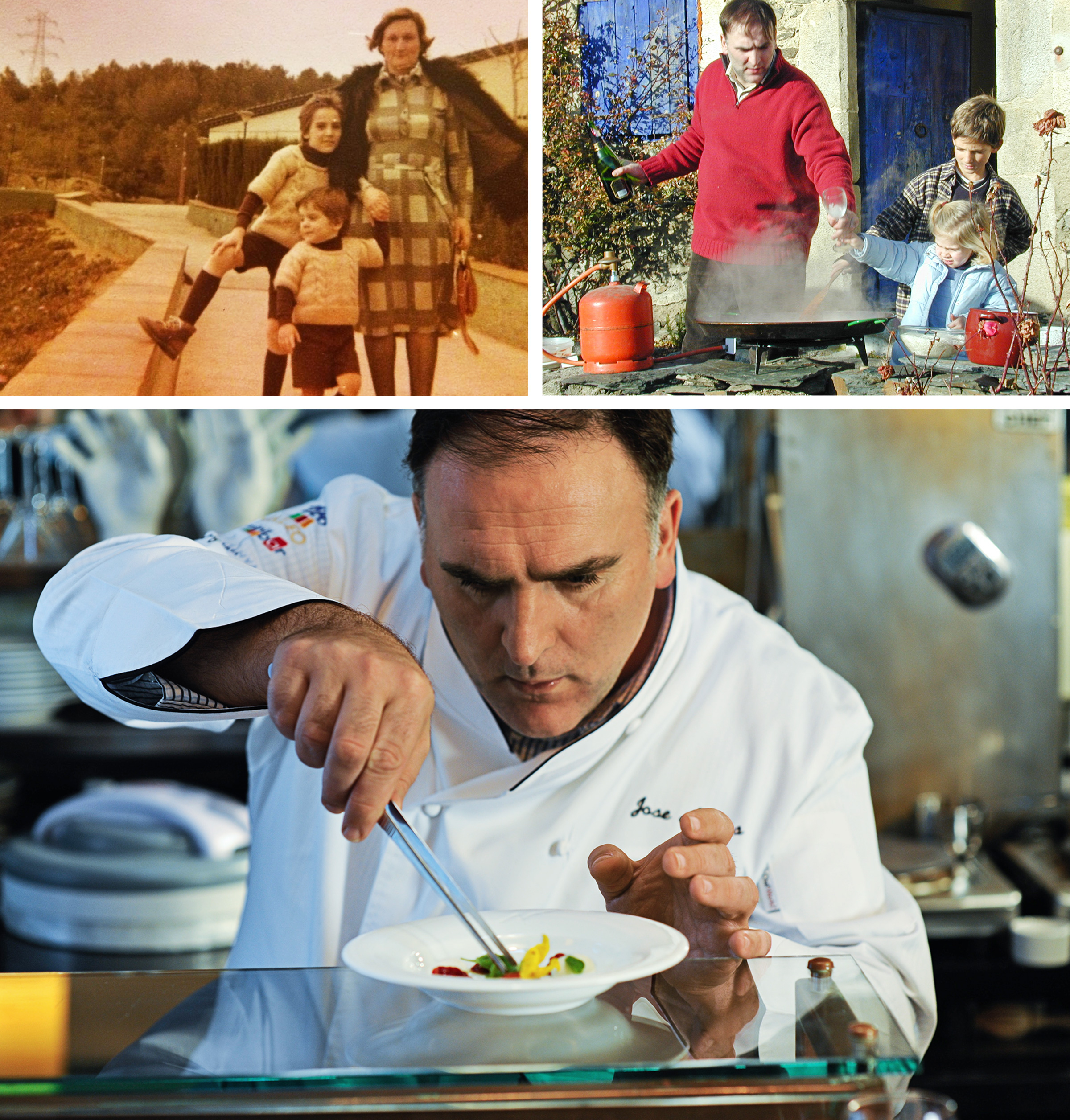

Andrés was raised in the north of Spain, the son of nurses. Cooking was always alluring. “The touching, the transformation of things, the smells of it, the tastes of it, it brought people together,” Andrés says. “I love clay. I love fire. Maybe I’m a distant relative of Prometheus.” He is fond of telling one story: when he was a boy, he always wanted to stir the paella pan, but his father wouldn’t let him cook. He first had to learn to control the fire.

After culinary school in Barcelona and a stint in the Spanish navy cooking for an admiral, Andrés arrived in New York City in 1991 as a 21-year-old chef with $50 in his pocket. He moved to D.C. a few years later to help start a Spanish-themed restaurant, Jaleo, and helped popularize tapas in the U.S. Success gave him the freedom to open more restaurants and experiment with new fare. In 2016, minibar, in D.C., which offers a tasting menu of a few dozen small courses, earned the coveted two-star Michelin rating. “He’s probably the most creative chef in the world today,” says French chef Eric Ripert, whose own flagship New York restaurant, Le Bernardin, regularly ranks among the best on the planet. Ripert points to a waffle stuffed with foie gras mousse, served at barmini—minibar’s companion cocktail and snack lounge—as an Andrés creation that blew him away. “Waffles are not supposed to be savory,” he says. “Your chances of success with that are almost none. You see it coming and you’re like, ‘What is that?’ It’s full of surprise.”

In an interview a few years back, Andrés, who became a U.S. citizen in 2013, said he speaks to his ingredients. But when I ask if he actually talks to his garlic, he says don’t take him literally. “If you are a cook and you don’t understand the history and physics behind water, of tomatoes, it’s very difficult for you to do anything. Come on, talking to ingredients is just, Are you aware of what you have in your hands? Are you deep in thought?”

While Andrés’ restaurants caught on in the 1990s and his profile continued to rise—a PBS show, Made in Spain, for example, debuted in 2008—he homed in on philanthropy. He lent time and resources to D.C. Central Kitchen, a local charity that not only feeds the capital’s homeless and residents in need but also trains them to find cooking jobs. It was in 2010—after he visited Haiti following the earthquake that year—that he founded World Central Kitchen. “My whole history with him has been listening to him and saying, ‘You’re crazy,’” says D.C. Central Kitchen founder Robert Egger. “Then he does it. At this point if he comes to me and has an idea for an intergalactic kitchen, I’m like, ‘F-cking A, that’s good. I’m on board.’”

The organization pitched in on Hurricane Sandy relief in 2012, and in August 2017, Andrés traveled to Houston to help mobilize chefs after Hurricane Harvey. The work all led up to Hurricane Maria, which made landfall that September. “Puerto Rico was that moment where it’s like, O.K., it’s time to put into practice all that we’ve been soaking up over the years,” says Mook, World Central Kitchen’s executive director. “We saw the sheer paralysis of the government’s response. We realized we were on the brink of a humanitarian crisis. We said, Let’s start somewhere. Let’s start cooking.” (Andrés appeared on TIME’s list of the 100 most influential people in the world in both 2012 and 2018.)

World Central Kitchen has figured out that rather than relying on packaged food airlifted in from the outside—“meals ready to eat” (MREs) in relief parlance—Andrés and his team can tap into existing supply chains and local chefs to prepare hot meals. As its profile has expanded, its revenues have ballooned from around $650,000 in 2016 to $28.5 million in 2019, and the organization now has the wherewithal to hire local help—as well as send out its own operations experts—to kick-start the food economy. Some two-thirds of World Central Kitchen’s 2019 revenues, or $19.1 million, came from individual donations, ranging from large gifts from philanthropists (including from Marc and Lynne Benioff, TIME’s owners and co-chairs) to kids giving $6 out of their allowance. Former President Bill Clinton, whose Clinton Global Initiative has supported World Central Kitchen, says Andrés’ empathic action is more crucial than ever in these divided times. “If you spend more time on your fears than your hopes, on your resentments than your compassions, and you divide people up, in an interdependent world, bad things are going to happen,” Clinton, who first spent significant time with Andrés in Haiti after the earthquake, tells TIME. “If that’s all you do, you’re not helping the people who have been victimized or left behind or overlooked. He’s a walking model of what the 21st century citizen should be.”

About two months before his trip to Oakland, Andrés stomped into another airport, in San Juan, the first person off his flight from Washington, D.C. “Go do your thing, chef,” a man sitting at another gate told him as he made his way through the terminal. A 6.4-magnitude earthquake had brought Andrés back. A car was waiting to take him to the south, where the tremors damaged homes and left hungry people sleeping under tents. As his ride rushed through a lush green Puerto Rican mountainside, Andrés offered a master class in multitasking, one moment conducting ThinkFoodGroup business over the phone—“I never saw the deal. I need to see the deal before I sign sh-t,” he barked at one executive—while in another prepping his World Central Kitchen field workers for his arrival. “I’ve got good news and bad news,” he told one of them. “The bad news is, I’m coming …”

Working for the blunt Andrés is not for the faint of heart. On the other hand, the chaos of a restaurant kitchen translates into a disaster area. He often rubs his eyes and tugs at his beard, before expressing frustration. “I would like to say you put too much food on a tray,” he tells a few of his workers in Puerto Rico. “But that never f-cking happens.”

During his 36 hours in Puerto Rico, Andrés pinballed to some half dozen World Central Kitchen sites to assist with the feeding efforts, at baseball fields, a track-and-field facility and a smaller indoor kitchen in the city of Ponce, where workers prepared ham-and-cheese sandwiches with globs of mayo. (“Makes them easy for the elderly to chew,” Andrés says.) In Peñuelas, the chef shared a quiet conversation with an overwhelmed food-truck operator World Central Kitchen had hired, urging her to change the menu for dinner before patting her on the back and departing for his next stop. In Guayanilla, Andrés went bed to bed handing out solar lights to frightened residents sleeping outside in the dark. In Yauco, he stirred meat sauce in one of World Central Kitchen’s signature giant paella pans. Within days of the earthquake, Andrés’ operation was serving 12,000 meals a day in Puerto Rico.

On the early-morning flight to Fort Lauderdale, Andrés earned the title of loudest snorer on board. He had been up late the previous night, enjoying a few pops of his go-to drink, the rum sour, at the San Juan restaurant whose namesake chef, Jose Enrique, first opened his kitchen doors to Andrés after Maria. And he had woken up that morning for a radio interview before the flight. In Florida, he would catch a private charter to Hurricane Dorian–damaged Marsh Harbour in the Bahamas, where hollowed-out cars still lie by the side of the road and only a stove remains where a kitchen once stood in most people’s homes. Although the hurricane had struck more than three months earlier, World Central Kitchen still had a strong presence: Andrés takes pride that his team doesn’t just parachute in. They stick around.

Andrés went door to door, distributing some two dozen hot meals, continuing his deliveries well past dark. Afterward, he was genuinely hurt that a few of his relief workers were too wiped out to join him for dinner and a few drinks. He napped again on the ride back to the hotel—his head bobbed with such force, it seemed in danger of collapsing to the ground. But once at the hotel he wanted to stay up a little longer, sip Irish whiskey on the beach and stare at the stars.

Perhaps Andrés crashes so hard because he lives in perpetual motion, often acting on impulse. His “plans” deserve quotation marks. He’ll shout, “Let’s go,” in his booming voice—then stick around for another hour, taking pictures, lugging a crate of apples to help feed people, talking to anyone within earshot. After leaving the cruise ship in Oakland, Andrés and his team were scheduled to hunker down in a San Francisco hotel room to figure out their strategy for feeding America in the wake of COVID-19. A staffer worked the phones to reserve a conference room. First, however, a spontaneous lunch interrupted: Andrés took five workers to a favorite Chinese restaurant, which was nearly empty because of coronavirus fears, for piles of dim sum. Then Andrés declared he wanted to move the meeting to a park. Then, instead of squatting in grass, Andrés decided that everyone, including himself, needed to find a barber to shave their beards and shorten their hair after a social-media user pointed out that facial hair can reduce the effectiveness of the N95 masks World Central Kitchen workers had been wearing. Andrés, who had been up until at least 2 a.m. on the East Coast before catching his early-morning transcontinental flight, passed out in the barber’s chair, shaving cream smeared across his neck.

What looks like a scatterbrained approach can work in managing a crisis: while visiting the Bahamas, Andrés was in constant contact with his team in Puerto Rico, where another 6.0-magnitude earthquake hit after he left. But human relations are something else. If he’s idling on Twitter when you ask for his attention, it can be grating. “He’s the salt to my life because he really brings the color and the flavor,” says Andrés’ wife Patricia, who also hails from Spain; she met him in D.C. in the 1990s. “But sometimes I want to kill him, O.K.? Don’t misunderstand me. Or throw him out the window.”

Andrés is sometimes so in his head and on mission, he’s oblivious to his surroundings. He’ll open a car door before the vehicle comes to a complete stop. He has a habit of walking in circles, staring straight ahead, while on important cell-phone calls: in Marsh Harbour, a car pulling into a takeout shop nearly hit him. In Ponce, while showing someone the proper angle at which he wanted to take a picture of lettuce growing in a greenhouse, he leaned against a rail and nearly took out a portion of the crop.

But a tendency to distraction belies his intense focus on whatever he’s trying to accomplish. Andrés plays to win. The day before the NBA’s All-Star Celebrity Game in February, I joined him for a training session at the National Basketball Players Association gym in New York City. His friend José Calderón, a former NBA player from Spain, works as a special assistant to the union’s executive director. During a game of 3-on-3, Andrés fouled me with his shoulders, barely attempting to move his feet. He employed similar tactics, it turns out, while playing with his daughters in the driveway of their Bethesda, Md., home. “We were 10, 12 years old, and he didn’t care,” says his eldest daughter Carlota, 21. “We were on the floor.” He wasn’t much nicer to the officials at their youth hoops contests. “He would get kicked out of my games multiple times,” Carlota says. “I think it started when I was in second grade.”

He brings both temper and tenderness. “I am getting very anxious,” he said in a raised voice at one of his relief workers over the phone in Puerto Rico. “Can we for once f-cking show up at the same time and the same place … Are we in control, or are we not in control?” But he’ll later tell his crew how proud he is of them, or how much he loves them. When he got wind that classmates were telling the 9-year-old daughter of one of his workers that she might get coronavirus because her father was working near the cruise ship, Andrés grabbed his colleague’s phone and recorded a video message for her and two younger siblings. “Your daddy is a hero, period,” Andrés said, choking up slightly. “So don’t worry, your daddy is going to be home soon and he is going to be taking care of all of you. And I only want you to be super proud of your dad.”

In the Bahamas, a woman yelled out to Andrés from her car and simply put her hands together, as if she were in church; it was her way of telling him he’s a blessing. On his way to his office in D.C. in February, a woman from Japan stopped to thank him for feeding the cruise-ship passengers docked in Yokohama. And as he walked through downtown San Francisco, puffing on a cigar, a woman approached him gingerly to tell him that she’s donated to World Central Kitchen and that it was an honor to meet him. She then tiptoed away, as if she’d just disturbed rare air.

His decision to head to San Francisco—where one of his workers wore a hazmat suit as he drove the forklift of food to the cruise ship—didn’t make much sense to me. The World Central Kitchen team was handling the feeding just fine. The mission was winding down. D.C. was going to serve as the Chefs for America command center to address hunger caused by COVID-19 disruptions. So why would the man who says he “wants to take the lead in feeding America” after the outbreak risk getting sick, or grounded, 2,500 miles away from home base?

This line of inquiry annoys him. “Sh-t, I want to be with the guys to see it and give thanks,” says Andrés on the flight west. “What a question to ask. Like, why the f-ck do you get married?” At the University of San Francisco kitchen, a chef who has worked on prior World Central Kitchen missions lights up when she spots Andrés. They exchange a hug. Andrés turns my way. “You ask me why I come,” he says. “What the f-ck? What’s wrong with you?”

Andrés has something in common with his buddy Clinton: he craves connecting with people. His public face—yukking it up on The Late Show with Stephen Colbert, pumping up World Central Kitchen on social media, giving booming speeches to audiences that hang on every word—has earned him a reputation as a tireless advocate for humanity. But he doesn’t always feel so fresh himself. On the flight from Florida to the Bahamas in January, Andrés finally set aside his phone, reclined and admitted that the expectations of feeding the world, and running some 30 restaurants, weigh on him. Over the past few years, both his parents have died. His good friend Anthony Bourdain committed suicide. Two of his daughters left for college. “You wake up in the morning, and you’re like, oooof,” says Andrés. Sometimes he feels like staying in bed. “All of this is happening in front of you and you feel like you’re losing control.”

He also has to fight getting in too deep. “My biggest worry is that the dream of feeding the world takes a toll on me that it becomes almost sickening,” Andrés says. “You become totally obsessed with it. You’re enjoying dinner somewhere, and you’re checking your phone. Has there been an earthquake? What’s happening in Syria? What the f-ck happened there, how are we not there? I have a company to run. I have a family. I cannot disappear from the life of other people that need me too.”

Patricia remembers her husband waking up one morning anxious around three years ago, before Hurricane Maria, when he was already a famed, award-winning chef. “He’s like, What am I going to do with my life?” she says. “Am I doing enough? I’m not doing anything.” He still expresses such sentiments. “He doesn’t look at what he has done,” she says. “He is looking at what he still has to do.”

Those closest to him worry that all the work is wearing him down. “I wish he could lose some weight and get fit,” says Patricia. That Nobel Peace Prize nomination and the global adoration are nice and all: just imagine, she jokingly tells him, what he could do if he were in better shape.

“The only thing I worry is, I don’t think he spends enough time taking care of José,” says Clinton. “He works a lot. I don’t want him to burn out. I don’t want him to drop dead someday because he has a heart attack, because he never took the time to exercise, and relax and do what he needs to do. He’s a treasure. He’s a national treasure for us, and a world treasure now. He’s really one of the most special people I’ve ever known.”

Andrés shoos away all calls to slim down: he insists he runs 325 days a year. He allows, however, that the suffering he’s seen up close at disaster scenes—dead bodies, elderly people sleeping in soiled beds, starving people eating roots and drinking filthy water—strains his mind. To cope, he sometimes turns to what he calls a “strange thought” for solace. The thought is that as more climate disasters inevitably hit both the developed and under-developed worlds, poor people in places like the Bahamas and Puerto Rico may at least be better equipped to cope. “This gives me a little bit of strange happiness only in the sense saying, You know one thing? Maybe life is preparing them for a worse moment,” says Andrés. “And actually the fittest will survive and it’s not me, it’s not us, it’s them.”

Meanwhile, Andrés vows that World Central Kitchen will continue to grow. Splitting time between the nonprofit and his restaurants hadn’t hurt business before the COVID-19 shutdown. On the contrary, revenues had doubled in the past two years, thanks in large part to the opening of Mercado Little Spain, the food market in Manhattan’s Hudson Yards complex, though the goodwill Andrés has earned through World Central Kitchen and his rising profile have also helped. Andrés believes World Central Kitchen, at 10 years old, is still in its infancy. He and his team are learning as they go, and he’s confident that with COVID-19 threatening Americans’ familiar way of living, World Central Kitchen will pass its biggest test yet.

“We will be there to cover the blind spots that the system will have,” Andrés says curbside at SFO, before boarding his flight back home to D.C. “You cannot expect in a crisis like this that the government will cover everything, that the super big NGOs will cover everything. We’ve already been the first ones in the front lines. And I have a feeling we’ll be the last ones leaving the front lines. That’s always the case.”

Let’s go.

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- 11 New Books to Read in February

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

- Introducing the 2025 Closers