There once was a time when people from all walks of life, and any region of the country, would have known a little something about a world-class conductor and composer like Leonard Bernstein. You didn’t have to care much about classical music; you might have seen him on TV, being interviewed by Edward R. Murrow, or if you were a kid, you might have caught an episode of his Young People’s Concerts on CBS. You could be a plumber, or a plumber’s kid, and easily have some entrée into his rarefied world, and once you stepped in, you might be captivated by his urbane charisma, or flummoxed by his wily intelligence. In one of the Young People’s Concerts—you can watch it on YouTube—he waves his baton gloriously as the New York Philharmonic swoops and swerves though one movement of Haydn’s Symphony No. 88. "Didn’t that sound great?" he asks the audience, both in the studio and at home, before outlining precisely what was wrong with the way the orchestra had intentionally played the piece. Punked! But he’d lured you in with his gusto and grace, and you’d learned something—he made you feel respected, not duped. No wonder Lydia Tár adored him.

Bradley Cooper works a similar kind of seduction in his superb and deeply felt Leonard Bernstein opus Maestro, premiering at the Venice Film Festival. Cooper both directed and stars in the picture, which has already courted some controversy over the prosthetic nose he chose to wear for the role. (Bernstein was Jewish; Cooper is not.) Some have seen Cooper’s choice as anti-Semitic, though Bernstein’s children, and the Anti-Defamation League, have defended it. On the quieter side of the argument are those who simply find a fantastic honker insanely attractive. Cooper’s nose is perfectly fine, but Bernstein had a great, distinctive, sexy one. If you’re playing a character who was wildly alluring, to both men and women, why wouldn’t you want to emphasize one of his most distinguishing features?

The bigger frustration is that arguments over the prosthesis—made by people who haven’t yet seen the film—only drag attention away from all that Maestro is. This is a complex and sophisticated picture, the kind of grown-up love story we see all too rarely these days, especially when it comes to starry, big-ticket moviemaking. It’s entertaining and robust and forthright; it’s also tremendously sad, not necessarily in a bring-your-hanky way, but in a deeper, more truthful way. This isn’t just a story about a selfish, eminently likable genius (though it’s partly that); it’s a picture that dives into the not-fully knowable complexities of love and desire. When it ends, you might feel both elated and slightly bereft. It’s a picture that gives you something you didn’t know you needed.

Maestro opens with sketches of two different Bernsteins who, by the end of the film, have merged into one: There’s the older Bernstein, roughly in his sixties, who’s being filmed by a television crew, his voice weathered and adenoidal as he expresses autumnal sorrow over the then-recent loss of his wife. And there’s the younger one, his limbs seemingly connected by springs, who leaps naked out of bed like a golden god, so full of erotic energy he can barely contain himself—he beats a flirtatious drum tattoo on the bare butt of the sleepy guy he’s just spent the night with. Both of these Bernsteins are the real deal; the movie signals early on that there’s nothing tidy about this fireball of a life.

From there, Cooper—who co-wrote the script with Josh Singer—details Bernstein’s rise as an ebullient, expressive conductor and a composer whose music spoke in an urbane but wholly approachable pop-music vernacular. The school’s-out joy of On the Town, the romantic boldness of West Side Story—it’s hard to imagine anyone feeling shut out by this music. Bernstein had a flair for inclusivity. He was also charming as hell, and as Cooper plays him, it’s little wonder that he attracted attention from members of both sexes.

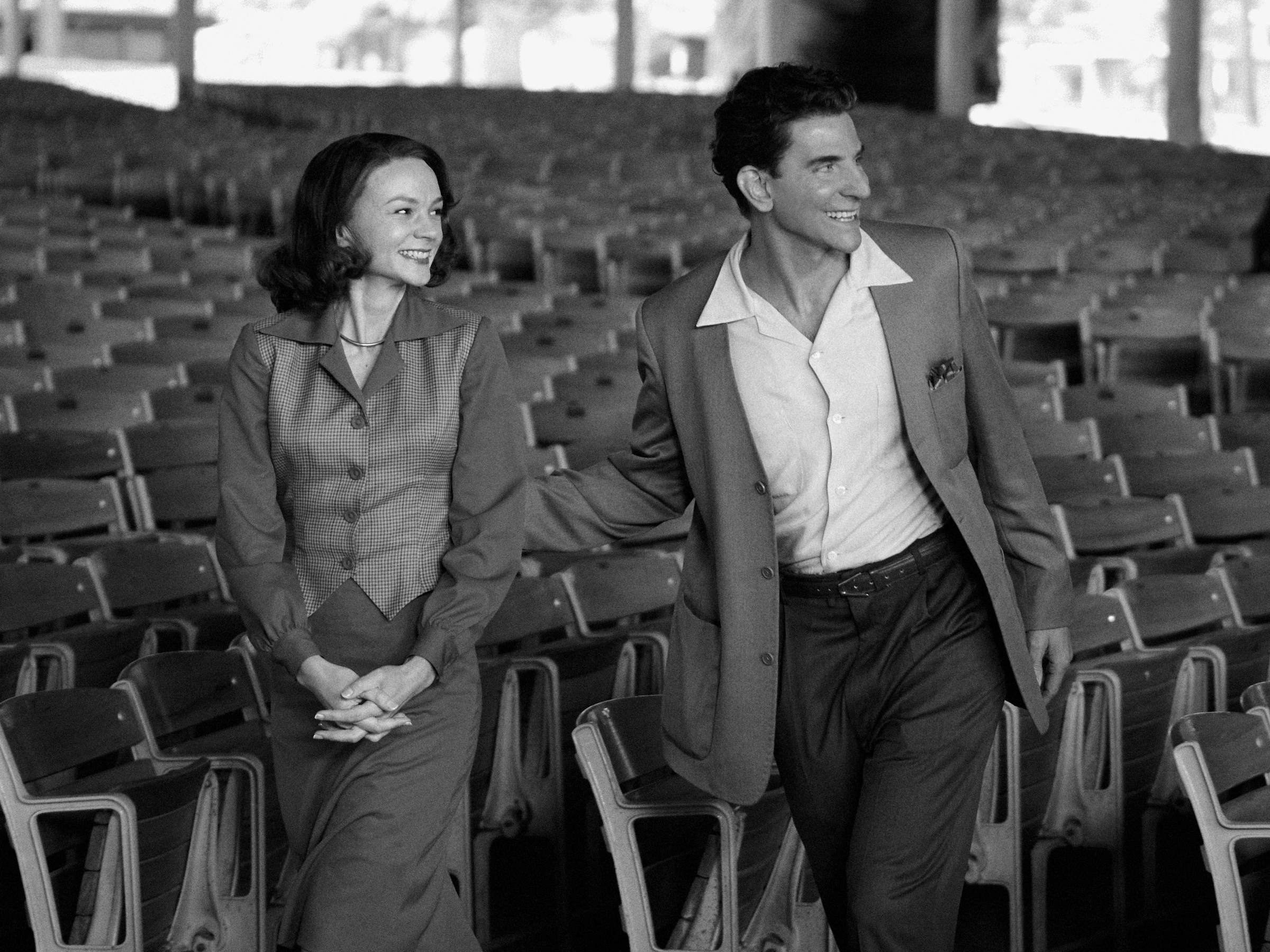

But his first meeting with the Chilean-born actor Felicia Montealegre (played beautifully, with a kind of genteel warmth, by Carey Mulligan) sets off a particularly mighty spark. The two fall deeply in love, and though Felicia hints discreetly that she knows all about Leonard’s “other” life, they vow to make some sort of union work. Before they know it, they’ve got two children—eventually three—and both have achieved the career success they’ve dreamed of, though Leonard’s star will shine brighter and longer.

Their loyalty is intense. But loyalty isn’t the same as fidelity, an idea Cooper explores fearlessly. Early in their courtship, Leonard introduces Felicia to the clarinetist he’s been sleeping with, played by Matt Bomer, not bothering to hide his newfound hetero-exultation. His abandoned love greets Felicia warmly, as if welcoming her into a family, the family of people who love Lenny. Yet the flicker of sadness that crosses Bomer’s face could be a novel unto itself. He knows what he’s just lost, while Leonard can see nothing beyond his own self-centered bliss.

It’s a moment of intense callousness played out with the lightness of an operetta. Cooper is happy to explore Leonard’s charm, but he finds the heartlessness in this character too: at times his eyes look like small, steely pin-dots, focused only on his own goals and desires. Those include wanting a family, and the scenes of the Bernsteins’ at-home life, much of it set in a grand-yet-welcoming Connecticut house, make it clear how much this self-absorbed, driven man truly loved his kids. (The oldest, Jamie, is played by Maya Hawke, who cuts a revealing window into what it must have been like to grow up in this far-from-average household.)

But Maestro doesn't soft-pedal the marital tension between Leonard and Felicia. At one point, some ten years into the marriage, Felicia watches as her husband seduces a handsome swain at one of the couple’s lavish parties in their upper-West Side flat—she’s more exasperated than hurt, but either way, Mulligan lets us see that the concessions Felicia has made for the sake of her marriage are wearing her down. A few years later, she gives up entirely on making it work. The two fight bitterly—it’s Thanksgiving Day, and with the kids laughing and shouting in the other room as the Macy’s parade balloons float by the apartment windows, Felicia lets loose with a tirade of accusations and resentments, all of them justified. It’s like Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf, with a cameo from a floating, larger-than-life Snoopy. Felicia’s rage, as Mulligan spins it out, fills the room beyond its capacity, and not even the brilliant Leonard knows how to respond. I’ve never seen a depiction of brutal discord quite like it. (Cinematographer Matthew Libatique, working here in both black-and-white and color, is adept at capturing both marital closeness and claustrophobia, sometimes even within the same frame.)

Yet this is always a love story: Cooper and Mulligan play out a devotion that survived whatever may have played out in one bedroom or another; there's a tender carnality between them. At the same time, Maestro is clear about Leonard’s attraction to, and his life with, other men. This is as far from a conversion-therapy fairytale as you can get. It’s more about loving people as they really are, sometimes the hardest task any of us is called upon to do. Since the 1960s, each generation has loudly celebrated its right to sexual freedom. But it’s completely possible to fall in love with someone who doesn’t fit neatly into your own zone of sexual orientation. And one person’s notion of sexual freedom can mean another person’s heartbreak. Maestro faces that truth squarely.

How, then, can this movie still be filled with so much joy? (It is also, incidentally, filled with smoking, which we absolutely must not do in real life, but which we should enjoy to the fullest when we see it in the movies.) In the end, you’re not likely to feel sorry for Leonard and Felicia; somehow, together they just worked. And if Felicia is the most overtly sympathetic character in Maestro, Cooper’s Leonard has so much windmilling vitality that it’s a pleasure to be in his orbit, even when he’s being impossible. In a re-creation of the real-life interview the couple conducted with Murrow in 1955, they sit cozily on a couch, a hugely successful 36-year-old composer-conductor and his Broadway-star wife. Together, they’re the picture of refinement. And then, in answer to one of Murrow’s question, Leonard’s face turns grave as he reflects on how a person can be torn in two when he’s both introspective, as a composer must be, and outgoing, as a conductor—who is also a communicator—must be. He turns it into a joke about schizophrenia. But he knows he’s both; how to reconcile the two? At the podium, Cooper as Leonard clarifies the mystery. He taps at the air with his baton, as if drawing with sound; his musicians follow along, giving him all he yearns to hear. The elation on his face, a private ecstasy that he bestows, like a gift, on the audience, suddenly makes the world seem ten times larger, and more beautiful, than it did before the music started. Cooper plays Leonard Bernstein as a man who belonged to everybody—and still does.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com