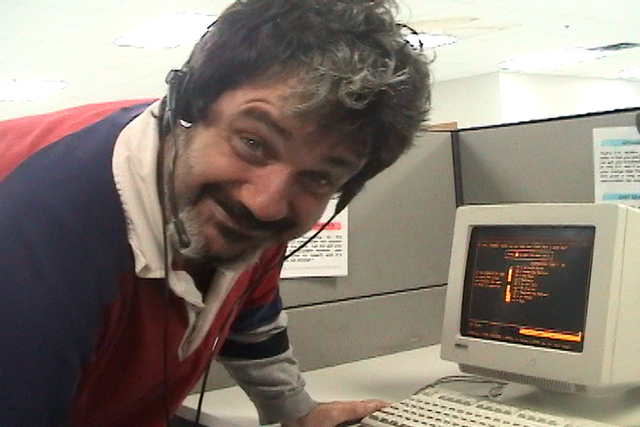

In 2001, Sam Lipman-Stern was a teenage high school dropout working at Civic Development Group (CDG), a telemarketing company that operated out of central New Jersey. He’d developed a love for film after being gifted a camcorder by a family friend and decided to document his workplace—a peculiar establishment that, he would discover, pocketed millions of dollars of donations via phone calls made by former inmates calling on behalf of charitable organizations. This all happened amid an office filled with drug use, partying, and impromptu tattooing.

“It was like a dysfunctional family,” Lipman-Stern tells TIME. “You'd have a murderer on your right hand side and a bank robber on your left. You just couldn’t write these characters up.” Among the all-too real characters was Lipman-Stern’s former colleague Pat Pespas, who agreed to participate in the project to document the absurdity of their job.

Nearly two decades later, their recordings have become HBO’s latest documentary series Telemarketers, directed and produced by Benny Safdie, Josh Safdie, Danny McBride, and David Gordon Green. The series is first of its kind—a deep dive into the world of telemarketing and how CDG, which at its height was the biggest telemarketing fundraising company, has inspired telemarketing copycats even after its downfall.

Read More: Telemarketers Is a Wild Scammer Epic—and One of the Most Exciting Docuseries in Years

The first episode of the three part series that premiered on Aug. 13 uncovered what it was like to work at CDG and how the company influenced the telemarketing industry. Episode 2, out Sunday, explores how CDG worked through loopholes to further their scheme, and the role that the charities they were calling on behalf of played. The finale will wrap the story on Aug. 27, spinning forward to see where these scams stand now and examining the key players that keep the system afloat.

The history of telemarketing

Well before smartphones came with warnings about spam calls with the “Scam Likely” label, companies like CDG pioneered the advertising tactic of having employees solicit donations from citizens over the phone to make millions of dollars of profit.

CDG, which was founded in the early 1990’s, ran on a simple model: the telemarketing company made calls on behalf of nonprofits and charities, another loosely regulated industry. Telemarketers reveals how the company’s leaders, David Keezer, Marc Keezer, Brian Pasch, Glenn Pasch, and Steve Pasch, came up with the scheme and scripts, and pushed to franchise their call centers. The workers in these offices, or “hopeless places,” were merely middlemen, former CDG telemarketer Billy Fedor says in episode 1.

CDG’s callers, who were expected to meet quotas, made pitches to local civilians to convince them to donate to charitable causes, including helping police, veterans, and cancer research. Of the money from those who donated, only about 10% of the contribution went to the intended charity (the rest was pocketed by CDG), according to Telemarketers. In exchange, they received sticker decals from police unions, like the Fraternal Order of Police (FOP), the world's largest organization of sworn law enforcement officers.

CDG employees would read from a script that prepared them with rebuttals for any potential reason someone wouldn’t want or be able to donate. Lipman-Stern says the telemarketers largely consisted of “people living on the edge,” those who had dropped out of school or were formerly incarcerated and unable to find work elsewhere. They became key to making CDG run.

“The model seems to hire ex-convicts and drug addicts because they're great hustlers,” said Lipman-Stern. “They know how to get money out of people and they're not going to say anything about suspicious activities.”

But Telemarketers aims to humanize the individuals making the phone calls. Lipman-Stern interviews several of his former colleagues, bringing out their perspective from working these minimum wage, under-regulated jobs. “We never wanted to demonize the callers. These were people who couldn’t get another job and that were in the prison pipeline,” he says.

Telemarketers’ success depended largely on how they sounded on the phone—a diction that required balancing warmth and assertiveness to secure a deal. A CDG employee calling someone on behalf of the FOP would try to sound like a caricature of an officer. “I remember people asking me: Are you a police officer?” says Lipman-Stern. “I'm like ‘No, I'm 14 and I kind of dropped out of school,’ while continuing in the cop voice.”

What happened to CDG?

In 1998 CDG was sued by the Federal Trade Commision for falsely advertising their use of donations. In 2007, the Department of Justice doubled down, alleging CDG had not changed their ways, and instead changed its business model by saying they were calling as “consultants” on behalf of groups like the FOP, instead of as telemarketers. They’d even go as far to say that 100% of donations were going to the organizations—which was far from the truth.

In 2010 the FTC ordered CDG to pay $19 million in fines and get out of the fundraising business. But no criminal charges were filed against the Keezer and Pasch brothers and its shutdown was temporary—as episode 2 of Telemarketers details, the company returned with a new tactic and prompted copycat companies along with them.

“I’ll tell you the secret about CDG. They don’t ever change,” said Pespas in the documentary. “It’s ‘Where's the next little loophole we can get through?’”

The story isn’t just about CDG’s owners, the telemarketers, and the donors on the other end of their phone calls. As revealed in episode 2, the charities and organizations that CDG called on behalf of (like the FOP) are just as directly involved in this telemarketing phenomenon.

How Telemarketers’ expose of a billion dollar scam came to HBO

Before Telemarketers deep dive, the public’s knowledge on how the scheme operated was limited. Lipmam-Stern, Pespas and other former telemarketers were perfectly positioned to expose the behind-the-scenes of an industry that had long gone under the radar due to lack of accountability and political action.

“Pat and I were like, ‘We got to tell his story to the world,” he says. “We're the only people that can because we work in this and we're from this.”

In the decades since Lipman-Stern worked in telemarketing, the industry hasn’t slowed down. “Everyone would always tell me that they got the call from telemarketers,” he says. It made his choice to film the OG-telemarketing work environment—a decision originally encouraged by his prior CDG manager “Big Ed” Hilger—more relevant than ever before because the schemes have only gotten more aggressive and plentiful.

And the telling of CDG’s story wouldn’t be possible without Pespas, one of CDG’s best salesmen whose charismatic personality and demeanor brings true comedy to Telemarketers. “We got to take them down from the inside,” he says in episode 1, in which he’s seen calling out injustices and social causes he cared about including global warming, and flagging his skepticism of the work CDG was performing.

At one point Lipman-Stern and Pespas discussed the ideal scenario of this work potentially getting to the masses. “There's old footage of Pat and I that never was released saying one day maybe we'll get this on HBO,” he recalls. “That was actually our dream. We never really thought it was tangible or would happen back then.”

The opportunity was made possible after Lipman-Stern connected with his family member Adam Bhala Lough, who is a film director, and bridged a connection with the Safdie brothers and actor and producer Danny McBride, who helped build the decades old footage into a documentary. Bhala Lough co-directed Telemarketers with Lipman-Stern.

To Lipman-Stern, the story isn’t all bad. “The best thing about this industry was the jobs that it provided to people that were unemployable, from a 14-year-old high school dropout graffiti writer with an anxiety disorder to Pat,” he says, adding that the story also reflects the generosity of the millions whose intent was to give money to charitable causes. “The nonprofit space is incredible. It just wasn’t the ones we were calling for.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Mariah Espada at mariah.espada@time.com