Don’t be put off by the snoozy title: Telemarketers is one of the most exciting documentaries I’ve seen in years. Effortlessly dodging, and sometimes subtly parodying, every maudlin cliché of the true-crime genre, the three-part HBO series, debuting Aug. 13, is a first-person odyssey through the legal gray area of call-center fundraising. At first, the mood is reminiscent of cult docs like Heavy Metal Parking Lot and American Movie—funny, character-rich portraits of misfit subcultures. But then the misfits realize they’re pawns in a noxious scam. And they embark on a quest to expose it.

The saga begins with Civic Development Group, the New Jersey-based telemarketing company where our narrator Sam Lipman-Stern, who co-directed the series with Adam Bhala Lough, worked for seven years after dropping out of high school in the early 2000s. CDG’s self-evidently shady business model entailed raising funds on behalf of nonprofits, usually local lodges of the Fraternal Order of Police, but keeping something like 90% of the proceeds. The company would hire just about anyone, so its ranks swelled with ex-cons, addicts, and others who struggled to obtain or hold onto straight jobs. Its leadership had no interest in enforcing white-collar office norms, so as long as the money was pouring in, employees ran wild.

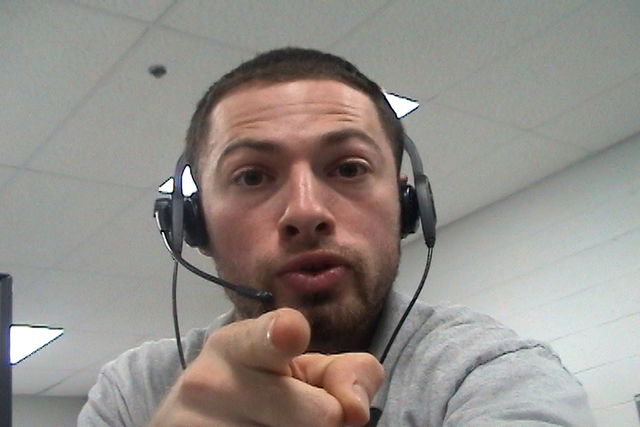

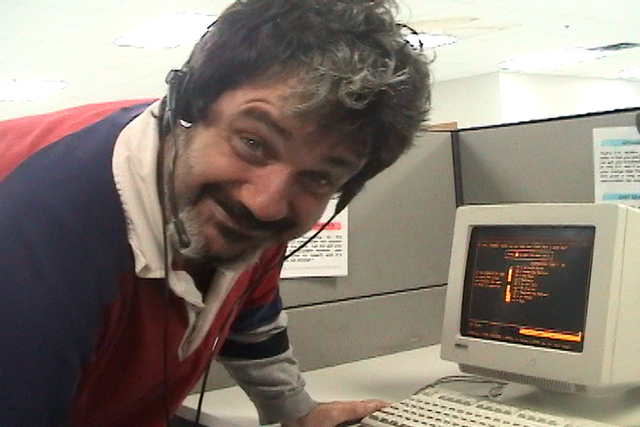

Lipman-Stern brought a video camera to work and filmed people smoking, drinking, snorting, and in some cases nodding out at their desks. There’s a clip of one telemarketer giving another a tattoo. In another, someone launches a giant metal sales trophy across the office like a shot put. “It was a fun place to be,” a former CDG office manager recalls. “It was like you was just going to a big-ass cookout, every f-ckin’ day.” Lipman-Stern uploaded the videos to YouTube, where they were mostly ignored. Meanwhile, he and his co-workers were encouraged to affect the drawl of a stereotypical police officer while making calls. In exchange for donations, CDG would send its marks FOP car decals that telemarketers implied would get them out of tickets.

What was happening out in the open might have been enough to cause a scandal. As we learn, the founders of CDG—two pairs of brothers, one of whom was in a truly awful Christian rock band—had been in and out of legal trouble since founding the company in the 1990s. But the worst was yet to come. CDG’s methods became even more brazenly unethical. And its business model, such as it was, spread across the country and throughout the industry. “Every other telemarketer who drives you crazy in the whole world is because of CDG,” one alum proclaims.

So Lipman-Stern and his pal Patrick J. Pespas hatched a plan to take down their employer from the inside. Those anarchic YouTube videos became the seeds of a documentary project that would, after nearly two decades of off-and-on investigative work, grow into Telemarketers. The revelations are outrageous. Beyond all the lying, bad behavior, and ruthless manipulation of the nonprofit fundraising model, Sam and Pat uncover convicted murderers shaking down terrified strangers for contributions they can’t afford and signs of corruption that reach up the ranks of many FOPs. A clumsy scam cooked up by four crooks, three decades ago, eventually intersects with some of the gravest contemporary threats: political polarization, dystopian misuse of artificial intelligence, the rise of PACs, legislators’ impotence in the face of police corruption.

The series is a feat of idiosyncratic citizen journalism, deadly serious at its core yet buoyed by the earthy humor of its subjects and creators. (The long list of executive producers includes the Safdie brothers, Danny McBride, and David Gordon Green.) But its heart and conscience, the ingredient that makes it more than just an unconventional exposé, is Pespas. Introduced as a “telemarketing legend” who excelled at peddling those useless decals even as his heroin addiction was conspicuous at the office, he becomes the embattled hero—a gentle, deeply compassionate guy with a keen moral compass. The courage he demonstrates in confronting various scammers and their enablers in the government is matched by his loyalty to Lipman-Stern and the other important people in his life. He may not be the most polished on-camera interviewer, but what he lacks in finesse, he makes up for in determination.

An archetypal David-and-Goliath story, Telemarketers also captures the strange moral inversions of our time. If cops are the good guys and criminals the bad guys, then why isn’t anyone besides Lipman-Stern and Pespas standing up against a scam that has swindled people across the country out of hard-earned money in the name of supposedly legitimate police charities? “I thought I was dysfunctional!” Pespas exclaims after one hair-raising discovery. Maybe, at one point, he was. But the truly destructive dysfunction in his corner of the telemarketing racket happened far from the chaotic call centers where Pespas earned $10 an hour making the real crooks rich.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com