Anielle Franco, Brazil’s racial equality Minister, never planned to be a politician. That was her sister’s thing. Five years older than Anielle, Marielle was passionate, decisive, and a born activist. In her campaigning for Rio de Janeiro’s Black and LGBTQ communities, she would “act first and worry later,” Franco recalls. “I was more timid. Because I had my sister there as a leader, I stayed on the sidelines.”

That changed in March 2018. A year after taking a seat on Rio’s city council, Marielle was assassinated—in retaliation, her colleagues believe, for her activism against police violence, racism, and corruption. The search for justice thrust Anielle, then 33, into the national spotlight. A competitive volleyball player and English teacher, she pivoted to full-time activism, launching a nonprofit in her sister’s name, at a time when far-right President Jair Bolsonaro, elected in late 2018, was taking a hammer to the human-rights agenda in Brazil. Her tragic family story, warm personality, and deft use of social media turned the once reserved Franco into an unlikely leader in Brazil’s Black rights movement.

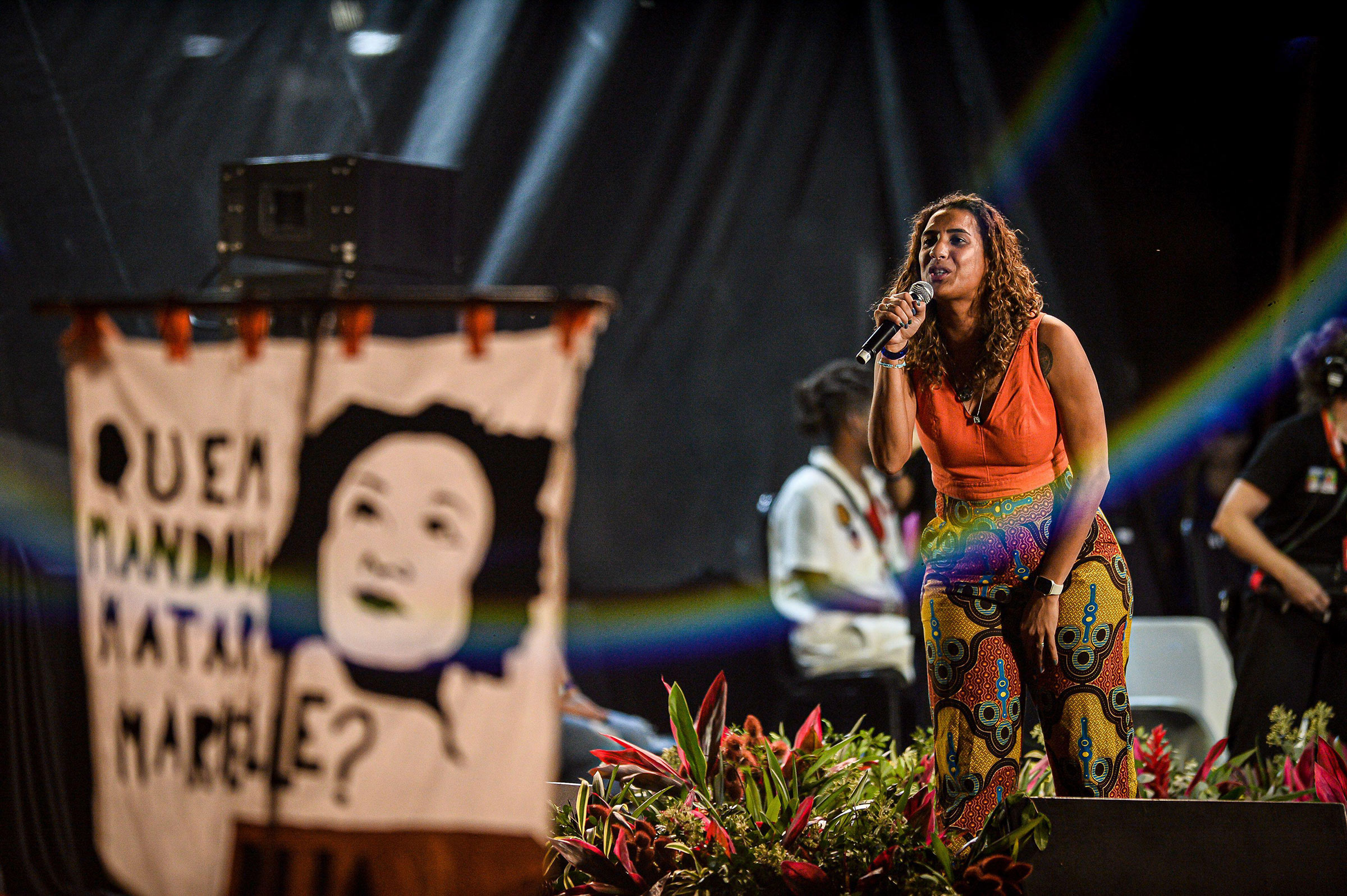

Now 38—the same age Marielle was when she died—Franco finds herself in a much more prominent position than her sister might have imagined, with a real shot at advancing their dream of a fairer Brazil. Franco took office in January as Minister for Racial Equality after leftist Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva defeated Bolsonaro in October elections. Franco’s job is to make sure Lula’s ministers and legislators deliver on his promise of equality for Black and mixed race Brazilians, who make up 56% of the population, and the country’s Indigenous and Asian minorities.

Read More: Brazil’s Most Popular President Returns From Political Exile With a Promise to Save the Nation

The stakes are high. Police killings hit record levels during Bolsonaro’s presidency as he championed shoot-to-kill tactics; 84% of the victims in 2021 were Black. In 2022, a deepening post-pandemic economic crisis triggered a 60% jump in the number of Black Brazilians experiencing hunger—almost twice the increase among white Brazilians. Bolsonaro also gutted budgets of the programs and agencies designed to help marginalized communities. “This was a political project that he was pursuing—to push aside everything that was for Black people, for Indigenous people, for women, for poor people, for LGBTQI people,” Franco says. “I’m just glad that we got to interrupt him.”

Though the election was tight, stopping Bolsonaro was likely the easy part. To undo four years of backsliding on equality, and ultimately to push further ahead with new policies, Franco will need the backing of other ministers and legislators, many of whom are unlikely to prioritize racial justice. She’ll also need to win support from a conservative-dominated Congress and from a deeply polarized public. (Franco’s planned Jan. 9 inauguration was delayed by two days after Bolsonaro supporters stormed Brazil’s congress, supreme court and presidential palace on Jan. 8 in the hopes of overthrowing Lula’s government.)

Franco says she can handle it. She remains a cautious person—but not one who can be shouted down, she says. “I lost my fear when they killed my sister. Now I fight for something much bigger than myself.”

Before she embraced politics, the most powerful force in the younger Franco sister’s life was volleyball. She was 8 years old, growing up in the Rio favela of Maré, when she started playing the sport, which is hugely popular in Brazil’s beach towns. At 16, she was offered a scholarship to play volleyball for two years at Navarro College in Corsicana, Texas. She ended up staying in the U.S. for 12 years (her teams “kept winning championships”). That gave her the chance to study English and journalism at two historically Black colleges—an experience she says helped shape her identity. “I didn’t realize how incredible it would be,” she says, smiling, “in terms of culture, representation, and my understanding of the anti-racism agenda.”

Read More: How Black Brazilians Are Looking to a Slavery-Era Form of Resistance to Fight Racial Injustice Today

Marielle’s killing—six years after Franco returned to Brazil for good—was an earth–shattering event for anti-racism advocates in Brazil. Many Black women had already been clear that Brazil was “a racist, sexist, unequal country,” says Bianca Santana, a São Paulo–based activist. But advances made under leftist governments in the early 2000s had left the impression that the country was stumbling toward equality. “Marielle’s murder told us something different: It doesn’t matter what you do, there is no place for you here. Even an elected official can be murdered,” Santana says. “It was a call to arms.”

Thousands protested in cities across Brazil in the weeks after the murder, demanding justice and an end to pervasive violence against Black people, women, and the LGBTQI community. Anielle Franco played a central role at those protests, along with Marielle’s widow Mônica Benício. (Two former police officers are in jail awaiting trial for the shooting, but investigations continue into who ordered the attack.)

To channel international attention on Marielle’s case into lasting change, Anielle founded the Marielle Franco Institute in July 2018. The nonprofit produced reports on incidents of racism, sexism, and political violence encountered by dozens of Black women politicians. The research, still widely referenced in Brazilian media, helped shatter a veneer of racial harmony that some still insist exists in politics.

Franco is most proud, she says, of the institute’s work to get more Black women elected—including successfully pressuring the electoral court to mandate that parties give Black candidates a fair proportion of campaign funds and airtime on television. A record number of Black women ran for local, state, or national office in 2022, and 29 were elected to Brazil’s Chamber of Deputies—up from just 13 in 2018. (That’s still less than 6% of seats, in a country where Black women make up 28% of the population.)

Now, with the power of the federal government behind her, Franco aims to fight a range of inequities that she says add up to “the genocide of the Black population.” One priority is combatting racist policing. Franco has already met with Brazil’s Justice Minister and offered to help design effective policy, and she wants to coordinate discussions with civil society, police, and favela residents. “We want to produce a working strategy with concrete actions. We can’t sit here speculating while people are dying.”

On some issues, Franco will need the support of Bolsonaro loyalists, who have falsely accused Lula’s government of stealing the 2022 election. “The first step is to understand who is willing to talk,” she says. “If we can get through to some people, it will make a big difference.” And she may be more successful than most, argues Santana, the activist. “Anielle has this very proper yet very warm way of speaking and doing politics. She believes in humanity,” she says. “That makes people want to listen to her.”

With four years left in her role, Franco has space to dream big. “I hope that Black people move into the place of protagonists in our society, and not just the front page of newspapers as victims of a genocide.” Only then, she says, can Brazil become “the happier place” that the rest of the world thought it was before Marielle’s killing and Bolsonaro’s presidency. “The country of samba, of soccer, of so many good things.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Write to Ciara Nugent at ciara.nugent@time.com