On June 2, with schools in the northern Brazilian state of Pernambuco closed because of the COVID-19 pandemic, Mirtes Renata Santana de Souza brought her 5-year-old son Miguel to work with her. Santana, 33, and her 60-year-old mother Marta both worked as maids for a wealthy white family: Sérgio Hacker, the mayor of the small town near the city of Recife, his wife Sarí Corte Real and their two children. The family were living on the fifth floor of a luxury tower block overlooking Recife’s seafront.

Around lunchtime Santana went out to walk the family’s dog. While a manicurist was doing Corte’s nails, Miguel said he wanted to find his mother. He kept running into the building’s elevators and Corte kept making him get out. But eventually, she let the 5 year old get in the elevator alone, and, according to CCTV footage, appeared to press the button for the tower’s top floor before the doors closed. (Corte maintains she only mimed touching the button and that it did not light up as it would have if activated). Miguel got out on the ninth floor. He then fell from a balcony, 114 feet, onto the ground outside the lobby where his mother and a building caretaker found him moments later. He died soon after arriving in hospital.

The tragedy has become a sensation in Brazil over the last month, as media outlets have breathlessly reported each twist and turn, from the details of the state police investigation, to emotional interviews with both Santana and Corte. After newspapers published an open letter from Corte asking Santana for forgiveness, Santana responded that it was “inhumane” to make such a request. “We know that she wouldn’t treat a friend’s son like that,” she wrote. “She acted like this with my son, as if he had less value, as if he could suffer any kind of violence for being ‘the maid’s son.’”

On July 14 Pernambuco’s public prosecutor announced he was charging Corte with “abandonment of a vulnerable person resulting in death”—a crime punishable by 4 to 12 years in prison. An aggravating factor in the case for the prosecutor, and for public anger, is that it happened during the pandemic. Santana was not meant to be working on the day her son died because state officials in Pernambuco had not declared domestic work—apart from caring for elderly or disabled people—as “essential” during its COVID-19 lockdown.

The case has become a lightning rod for anger about a wider form of social injustice in Brazil. It is still common for Brazil’s middle and upper class families to employ a full-time maid. The South American country has one of the world’s largest populations of domestic workers—more than 6.3 million, according to government figures from late 2019. Some 95% are women and more than 63% are Black, like Santana. Historians say this structure is a direct inheritance from slavery, which Brazil abolished in 1888—the last country in the Americas to do so. Domestic workers only achieved the same legal status as other professions in 2013 and advocates say they remain underpaid and routinely mistreated, with seven in 10 working informally.

Neither Santana nor Corte feel that Corte was racist towards Santana or her son, lawyers for both women tell TIME. But in the details surrounding Miguel’s death, activists see the dynamics of a country that has failed to reckon with how its history continues to shape the lives of Brazil’s 211 million people, 56% of whom are Black or biracial. “Many still insist there’s no racism in Brazil, because it’s so well structured that you sometimes don’t even perceive you’re suffering from it,” says Luiza Batista, 63, a Black former domestic worker and the president of labor union the National Federation of Domestic Workers (FENATRAD).

Miguel’s case has helped galvanize both Black Lives Matter protests against systemic racism, and a movement to strengthen protections for domestic workers during the pandemic. “When I heard about Miguel, I felt that our lives really don’t matter to those people,” Batista says. “We’ve always been treated differently, inhumanely. We can’t take it anymore. “

In the weeks leading up to Miguel’s death, the pandemic had already put a spotlight on systemic racism in Brazil. The first confirmed death from COVID-19 in Rio de Janeiro was that of Cleonice Gonçalves, a Black domestic worker. She had caught the virus from her wealthy boss who had recently returned from a trip to Italy, officials told Reuters. As in the U.S. and elsewhere, COVID-19 has disproportionately impacted Brazil’s poor and Black communities, including domestic workers, who tend to live in neighbourhoods on the outskirts of cities, meaning long, risky commutes and poorer health and sanitation infrastructure. A June report from national research institute Fiocruz found “enormous disparities” in COVID-19 mortality of different races and classes, with a Black person who cannot read four times more likely to die after contracting the virus than a college-educated white person.

Many of Brazil’s 26 states have imposed local quarantine measures to prevent the spread of the virus, limiting activity that is not considered “essential work”–despite resistance to quarantine measures from President Jair Bolsonaro. At least four states included domestic work in the “essential” category. Batista, the union leader, sees that designation as deeply unfair given the country’s slowness to extend labor rights to domestic workers, and the low pay they still receive (an average of just $168 a month in late 2019). “When we are asking society to value our work, it denies us rights,” she says. “But when it comes time to serve, society judges our work to be essential. It’s very incoherent.”

The official recommendation of the attorney at Brazil’s federal Department of Labor is that domestic workers should be allowed to remain home with “guaranteed pay” while COVID-19 containment measures are in place. But less than half of employers surveyed by research institute Locomotiva said they were doing this. Of those who employ a domestic worker on a freelance basis, with no contract, 39% had let them go, while 23% said their employees were still working as normal during the pandemic. For workers with a contract, 39% of employers said their employees were still coming to work.

Batista says some employers’ expectation that domestic workers continue doing their jobs is a reflection of “a culture of slavery, of servitude that persists” in Brazilian society. “People think, ‘if I’m paying that woman to work in my house, then she should be here, I don’t care about the risk.’” At no point do they look at that person with empathy.”

Corte’s lawyer, Pedro Avelino, says the case has nothing to do with racism or discrimination. The families were very friendly, he says, adding that Santana, her mother and her son all came to stay in Corte’s house in Tamandaré, the town where her husband Sergio Hacker is mayor, for two months during the pandemic, before returning to Recife. “Miguel was treated very well. The time they spent in Tamandaré was like a holiday for him, playing all day with [Corte’s] children, in the pool, playing musical instruments.” He points out Santana and her family stayed in the guest room, not the maid’s room—even though there is one in the house. He also says that in the Recife building, Corte’s son, who recently turned 6, is allowed to use the elevator alone.

And despite the debate about racism provoked by her son’s death during the pandemic, Santana, Miguel’s mother, does not believe it was related to “social inequality stemming from race”, her lawyer Rodrigo Almendra tells TIME. But Almendra, who is white, argues that structural racism is nevertheless at play, embedded in the social and economic dynamic between the two families. “It’s in a lack of care, it’s in a Black boy being left to wander a massive building while his mother walks a dog.”

For activists, the Miguel case is a clear distillation of the systemic inequalities that make life very different for Brazil’s mostly Black working class and mostly white elite. The building Miguel fell from was one of two luxury apartment blocks called “the Twin towers,” which have been the target of controversy and legal battles around overdevelopment in Recife. Though Santana worked in the wealthy couple’s private homes, according to Brazilian media, the website of the local government in Tamandaré listed Santana as a municipal employee, on the public payroll. (Corte’s lawyer declined to comment on this.) State authorities are investigating the claims and Hacker faces calls for impeachment. And, in April, Hacker publicly acknowledged that he had tested positive for COVID-19, while Santana and her mother continued to work for his family at the house in Tamandaré.

“There are so many elements of our past in this case, in the structures that [underpin] it,” says Bianca Santana, 36, a writer and activist in Sao Paulo. “If you time-traveled to Brazil today from the 19th century, the race relations would look very similar.”

Brazil’s domestic work culture is directly linked to its history of slavery, experts say. By the time Brazil officially ended slavery 132 years ago, it had imported between 3.6 and 4.7 million slaves from Africa—more than any other country in the Americas. But after abolition, authorities largely left former slaves to fend for themselves, according to Larissa Moreira, 28, a historian studying the central African diaspora at the Federal University of São João del-Rei in Minas Gerais. “There was never an effort to incorporate Black people into the labor market,” she says. “A Black person didn’t start to be seen as a human being just because they stopped being a slave.” With little education, and racism rife among employers, many free Black people remained in the same kinds of work they had done as slaves, sometimes even at the same farms and houses where they had been enslaved. For many, particularly Black women, domestic work was the only option. At the beginning of the 20th century, seven out of ten formerly enslaved people were domestic workers, Moreira says. Race and domestic work remained so closely intertwined in Brazil that newspaper ads from the early and mid-20th century explicitly seek “a Black maid for domestic work,” she adds.

Though a vital source of work for Black women, domestic work was long considered a second-class form of employment. Until 1972, it wasn’t registered with authorities, and employers weren’t required to sign a work permit (which had been introduced in other industries in the 1930s). It was only in 2013 that a law was passed to give domestic workers the same rights as other professions, including a working day limited to 8 hours, overtime pay and employer pension contributions. Even today, domestic workers say they struggle to make sure employers uphold those rights, with 4.6 million working informally, without a signed permit or on a freelance basis.

This slow progress on domestic workers rights was intimately tied to the way Brazil approached race after the abolition of slavery, Moreira says. Instead of openly reckoning with systemic racial inequality, in the late 19th century Brazil’s leaders put forth a new identity for the country as a so-called “racial democracy”—a community founded on the harmonious mixing of Indigenous, white European, and Black African cultures. At the same time political and cultural elites promoted a policy of “whitening” the population, arguing that Black people should have children with white Europeans and their descendants, producing generations of increasingly lighter skinned biracial Brazilians.

“As a result we have a different kind of racism than in the U.S., where white supremacy has been more explicit,” Moreira says. Racial inequality in Brazil is stark: white people make up 44% of the population, but hold 79% of seats in the senate and earn on average 74% more than Black or biracial Brazilians. “But still there’s this idea of closeness, of a [Black] maid being like part of the family. That’s perverse because it legitimizes abuses,” Moreira says. In the case of domestic work, she notes, that means “white bosses asking ‘Oh can you stay two more hours? Can you come on the weekend?’ And that extra work might not be paid, because it’s a family thing.” It was common, before the 2013 law, for domestic workers to live six days a week in tiny and often windowless “maid’s rooms,” and be at their employer’s beck and call 24 hours a day.

Domestic workers also suffer more violent abuses. Santana, the writer, says she grew up surrounded by stories of beatings, sexual abuse, child labor and more during domestic work, told by her mother, grandmother and neighbours in her favela neighborhood, and later by her students when she became a teacher in adult education. One afternoon in the 1960s when Santana’s grandmother brought her mother and uncle to her employer’s home, a man offered the children a bar of chocolate which turned out to be soap. “My mother still tells that story with such a deep pain, because it was a situation of so much humiliation, and so much cruelty, for a child,” she says. “This kind of work is the site of so much violence. It leaves scars.”

Abuses like those still occur. In 2016, Joyce Fernandes, a domestic worker-turned-rapper, launched a Facebook page “I, domestic worker,” sharing testimonies from domestic workers about their experiences. The page, which was adapted into a book last year, brims with stories of humiliating and exploitative behavior by employers. According to FENATRAD, reports of abuse have increased during the pandemic. They say many domestic workers have been pressured to move in with their employer’s families during the quarantine.

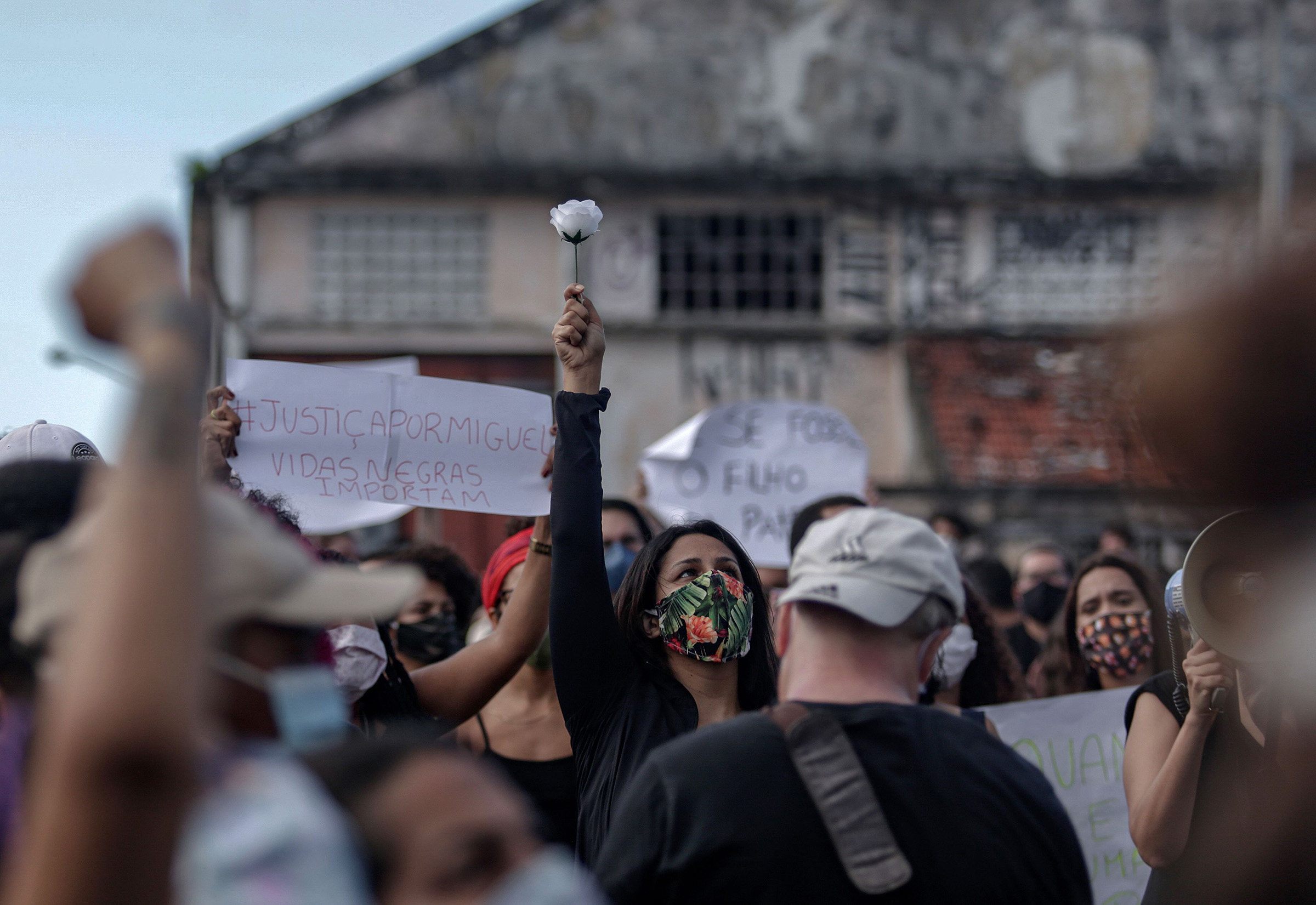

Some are trying to turn overlapping anger about Miguel’s death and the exploitation of domestic workers during the pandemic into concrete change. “Justice for Miguel” is now a rallying cry not only in Recife, at protests organized there outside the apartment building where he died, but also in campaigns urging the passage of a law to ban domestic work from being classed as “essential.” In the first week of July, a hundred lawmakers, public figures and social justice movements sent a letter to the head of Brazil’s chamber of deputies urging him to push forward a vote on the law, calling Miguel’s death “a mark of the urgency” to act.

From Rio de Janeiro, a group of eight sons and daughters of domestic workers are running a campaign, “For the Lives of Our Mothers,” calling for paid furloughs for domestic workers. Their petition has been signed by 130,000 people, and they have raised thousands of dollars for grants for workers who have been laid off by their employers during the pandemic. Similar small scale fundraising drives have popped up elsewhere, including a program for funders to sponsor a freelance domestic worker during the pandemic in Sao Paulo.

Juliana Frances is the daughter of a Black domestic worker and started “For the Lives of Our Mothers”. She says Miguel’s case has hit young Black activists in Brazil hard because for many of them, it feels personal. “It could have been me,” the 30-year-old says. “So many times as a child I went to work with my mother, with my godmother, or I was left alone [at home]. I crossed the road alone while my mother was cleaning someone’s bathroom.”

Working-class Black women are becoming less reliant on domestic work, though. Frances, the first in her family to go to university, is part of a younger generation who have benefited from the expansion of social programs in Brazil in the early 2000s. The leftist government of Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva used profits from a commodity boom to target poverty reduction and expand education access, says Mauricio Sellman, a visiting scholar of Latin American Cultural Studies at the University of Dartmouth. “For the first time, in 2018/2019, you had the first generation of university graduates that is actually reflective of the class and race of the general population.” Since Brazil’s lurch to the right under President Bolsonaro, and a series of economic crises starting in 2014, funding for these welfare programs has been cut.

For Frances, an equally important change lies in generational attitudes to Brazil’s deep-rooted structural racism. ”My friends and I discuss it all the time, but my mother’s generation was forced, culturally, socially, to keep their mouths shut, to accept this idea of “racial democracy,” which muffled the discussion,” she says. “So now when I speak to her about it, I can see she’s really uncomfortable.” Though Black people have been protesting and mobilizing against racism in Brazil for decades, Frances says the events of the last few months—the pandemic, Miguel’s death, and Black Lives Matter protests—have created a “revolutionary, unprecedented moment” for Brazil’s mainstream debate. “I think that in 2020, it’s the first time we’ve seen a lot of people acknowledging that yes, we are a racist country and we need to talk about it. That is fundamental.”

Santana, the activist from Sao Paulo, says there’s another reason that Brazil’s discussion on race is becoming more open. During and after his election campaign in 2018, Bolsonaro, the far-right president, made a series of explicit racist remarks about Brazil’s indigenous and Black quilombo communities founded by former slaves —undermining more than ever before the idea of racial democracy. In doing so, he “authorized” some white Brazilians to express racist viewpoints, she says. “That was important for exposing what people think and feel, and now we’re in an increasingly explicit conflict [about racism],” she says. “Now, it feels like we’re on the cusp of an explosion.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Introducing the 2024 TIME100 Next

- The Reinvention of J.D. Vance

- How to Survive Election Season Without Losing Your Mind

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Scams

- Did the Pandemic Break Our Brains?

- The Many Lives of Jack Antonoff

- 33 True Crime Documentaries That Shaped the Genre

- Why Gut Health Issues Are More Common in Women

Write to Ciara Nugent at ciara.nugent@time.com