On Jan. 6, 2021, Amanda Tyler watched the attack on the U.S. Capitol unfold with a growing sense of dread—and recognition.

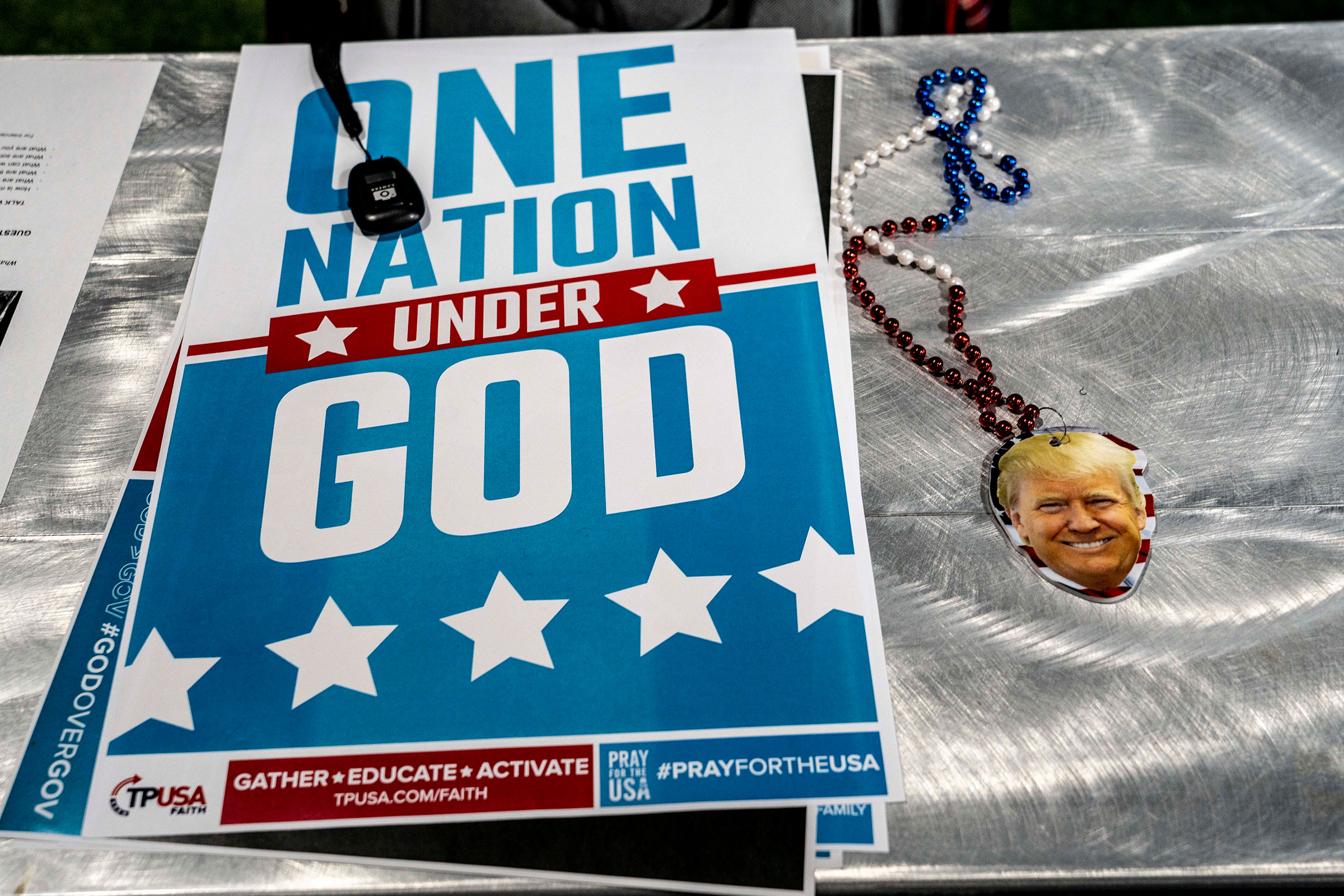

Like many Christian leaders, Tyler, the executive director of the Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty, immediately noticed the presence of religious symbols in the crowd. Large crosses were everywhere, carried by protestors marching to the Capitol and depicted on flags, clothing, and necklaces. Demonstrators held up Bibles and banners reading, “In God We Trust,” “An Appeal to Heaven,” and “Jesus is my savior, Trump is my President.”

Many of the people there that day cast the attack on the Capitol to stop the certification of the 2020 election as a biblical battle of good versus evil. Christian nationalism, a resurgent ideology that views the U.S. as a Christian country and whose proponents largely define American identity as exclusively white and Christian “helped fuel the attack on the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, uniting disparate actors and infusing their political cause with religious fervor,” Tyler testified on Dec. 13 at a House Oversight subcommittee hearing.

The hearing was the first time in recent memory that someone had been asked to testify publicly on Capitol Hill about the threat posed by Christian nationalism, indicating the growing alarm about an ideology that has become more pervasive and more mainstream since Jan. 6. Its influence was evident in several violent events since, including in the manifesto of the 18-year-old who murdered 10 Black shoppers in a supermarket in Buffalo, New York earlier this year.

“I’m really grateful that members of Congress are paying attention to how Christian nationalism overlaps with and provides cover for white supremacy, and how some of these extremists are being fueled by Christian nationalism, using it to try to justify their violence as being done in God’s name,” Tyler told TIME in a Dec. 15 interview.

Tyler, who says she sees Christian nationalism as a perversion of her faith, launched a grassroots effort called Christians Against Christian Nationalism in 2019 under the Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty, a national advocacy group she runs focused on religious freedom. She says she was inspired to start the campaign after a series of alarming events during the Trump era: she watched marchers at the 2017 white supremacist rally in Charlottesville, Va. shout “Jews will not replace us,” and then saw the ideology amplified by conservative television pundits and some lawmakers who echoed the language of religious war and professed the need to “take back” the country from those who threaten a white Christian nation. Christian nationalism also influenced the deadly violence at the Mother Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, South Carolina in 2015; the Tree of Life Synagogue in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania in 2018; and Chabad of Poway near San Diego, California in 2019, Tyler told lawmakers.

Tyler is aiming to bring together Christians from every congressional district in the country to help educate their communities to spot the ideology, which they see as a horrifying distortion of their beliefs, and give their communities the language to denounce and dismantle it. “We started it mostly in response to the increasingly violent iterations of Christian nationalism that we were seeing at houses of worship,” says Tyler, adding that Christians have a special responsibility to take action. But with the online conspiracies that motivated the racist Buffalo supermarket shooting, growing parallels in some corners of American political speech, and the deadly Capitol riot on Jan. 6, the problem has become more widespread: “We also felt the need to bring awareness to this larger ideology and how it was being promoted in maybe less violent ways,” she says, “so that everyone could understand how perpetuating these myths was contributing to violence.”

‘A high-tide moment for Christian nationalism’

The notion of restoring the country to greatness as a Christian nation has a long history in America. “Christian nationalism often overlaps with and provides cover for white supremacy and racial subjugation,” Tyler told lawmakers on Dec. 13. “It creates and perpetuates a sense of cultural belonging that is limited to certain people associated with the founding of the United States, namely native-born white Christians.”

While the ideology has deep roots in the country, the rhetoric fusing American and Christian identities has become increasingly popular in young far-right nationalist groups, which declare that “real” Americans are white Christians and hold a particular set of right-wing political beliefs. In recent years, this version of Christian nationalism has incorporated the language of the “Great Replacement Theory,” which claims that there is a vast conspiracy to replace white Americans of European heritage with non-white people.

Christian nationalism has gained steam among young right-wing personalities who have grown large followings. At a conference in March 2021, Nick Fuentes, 24-year-old white nationalist commentator, told an audience that America will cease to be America “if it loses its white demographic core and if it loses its faith in Jesus Christ,” emphasizing its role as a “Christian country.” Last month, he had dinner with former President Donald Trump at Mar-A-Lago, further raising his national profile.

Read More: Germany’s QAnon-Inspired Plot Shows How Coup Conspiracies Are Going Global

Some of this language has recently been embraced by prominent politicians, adding urgency to Tyler’s sense that Christian nationalism is embedding itself into more Americans’ political identity. “I say it proudly, we should be Christian nationalists,” Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene, a Republican from Georgia, declared this summer. Greene, who had previously come under fire for sharing a video in 2018 alleging that “Zionist supremacists” were conspiring to wipe out white people, doubled down by selling “Christian Nationalist” t-shirts. While politicians—particularly Republicans—have long made biblical references in stump speeches, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis has been criticized for using language that seems to echo Christian nationalist ideas. He used a Bible verse to suggest conservatives should “put on the full armor of God” in November, casting the midterm elections as a fight of God against the devil: “Stand firm against the left’s schemes,” he said. “You will face flaming arrows, but if you have the shield of faith, you will overcome them, and in Florida we walk the line here.”

Leaders who are flirting with the language of Christian nationalism “have merged their political authority with religious authority, and are using this language of Christian nationalism to justify political stances they’re taking,” says Tyler, calling this “a high-tide moment for Christian nationalism in our time.”

Christian nationalist violence

January 6 cast a bright national spotlight on Christian nationalism, as the movement’s rhetoric and imagery featured prominently in the crowd of people participating in the worst attack on the U.S. Capitol on two centuries.

News photos from that day showed people draped in Trump flags worshipping next to large wooden crosses; one cross with the words “Jesus Saves” written on it was paraded to the Capitol as the building’s defenses were breached. “It was clear the terrorists perceived themselves to be Christians,” D.C. Metropolitan Police Officer Daniel Hodges testified to a House Select Committee last year.

This level of religious fervor in service of a political—and ultimately violent—cause was shocking to many Americans, though experts argue it shouldn’t have been. “The riot was a pitch perfect performance of the kind of white Christian nationalism that has ebbed and flowed throughout American history,” Ruth Braunstein, a sociologist at the University of Connecticut who studies the movement, wrote in February 2021.

That same rhetoric has also led to deadly violence in other incidents over the past few years. The shooter who murdered 10 Black people in a grocery store in Buffalo, New York in May this year cited the broader language of Christian nationalism as justification for his actions. While he said he didn’t consider himself a Christian, he said he lived by “Christian values” and echoed the language of prominent white Christian nationalists espousing the “Great Replacement Theory.” He denounced people as “anti-Christian,” expressed concern for “Christian Europeans” being ethnically displaced by “traitors,” and defined “white culture” he said he was fighting to preserve as “based on Christianity.”

Tyler says she has been “overwhelmed” by the response to her recent congressional testimony, and believes there’s a growing group of American Christians who want to join her cause. “Someone responded saying, ‘This should be shown in every church this Sunday.’ And this is exactly how I feel as a Christian,” she says of her testimony being widely shared on social media. “So I think that there is a large segment of this population who are Christian who are horrified by the use of Christian nationalism to galvanize and justify violence.”

In the coming year, Tyler is hoping to use the focus on the issue to grow the grassroots national network to help other Christian organizations learn to notice the signs of Christian nationalism “in order not to be complicit with its spread,” and learn to address it. “To dismantle an ideology that’s so deeply seated will be a generational project,” she says. “But it’s one that’s urgent for our democracy and for the safety of the country.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Vera Bergengruen at vera.bergengruen@time.com