“Ours is the dark house with no lights.”

This is how Sammy, the protagonist in Steven Spielberg’s semi-autobiographical film The Fabelmans, identifies his Jewish family’s home as they pull into the driveway from a night at the movies in New Jersey. It’s December 1952, and the reason the house is dark, according to the logic of the 2022 film, is that the Fabelmans are Jewish: Against the backdrop of the eye-catching Christmas lights displayed by their neighbors, they light a single menorah in the front window to celebrate Hanukkah, the Jewish festival that commemorates the re-dedication of the Temple after a successful revolt against the Greek empire by a group of religious zealots, known as the Maccabees.

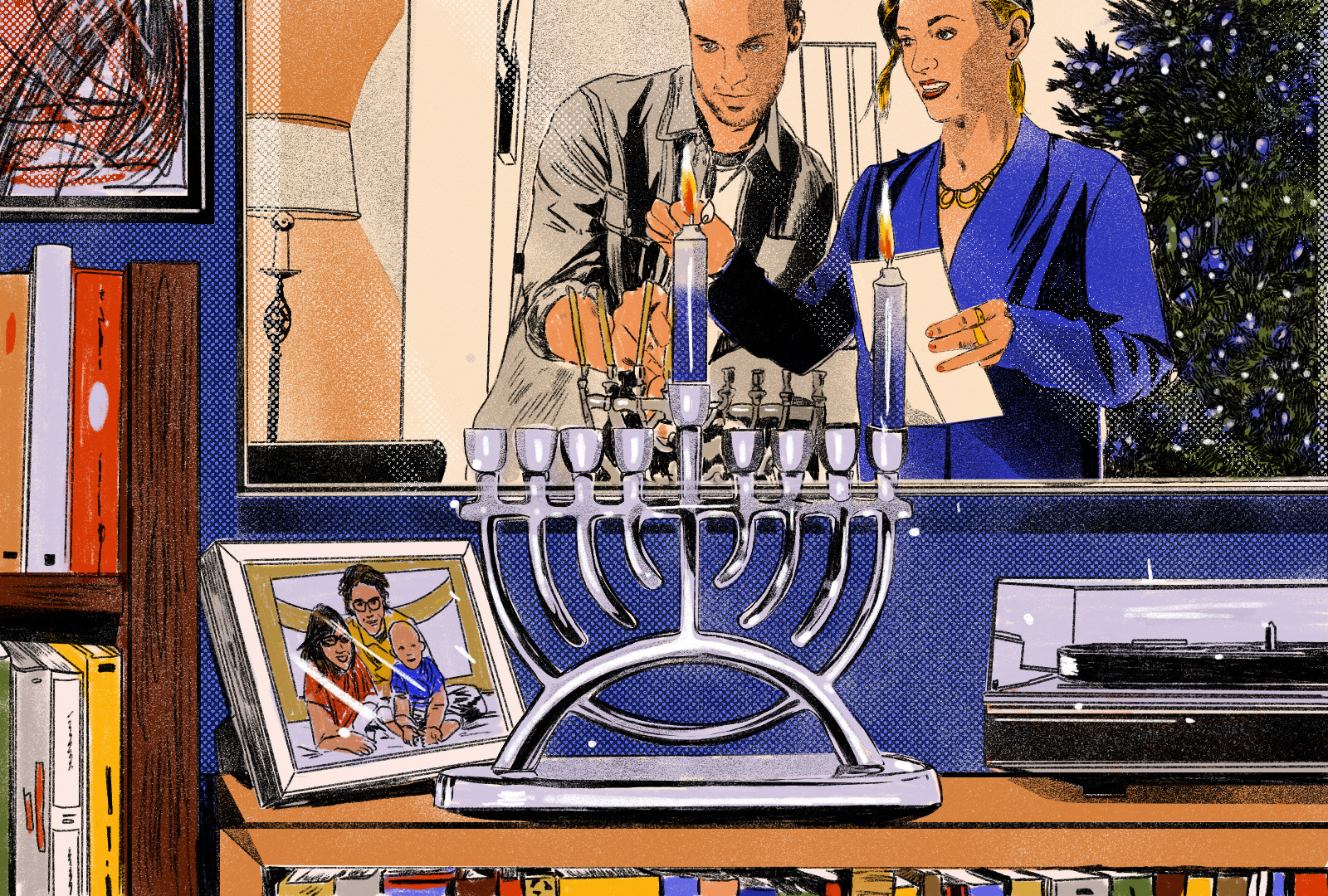

While in religious terms, Hanukkah is a very minor holiday, it has become the primary festival of Jewish visibility. Instead of spending December with dark, un-decorated houses like the Fabelmans, Jewish families today can distinguish themselves from their Christian neighbors by hanging a Hanukkah wreath on the front door, lining their walkways with dreidel lights, putting a giant light-up menorah on the lawn, decking the halls with Hanukkah garland, displaying Hanukkah dish towels in the kitchen, putting together a blue and white iced Hanukkah gingerbread house, and hanging Hanukkah ornaments on… something.

Read More: Steven Spielberg Waited 60 Years to Tell This Story

Outside the realm of home decor, Jews can dress themselves, their doll, or even their pet lizard, in traditional ugly Hanukkah sweaters with clever, totally Jewish slogans like “Oy to the world!”, send Hanukkah gift hampers and greeting cards to friends and colleagues, or even watch the latest Hanukkah holiday rom-com, which is basically a distillation of the other commercial elements of a modern Hanukkah. Much like “Oy to the World!”, it’s an essentially Christian format, with some blue paint and silver glitter splashed on to make it marketable to the 1.9% of the US population likely to find such a move appealing. It’s fairly obvious that most of this stuff is the sort of thing that non-Jewish corporations think makes them look inclusive by marketing to Jews, rather than being made by Jews, for Jews. But that doesn’t mean it’s inauthentic.

Let’s be clear: The Maccabees would have hated almost everything about this. The Books of the Maccabees record a highly partisan account of the Maccabean Revolt, which most current scholars believe is better understood as a civil war between Jews. Where the traditional account paints the opponents of the Maccabees as the invading Greek empire, determined desecrators of the Temple and suppressors of Jewish piety who martyred Jews caught observing Shabbat, a more clear-eyed historical analysis, such as that put forth by Sylvie Honigman, suggests that the main actors in the conflict were other Jews, who were interested in achieving economic and political advancement through alignment with the conquering empire and considered some laxity in ritual practice an acceptable price to pay. It is these Hellenizing Jews, rather than occupying Greek forces, who were the primary targets of Judah Maccabee’s military campaign—and the current incarnation of Hanukkah bears a far greater resemblance to their practice than to that of the Maccabees. There is a certain irony inherent in celebrating a successful military campaign against cultural assimilation by embracing cultural assimilation as long as it comes in blue, white, and silver instead of red, green, and gold.

Entire books—such as Joshua Plaut’s Kosher Christmas or Dianne Ashton’s Hanukkah in America: A History—have been written about the ways that the current practice of Hanukkah has developed. Mostly, changes in the observance of Hanukkah have been drawing it into closer alignment with Christian customs. These things tend to run in cycles: In the early 20th century Gershom Scholem’s family, like the majority of German Jews at that time, celebrated Christmas as a secular, national holiday, famously gifting him a portrait of Theodor Herzl for the holiday—an awkward parental gesture attempting to acknowledge his “interest” in Zionism. (Scholem was unimpressed, and familial estrangement soon followed.) The German Jewish immigrant communities of the United States also tended to view Christmas as a secular holiday, and participating in it as a way to showcase their integration into American culture. A number of the Christmas songs written by Jewish composers were composed in the late 19th and early 20th century, when this understanding of Christmas was fairly common.

However, as the 20th century progressed, concerns about assimilation increased, and communities began to search for ways to make Jewish identity both distinct and attractive. Adding a gift exchange—such as the one featured in Spielberg’s film—to Hanukkah was one strategy to decrease the relative attractiveness of Christmas, by removing Santa’s monopoly on gift delivery. The more prominent Hanukkah became as a Jewish observance, the fewer Jews embraced Christmas as harmless secular fun.

At the same time, non-Jews also had an interest in promoting Hanukkah as a distinctively non-Christian element within a secular “Holiday Season.” The middle of the 20th century was a period when the Supreme Court passed a number of important rulings on cases relating to the Establishment Clause, the First Amendment’s prohibition against laws “respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” In practice, this meant that exclusively promoting any one religion was a problem, but promoting religion in general (or ideas that were common to multiple religions) was permitted. In this context, the addition of a menorah to civic displays enforced the idea of Christmas as part of a generic, family-focussed “holiday season” which public institutions could endorse and promote without risking a violation of the Establishment Clause. The aggressive marketing of Hanukkah-themed versions of Christmas décor owes a great deal to the increased public visibility that resulted from this move.

Recently, Hanukkah editorials (much like the one you are reading right now) have begun to focus on what Gina Green has called the festival’s “darker side”. Michael David Lukas’s 2018 essay in the New York Times is characteristic of the genre: understanding himself as being dispositionally more aligned with the Maccabees’ assimilationist opponents than with the Maccabees themselves, Lukas questions “Why should I light candles and sing songs to celebrate a group of violent fundamentalists?” Arguing against Lukas, Rabbi Danya Ruttenberg highlighted the brutality of the religious persecution described in First and Second Maccabees, insisting that the “original meaning” of the festival can still be understood as a celebration of survival. Nevertheless, there is a growing consciousness of—if not quite yet a backlash against—the tensions between the origins of Hanukkah and its modern, commercial, assimilationist incarnation.

Read More: The Surprising Origins of 5 Hanukkah Traditions

That said, this debate over the “original meaning” of Hanukkah misses the point. Religion is not a question of “true” or “false”—“authentic” or “inauthentic”—which can be settled by such an appeal to origins; religion is defined, rather, by what people do. The meaning and the content of any religious observance changes over time. Hanukkah has become a major holiday because people treat it like a major holiday. More importantly, it is no more reasonable to expect Jews in 2022 to share the anti-assimilationist outlook of the Maccabees than it is to expect them to resume the practice of animal sacrifice—and, yes, there are some groups who would cheerfully embrace both. But they are very much in the minority, and what’s more, they have always been in the minority. Were that not the case, the Maccabees’ campaign against the Greek oppressors would not have needed to extend, as it did, to Jewish Hellenizers.

The story of the Maccabees presents the choice between fanaticism and extinction as a stark binary, but it’s not. Most people in history have not understood their lives as a choice between one and the other. Most of us live in the in-between, preserving our customs and culture, but not at the cost of complete isolationism, or human life. The ways that the story of Hanukkah is re-told today are a living reminder that the victories achieved by and through extremism are, at best, short-lived. Resistance to assimilation doesn’t always look like a pitched battle, or the one dark house on the street—sometimes it can be an unapologetically ugly sweater.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com