Mike Pence’s forthcoming autobiography takes its title, So Help Me God, from the oath he has sworn to abide by numerous times during his long career in public office. But as the Jan. 6 Committee winds up its investigation, with its next hearing possibly its last, the question of whether Pence will appear under oath to talk to that panel about the events surrounding the insurrection remains an open one. Negotiations about the possibility were still ongoing in mid-September, according to a Politico report; speaking at an event the last weekend in September, Rep. Liz Cheney said she still hopes Pence appears before the panel, of which she is the vice-chair. On Sunday, Rep. Pete Aguilar, also on the committee, said “those continue to be evolving discussions” and that he thinks it’s “important” that the panel hear from the Vice President.

But when Pence was asked about the possibility of testifying at a New Hampshire Institute of Politics’ “Politics & Eggs” breakfast on Aug. 17, he took a cautious stance. “I would have to reflect on the unique role I was serving in as vice president,” he said. “It would be unprecedented in history for a vice president to be summoned to testify on Capitol Hill.”

But the Senate Historical Office, Senate Library, and presidential historians and biographers clarify that it would not be unprecedented for him to appear. Throughout history, the legislative branch and the American public have been enlightened about both minor and significant issues by holders of the highest offices—including that of the vice presidency. As the late legal ethics scholar Ronald Rotunda wrote, “History shows that assuming the role of a witness is not demeaning or unprecedented for a President or former President…When a President or ex-President had knowledge relating to colorable charges of executive misconduct; he has made his testimony available.”

Read more: Jan. 6 Committee’s Plans in Flux as it Games Out Next Hearings, Final Report

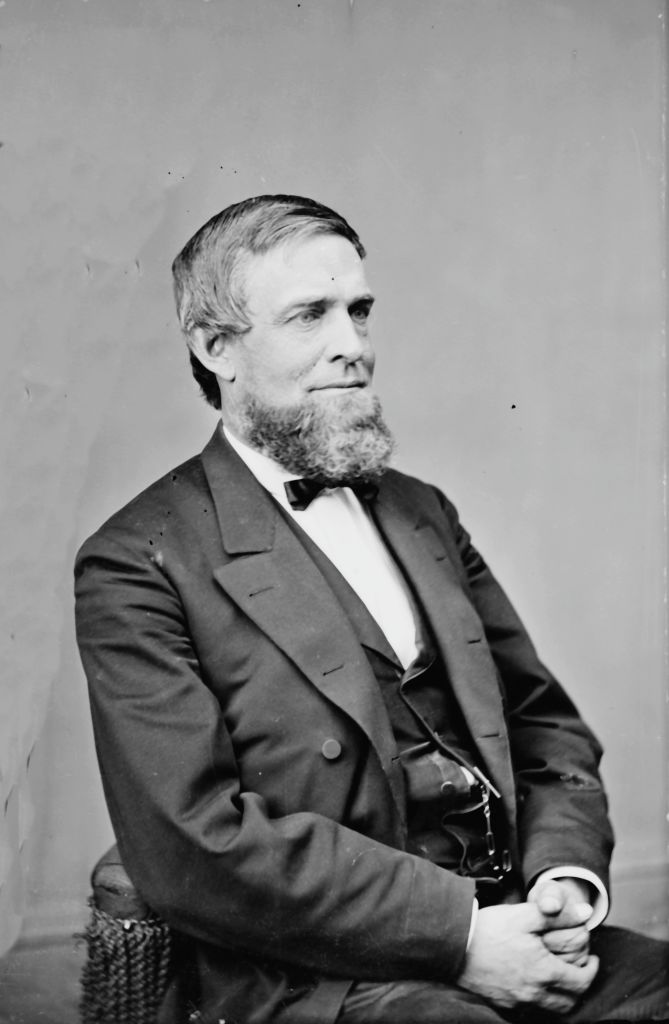

The first Veep to testify in a congressional hearing was Schuyler Colfax, a sitting vice president, who like Pence got his national political start as an Indiana member of the House of Representative. In January of 1872, Colfax, who became Ulysses Grant’s first vice president, became embroiled in one of the biggest political corruption scandals of the 19th century.

A blockbuster story in the New York Sun said government officials had taken cash and stock payments from a sham construction company, Credit Mobilier, in exchange for crafting policies advantageous to the building of the Union Pacific Railroad. Grant’s campaign for re-election was marred by sensational newspaper stories that implicated Grant’s outgoing vice president, Colfax, as well as several members of Congress.

“Smiler” Colfax, who had also served as Speaker of the House, denied the allegations in an 1873 hearing. His defense was shaky and new revelations—such as a ledger book that contained his name and transactions made with Credit Mobilier—brought weak explanations. Colfax would testify four times before a House Select Committee to try to clear his name.

James A. Garfield, then a fellow member of the House who had been under suspicion and had also given testimony, years before he would become president, described the experience in a letter to Colfax. “I have known no public proceeding so brutal and unjust as some of this Investigation,” he wrote. “Calm and justice may eventually prevail.”

Colfax, who had presidential ambitions, found his reputation severely damaged by his actions and he never held public office again. He embarked on a successful career as a lecturer and died en route to a speaking engagement after he walked nearly a mile in frigid Minnesota winter temperatures to get to a train depot.

Read more: Republican Congressman Adam Kinzinger on Where the Jan. 6 Committee Goes Next

Henry A. Wallace, Franklin Roosevelt‘s second vice president, also testified before Congress, appearing for the Senate Committee on Banking and Commerce in December of 1942, regarding his role as chairman of the entity responsible for the procurement and production of exported materials for the war effort. The testimony was described in the New York Times as related to a festering disagreement with Secretary of Commerce Jesse Jones over a bill to increase the lending authority of the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, run by Jones. The session ended with no action taken on the bill and by 1943 the rivalry had become a liability for the administration and Roosevelt dissolved the agency.

Wallace testified at least one more time after he left office. He appeared before the Senate Armed Services Committee in March of 1948 to oppose President Truman’s call for universal military training for all draft-eligible males. His downplaying of the threat of Communism did not resonate and in the presidential election of that same year, he received less than 3% of the vote.

Colfax and Wallace may be the only sitting or former VPs to have testified before Congress—the Senate Historical Office told TIME their research on this topic has not been exhaustive—but they are certainly not the only members of the executive branch. In fact, several Presidents have been in that hot seat. None other than Abraham Lincoln was the first president to give testimony before a congressional committee.

Despite being engaged in the conduct of the Civil War, Lincoln had personal reasons to clear his calendar for a visit to the Capitol. Lincoln met with members of the House Judiciary Committee to testify about the leak to the New York Herald of his annual presidential message. First Lady Mary Todd Lincoln was suspected to be the source of the leak and the president was anxious to clear her name, so he agreed to meet privately with members of the Judiciary Committee. The New York Tribune reported, “President Lincoln today voluntarily appeared before the House Judiciary Committee and gave testimony in the matter of premature publication in the Herald of a portion of his last annual message.”

Lincoln’s testimony and an article in the New York Tribune, which identified the culprit as the White House gardener, Watt, ended the investigation.

The next president to face a committee was Woodrow Wilson, who accepted an invitation from the Senate Foreign Relations Committee to testify about a peace treaty with Germany and the proposed League of Nations. In replying by letter to committee Chairman Henry Cabot Lodge, the president urged transparency and concurred with the committee’s desire that his testimony be made public. He offered, “In order that the committee may have a full and trustworthy record of what is said, I shall have a stenographer present.” The letter concluded, “It will be most agreeable to me to have an opportunity to tell the committee anything that may be serviceable to them in their consideration of the treaty.”

Wilson’s close aide and White House physician, Cary Grayson, attended the session and described what he witnessed in a letter to his wife. The president “showed that he was nervous—But he certainly handled himself magnificently. “

Grayson continued, “They went after him with numerous already prepared questions—but he simply had too much brains for them…Several Republicans would go off into the corner of the room—the East room—put their heads together and then come back and propound a question and the President would answer them as if he already had the answer written out for them.”

Even so, the Senate twice rejected the Treaty of Versailles, and the United States never joined the League of Nations.

On Oct. 17, 1974, President Gerald Ford voluntarily appeared before the House subcommittee on Criminal Justice to testify about his controversial pardon of Richard Nixon. Some historians cite it as the first formal, publicly broadcast, on-the-record appearance by a president in front of a congressional panel.

In his opening statement Ford said, “My appearance at this hearing of your distinguished Subcommittee of the House Committee on the Judiciary has been looked upon as an unusual historic event—one that has no firm precedent in the whole history of Presidential relations with the Congress. Yet, I am here not to make history, but to report on history.”

Ford assured Congress and the millions who were watching on television that there was no deal for a pardon and that his reason for the pardon was because “I wanted to do all I could to shift our attentions from the pursuit of a fallen President to the pursuit of the urgent needs of a rising nation.”

In a 1983 article for the Presidential Studies Quarterly, Stephen W. Stathis, who was an analyst with the Congressional Research Service, concluded that the former executive officeholders who provided congressional testimony shared a dedication to duty. “The common thread…is that they grasped, at least momentarily, a significant role never contemplated by the Founding Fathers, but one which they were willing to fashion in continued service to their country.”

Liz Cheney, the Wyoming Republican who is vice chair of the Jan. 6 Committee, seems to agree. Cheney said in an ABC News interview on Aug. 21, “I believe in executive privilege… But I also think that when the country has been through something, as grave as this was, everyone who has information has an obligation to step forward.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com