It was Aug. 8, 2021, and Bukayo Saka had every reason to fear the worst. Less than a month earlier, at the UEFA men’s Euro 2020 Final, he had been one of three England players to miss a penalty kick, crowning Italy as champions of Europe and unleashing a maelstrom of racist abuse online, because all three players are Black.

Now the 19-year-old found himself in London’s Tottenham Hotspur Stadium, a crucible of more than 60,000 howling soccer fans with burning hatred for his club team, Arsenal.

But then something momentous happened. As Saka left his seat to join the game in the second half, the entire stadium followed suit in a standing ovation, demonstrating unheard-of appreciation for an Arsenal player in more than a century of bitter feuding. “The fact that Tottenham’s fans are willing to do that for me shows that some things are bigger than football,” says Saka.

It’s a testament to the warmth Saka engenders, as well as the deep respect the soccer community felt regarding the way he dealt with the ugly events of July 11, 2021. The experience will toughen Saka, now 21, as the Qatar World Cup approaches in November, when England is one of the favorites to finally end its long trophyless run. The weight of expectation is overwhelming, and England has failed to win any of its past six matches. “We’ve been disappointed with some of our recent results, but we believe in our quality,” Saka says. “Everyone is just excited for the World Cup.”

Euro 2020 was a lesson in dizzying peaks and crushing lows. As a wave of optimism captivated the nation amid England’s first major soccer tournament final in 55 years, Saka was a talisman for the new positivity, encapsulated by a viral photograph of him grinning atop an inflatable unicorn in the team’s swimming pool. But everything changed after Saka was called onto the pitch late into the game alongside fellow Black teammates Jadon Sancho and Marcus Rashford, now both of Manchester United. All three missed their penalty kicks, prompting a torrent of racist fury on social media that London’s Metropolitan Police deemed “totally unacceptable,” leading to 11 arrests. In response, then U.K. Prime Minister Boris Johnson said existing stadium bans for fans who hurl racist insults at games would now also apply to online abuse.

Saka’s own reaction was to post a heartfelt missive on social media that ended poignantly with “love always wins.” “I can promise you this—I will not let that moment or the negativity I received this week break me,” he wrote, calling on social media companies to take greater responsibility. “I knew instantly the kind of hate that I was about to receive and that is a sad reality that your powerful platforms are not doing enough to stop these messages.”

Emile Heskey, a former England striker who suffered repeated racism during his 62 international appearances in the late 1990s and 2000s, tells TIME that Saka impressed him by handling the abuse following the Euro Final with “dignity” and “head held high.”

Such wisdom might seem surprising from a teenager under fire, but those closest to Saka weren’t shocked. Since the 1980s, young Black wingers have been derogatorily pigeonholed as talented luxuries, players who can score amazing goals but who are not to be relied upon in a pinch. Saka has blown up that racist shibboleth by demonstrating an innate tactical knowledge. He sees space before it appears and can predict teammates’ movements they haven’t yet thought of themselves.

Saka attributes his hard work and professionalism to his upbringing in a Nigerian immigrant family in the West London suburb of Greenford. Despite a multimillion-dollar professional contract, he still lives with his parents. “Anything I put my mind to, [my parents] pushed me 100% to give it my all, and to make sure I’m the best I can be,” he says. Raised Christian, he still reads his Bible every night before sleep, saying it provides “peace and happiness.”

Then there’s the fact that he’s rather good at soccer. His 20 goals and 19 assists in 106 Premier League appearances for Arsenal—where he was player of the year for the past two seasons—have cemented Saka’s place as an England regular on the right wing of the pitch. In September, he won the England men’s player of the year award. “He could play for any top European club—Barcelona, Bayern Munich, Real Madrid,” says Barney Ronay, chief sportswriter at the Guardian. “He’s that clever.” When Saka is not playing computer games—he claims to be the best gamer at Arsenal—he’s glued to his iPad, watching clips of the next opposition before every game in the hope of gleaning some weakness that might present an opportunity.

“He’s one of those that leads by example,” says Heskey. “He’s the first one running back, the first one trying to put a tackle in, but then he’ll be the first one driving out with the ball trying to cause havoc. It’s not been easy since at Arsenal, because he’s actually been the main man at a very, very young age.”

Leadership is not without burden. For many, the growing diversity in British soccer is an indication of a thriving society, sports being the ultimate meritocratic endeavor—if you’re good enough, you will play. The proportion of ethnic minority players in the Premier League has risen from 16.5% in 1992 to 43% today, although very few make the leap into management. Ten of England’s 26-man squad who reached the Euro 2020 final were Black. Saka’s genial demeanor has unwittingly made him both a “poster child” for an inclusive country and a mustering point for those who feel threatened or disturbed by the idea. “Saka’s been really politicized just for being a nice person, which seems ridiculous,” says Ronay. “He gets a lot of abuse on right-wing Twitter. You wonder about the pressure it puts on him.”

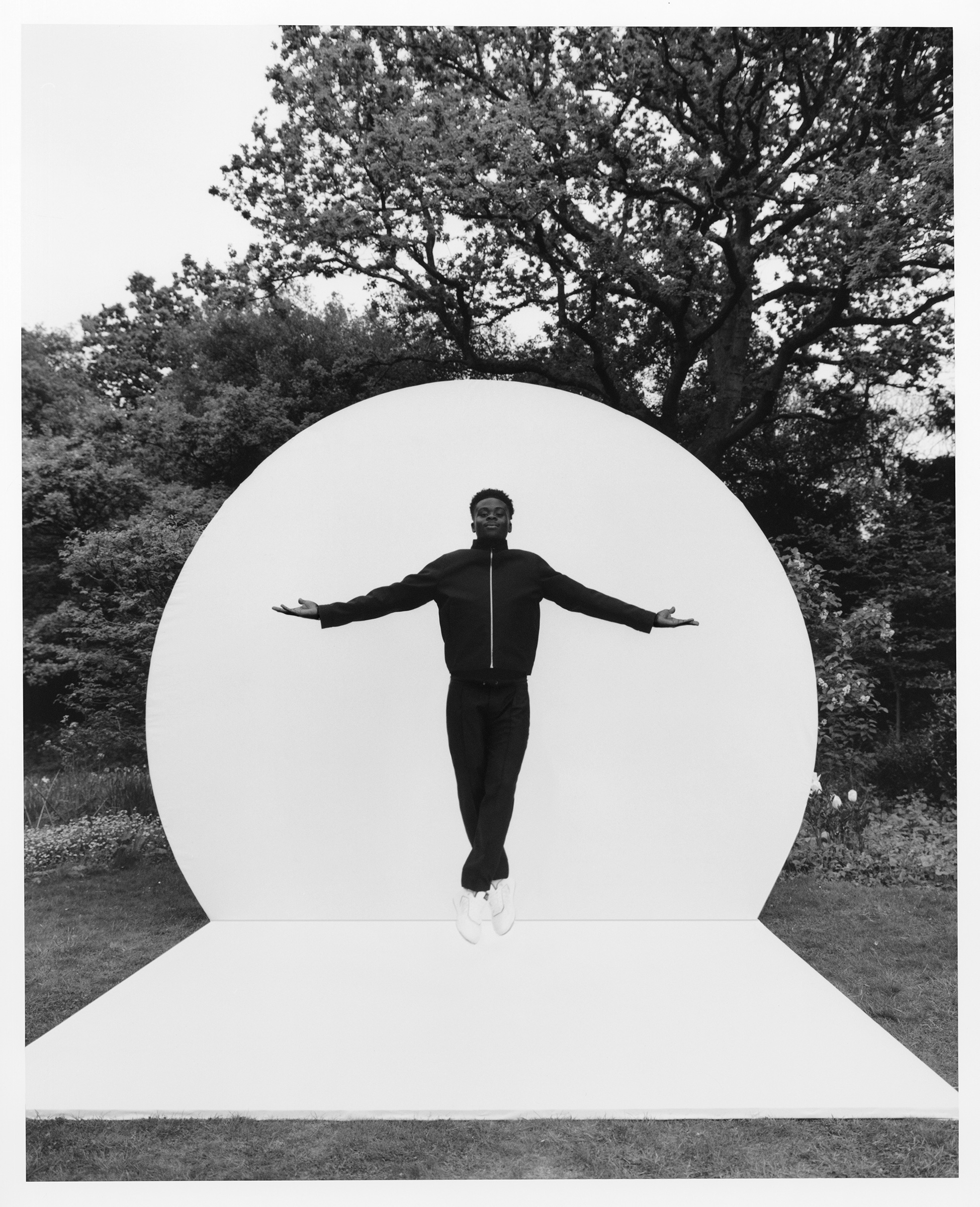

Get a print of the Bukayo Saka Next Generation Leaders cover here

The pressure will only increase as Qatar approaches. It will be the strangest World Cup of modern times. Because of Qatar’s blistering heat, the tournament usually held in summer is being held in winter—and halfway through European soccer’s domestic club season—for the first time. “It’s going to be a unique experience,” Saka says. “But it’s a new challenge, and I love challenges.”

Some challenges will be off the pitch. Millions of migrant laborers built an estimated $220 billion in new infrastructure and hospitality facilities for the World Cup, including eight stadiums, connecting rail and highways, hotels, plus an expansion of the airport. A survey of the embassies of India, Pakistan, Nepal, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka confirmed at least 6,750 migrant workers had died—typically from the heat and poor working and living conditions—since the tournament was awarded to Qatar in 2010. Saka has backed England captain Harry Kane’s call to use the national team’s platform to shine a spotlight on migrant labor abuses. “We’re all humans on the earth,” says Saka. “However we can help, we should.”

After the World Cup, Saka’s dream is to test himself on Europe’s grandest club stage of the Champions League. There’s little doubt that he’s destined to reach the pinnacle of the sport, and inspire a few people along the way. “I just want young people to realize that I was like them one day—with a dream,” says Saka. “There were some tough days, there were some good days, but you have to just keep going, keep dreaming, and keep believing.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Charlie Campbell at charlie.campbell@time.com