Ten years ago, when Susana Lujano and her husband Luis, first heard that they would receive Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), it felt like a godsend. Under the Obama-era executive order, they, and other young, unauthorized immigrants who were brought to the U.S. as children, could access work permits and enjoy protection from deportation.

But as DACA celebrates its 10th anniversary on Wednesday, the Lujanos remain mired in legal uncertainty. And it’s not just them anymore: their 5-month-old baby Joaquín is an American citizen. His future also depends on his parents’ ability to stay in the only country any of them have ever known.

While DACA was intended as a stopgap measure, Congress has failed to create a permanent pathway to citizenship, even as Republicans, arguing that former President Barack Obama did not have the authority to create such protections for young Dreamers, have repeatedly challenged the program in court. The result is that some 611,000 active DACA recipients, a generation long thought of as kids, are adults now, with jobs and homes and children of their own—and they remain in crippling legal limbo.

The average DACA recipient is now nearly 28 years-old and more than 184,400 are over the age of 30, according to December 2021 data by U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). There are now more DACA recipients over the age of 36 than there are under the age of 20. A 2021 survey conducted by the Center for American Progress, a nonpartisan policy institute, found that 33%—or more than 203,000—of DACA recipients have children of their own; 99% of those children were born in the U.S.

Read more: A Dreamer’s Life

Bruna Sollod, who was 21 when she received DACA, says that when she was young, the uncertainty of her immigration status was easier to manage. “I was a junior in college, it was okay for me to think in like two year increments,” she tells TIME. “Now that I’m a mom, now that I have a career that I really love, thinking in two year increments doesn’t work anymore.” Sollod is the mother to a 4-month-old boy, an American citizen.

Not knowing if you can keep your job, whether you’ll be deported, or if you’ll be able to raise your child in the country he was born changes the calculus of life, she says. “I’m angry that it takes so much suffering for members of Congress to realize that they have a job to do,” she says. “That makes me angry, and I don’t think I thought about it back then.”

The consequences of ending DACA will become more severe as the generation that received protections grows older, says Matthew La Corte, the government affairs manager for immigration policy at the Niskanen Center, a Washington think tank. “It isn’t just that some really bright high school student is not going to be able to go to the college they want or get the job they want,” he says. “Now, it really means breaking up families, it really means taking highly productive people out of the workforce, it really means the potential for the hundreds of thousands of DACA recipients who have U.S. citizen children, that their future is in peril.”

DACA in court

In it’s 10-year history, Republicans have challenged DACA and attempts to expand it numerous times in court. In June 2016, Texas was successful in blocking an Obama Administration executive order that would have provided protection from deportation to the parents of DACA recipients when it took its case to the Supreme Court. The Trump Administration also took steps to try to end the program. On Sept. 5, 2017, then U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced that the Trump Administration would end DACA, causing an avalanche of lawsuits trying to protect the program.

In a lawsuit brought in 2018 by conservative Attorneys General, lead by Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton, the states argued that DACA should be terminated because it was created unlawfully and that President Obama overreached his executive authority when he implemented the program. In July 2021, U.S. District Judge Andrew Hanen of the Southern District of Texas, sided with the states but ordered that DACA could continue while barring USCIS from processing new applications for people who qualified for the program.

Read more: Not Legal Not Leaving

The Biden Administration appealed the decision, and on July 6, the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals will hear oral arguments on the case. Many advocates and immigration experts believe the Texas case will likely make it to the Supreme Court.

When she first received DACA at age 18, Susana Lujano, who works full time as a practice assistant at a law firm in Houston, never thought that people would actively work to take the status away from her. The Trump years, she says, were the worst and hardest of her life. “At no point did I imagine it being so hard fought against,” she tells TIME over a Zoom call, while her mother feeds Joaquín in the background. “It was just blind hope.”

The odds of Congressional action

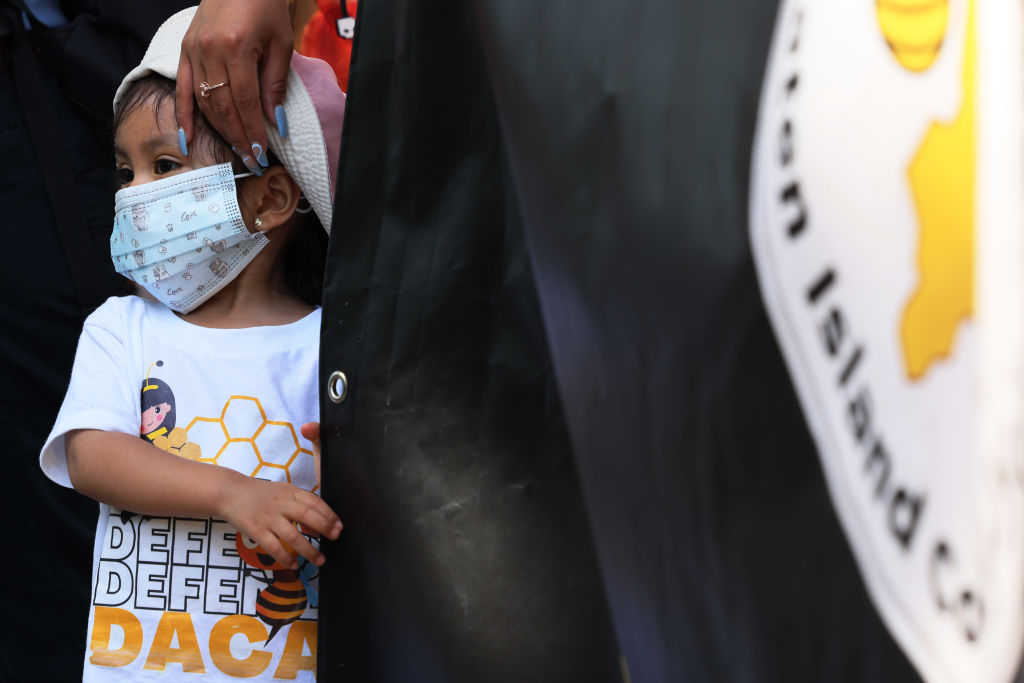

On Wednesday, crowds gathered in front of the Capitol building in Washington, D.C. and at rallies throughout the country to celebrate the 10-year anniversary of DACA and to call on Congress to create a pathway to citizenship for Dreamers.

Throughout the week, advocates met with lawmakers on the Hill, pushing Congress to create a pathway to citizenship for Dreamers. But such action seems unlikely, La Corte says. “While I encourage Congress to get its act together and pass legislation protecting Dreamers, I think we all need to be realistic about the unlikelihood of action,” he says.

According to a 2020 Pew Research Center survey, 74% of U.S. adults say they favor a pathway to citizenship for young people brought to the U.S. illegally as children. The vast majority, 91%, of Democrats or those who are Democratic-leaning, support permanent residency for Dreamers, while 54% of Republicans or those who are Republican-leaning say the same.

Read more: Read President Trump’s Full Statement on Rescinding DACA

Still, the issue of immigration remains highly polarized in American politics, particularly in an election year, and though a bipartisan group of Senators have been privately meeting to discuss possible immigration reform measures, action this term is not likely to happen. “There is an enormous lack of political will in addressing Dreamers this Congress,” La Corte says, unless something drastic like the Supreme Court terminating DACA were to happen. “Absent legal action which forces Congress’s hands, it is incredibly unlikely that Congress would be able to pass Dreamer protections in 2022.”

Sollod, who is now the senior communications and political director for United We Dream, an immigrant advocacy organization, says inaction is not an option. “A milestone like this, such as the 10th anniversary, really puts a lot of things into perspective,” she says. “What does the next 10 years look like? It cannot be like this again. It can’t be a repeat of the last 10 years.”

Should DACA be terminated, Susana says, and were she to receive a deportation order, she’d leave on her own before immigration officials could detain her. “I’m not waiting for them to come and take us,” she says. “I want us to leave with our head held high.” And yes, she adds, Joaquín would go with her.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Jasmine Aguilera at jasmine.aguilera@time.com