The story of the first encounter between Pablo Picasso and his muse, Dora Maar, has been much mythologised. It is said that Maar, aged 29 at the time, was seated alone at the popular cultural hotspot, Les Deux Magots, playing a game in which she stabbed a small knife between her fingers into the wood of the table. From time to time, she narrowly missed and her hand was covered with blood. Maar wanted to win the attention of Picasso, almost 30 years her senior, and this sadistic, sensational knife game worked. Whether the legend of their meeting is entirely true or not, it nevertheless epitomizes their emotionally charged, creative and tumultuous nine-year affair.

It’s through that turbulent, romantic relationship that Picasso’s famous portrait of Maar, as The Weeping Woman, is often viewed. But this muse’s story is one of more than just a crying woman, at the mercy of Picasso. It’s one in which she developed a strong anti-fascist worldview that impacted the older painter’s style and subject matter, resulting in one of the most powerful anti-war paintings in history.

Arriving in Paris at the age of 19, Maar studied at the progressive École des Beaux-Arts, Académie Julian and École de Photographie, where she developed an imaginative and atmospheric style of black-and-white photography. She soon established herself as a prominent photographer associated with surrealism, exhibiting at the 1936 International Surrealist Exhibition in London alongside Salvador Dalí, Man Ray, Eileen Agar and Paul Éluard. Maar also worked as a successful photojournalist and commercial photographer. By 1931, she had opened her own studio with the set designer Pierre Kéfer, taking on significant commissions for portraits, fashion magazines and advertising campaigns.

Maar’s talent as a photographer played a hugely significant part in her relationship with Picasso. Early in their affair, they worked alongside one another in her darkroom, where she taught him complex photographic processes, such as cliché-verre, meaning ‘glass picture’, which involves drawing handmade negatives on glass. Under her direction, Picasso used this technique to create a series of startling, unposed portraits of her.

It was during this early and artistically successful stage of their relationship, just one year after they had first met, that Picasso painted the infamous portrait: The Weeping Woman is unmistakably Dora Maar, with her distinctive, shoulder-length black hair, large, wide eyes, dark eyelashes and painted fingernails. “Dora, for me, was always a weeping woman,” Picasso notoriously said. He drew and painted her, afflicted by tears, over 60 times. But in many ways Picasso caused Maar to become a weeping woman.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

Outspoken and, at times, antagonistic, Maar was not afraid to stand up to Picasso, resulting in explosive arguments between them. His womanizing ways added to this tension. Picasso took great pleasure in creating competition between the women of his life, including Maar and another woman and muse he was involved with, Marie-Thérèse Walter, with whom he had a 2-year-old daughter.

Still, Maar’s tears should not be seen through the lens of her relationship, and abuser, alone. Far too frequently, patriarchal narratives have framed women as mere partners, privileging their romantic identities over all else. In the case of Maar, this reductive reading denies a more potent force at play—by the time that she met Picasso, the photographer had developed strong political beliefs that informed her art, and would soon impact her partner’s as well.

Like many surrealist artists, philosophers and poets during the 1930s, Maar had converted to left-wing politics. In fact, she became one of the Left’s most involved activists—a radical move for a woman at a time when women were still largely excluded from politics in France; they only gained the right to vote in 1944.

As the Great Depression of the 1930s hit hard, French politics became increasingly polarized, with citizens divided into two fronts: an extreme right-wing league or a left-wing who were united against fascism. Maar was amongst those who signed the Left’s ‘Appel à la lutte ’ (‘Call to the struggle’) manifesto; advocating for a social revolution.

Then, in 1935, Maar became involved in the Contre-Attaque group, who called for force and violence, rather than theoretical debate, in the fight against fascism; a passionate member, she not only signed their manifesto but operated their telephone line.

Maar’s deep commitment to left-wing ideology can be found in her social-documentary photography from the 1930s. Traveling to the outskirts of Paris, Barcelona and London, she portrayed laborers, the unemployed and children on desolate city streets and in the poorest neighborhoods. Her photographs evoke, above all, the humanity of those affected by the devastating Depression, inviting viewers to feel compassion with her subjects.

When the politically engaged Maar met Picasso, her left-wing views made a significant impact on him, as an individual, and as a painter. Increasingly sharing her sympathies, and following in the creative footsteps of Maar, Picasso became absorbed with the theme of human suffering in his work; and so it is through this lens that we must look at The Weeping Woman. We must also take into account his celebrated painting, completed just weeks before, Guernica.

Guernica is considered one of the most powerful and moving anti-war paintings in the world. Through this monumental mural, measuring over seven metres wide, Spanish-born Picasso depicted his outrage at the bombing of Guernica on 26 April 1937, by German and Italian warplanes, during the Spanish Civil War.

The brutal aerial bombing by fascist forces was carried out on market day. Many defenseless people, including children, had gathered in the streets of the small town in Spain’s Basque Country. Rather than focusing on fighter planes and armed soldiers, Picasso pictured the pain of these innocent victims, showing the true cost of war in human terms.

It was Dora Maar who found a studio large enough for Picasso to paint Guernica in. Through her left-wing network, she gained access to a space located on the Rue des Grands-Augustins, not far from Notre-Dame. The building was the former headquarters of the ‘Contre-Attaque’ group, of which Maar was a loyal member. Having heard anti-fascist speeches made here, she identified it as the perfect place for Picasso to embark on an epic protest painting.

Maar joined Picasso in the studio, allowing her to witness every stage of Guernica being painted over 36 days. Whilst Picasso worked, she photographed him. Picasso became her subject.

Maar’s images also highlight the immense influence that her black-and- white photography had on the artist. In stark contrast to his earlier colorful approach, Picasso used a monochromatic palette of black, white and gray to paint Guernica. His severe, photographic style created a nightmarish vision of fleeing and fallen human figures, animals distorted in agony, and hollow skulls, symbolic of death.

At the top center of the canvas, you can see a stark light bulb, blazing in the shape of an evil eye. This light illuminates the victims of war, exposing their suffering. Maar not only photographed Guernica, she also painted some of the hairs on the horse’s back, at Picasso’s request, and modeled for one of the women. At the extreme left of the painting is a mother, head thrust back, shrieking in grief, and holding the lifeless body of her dead child. This is one of the most devastating and unforgettable images within the painting. It is also the first time that we see Picasso painting a crying woman.

Read more: The Real History Behind Picasso’s Guernica

Just one week after completing Guernica, and in the very same studio, Picasso began The Weeping Woman. Maar recalls that he worked frantically, completing the canvas, for which she sat, in a matter of days, dating the finished work on Oct. 26, 1937. With this work, Picasso was continuing, and deepening, his exploration on the theme of human suffering: the screaming woman, fleeing Guernica, had become a weeping woman, engulfed in grief. Picasso’s Weeping Woman cries and cries, with no end in sight. Agony is etched into her face, defined by jagged lines; the handkerchief stuffed into her mouth appears like a shard of glass; and her black dress is the universal symbol of mourning. If you want confirmation that this painting, like Guernica, is an anti-war statement, take a close look at the woman’s eyes: you can see the silhouette of a warplane in place of each pupil.

The Weeping Woman is an evocation of overwhelming anguish caused by the atrocities of war. It encapsulates Maar’s compassion for human suffering, which she had photographed continually, and sympathetically, in her own work. In this portrait, it’s almost as if she is crying in grief at others’ pain.

Speaking out about his portrayal of Maar, Picasso revealed, “For years I gave her a tortured appearance, not out of Sadism, and without any pleasure on my part, but in obedience to a vision that had imposed itself on me.” That vision encompassed the photographer’s political sympathies and anti-fascist stance, which he had grown to share.

While The Weeping Woman can be read as a reflection of Maar’s distress within an abusive relationship, the muse herself refuted this intimate reading: “All [Picasso’s] portraits of me are lies. Not one is Dora Maar.” She meant more to Picasso than tears, and she knew it.

Resolute in her beliefs, articulate and persuasive, Maar was instrumental in encouraging Picasso’s political awareness, which culminated Guernica. She played an integral role in the creation of this epic mural—emotionally, creatively and even practically. Picasso’s depiction of the tragic suffering caused by war became yet more palpable in his next protest piece, The Weeping Woman.

Far from a forlorn, love-stricken muse at his mercy, Maar changed the trajectory of Picasso’s practice: she deserves credit for the cataclysmic role she embraced in his career. Behind The Weeping Woman is Maar’s compassion, intelligence and political activism, all of which profoundly inspired Picasso’s anti-war art.

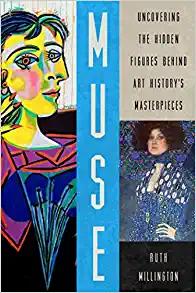

Adapted from Muse: Uncovering the Hidden Figures Behind Art History’s Masterpieces by Ruth Millington, available May 3 from Pegasus Books. Copyright © 2022 by Ruth Millington

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com