This article is part of The D.C. Brief, TIME’s politics newsletter. Sign up here to get stories like this sent to your inbox.

Here’s the thing about absolute denials: you can make them, but only once. The follow-up denial, usually offered as a caveat, a nuance, or even an update, simply doesn’t cut it. D.C. denials are a one-and-done proposition, which is why smart politicians usually send lackeys to make them or dodge the question altogether.

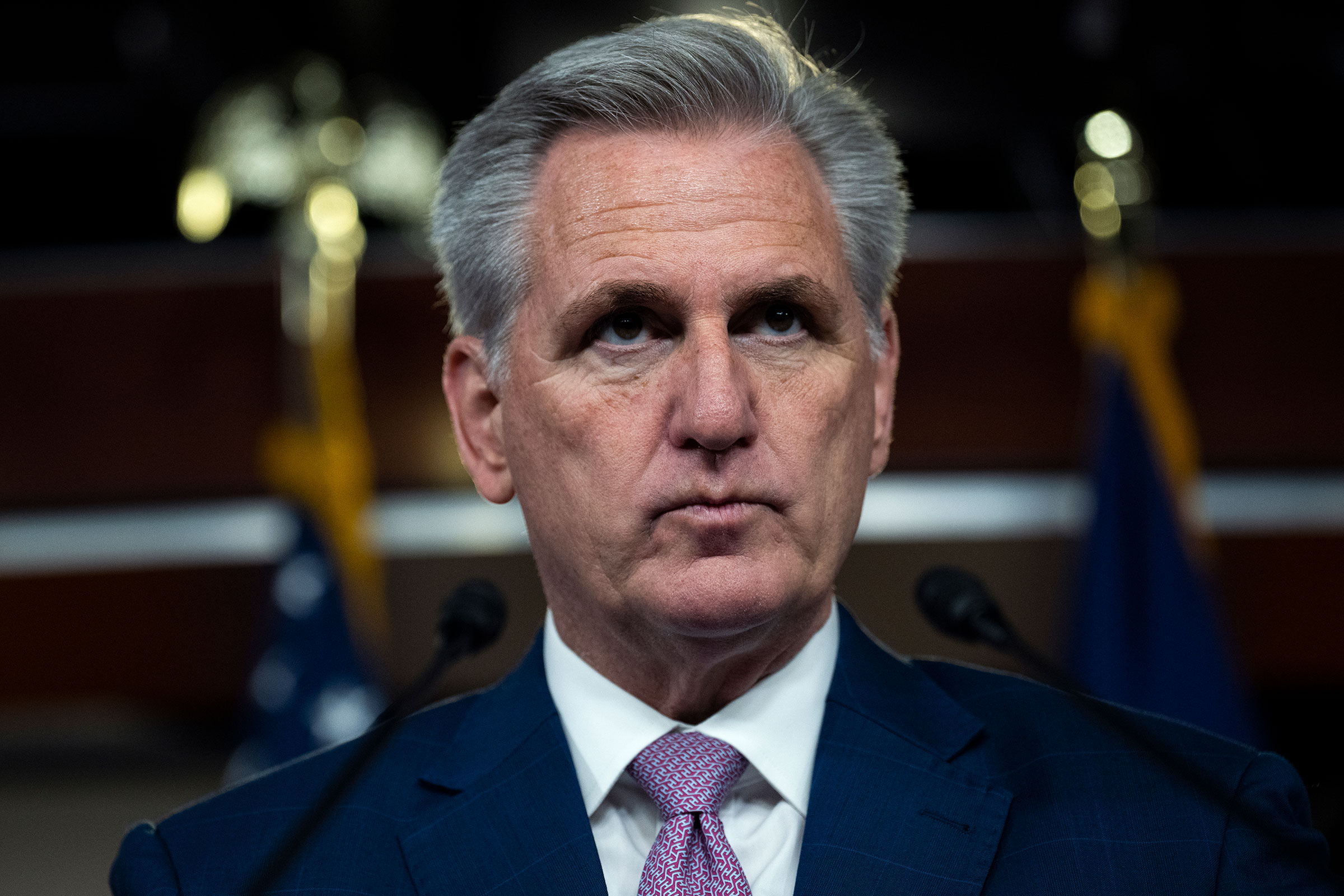

So when House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy released a statement in his own words on Thursday calling stunning reporting that he confidentially told colleagues in the wake of the Jan. 6 attempted insurrection he planned to tell then-President Donald Trump to resign, Washington took notice. McCarthy called the book excerpt from two New York Times reporters “totally false and wrong.” He didn’t hide behind his staff or issue a vague denial with wiggle room in the language. He was absolute in his certainty; he had never said “I’ve had it with this guy,” as the journalists published.

It was a double-dog dare if ever there were one in political journalism, right up there with Gary Hart challenging reporters to prove his affair with Donna Rice that ultimately killed his 1988 presidential bid. Nine hours after McCarthy took to Twitter to attack the reporting as “corporate media … obsessed with doing everything it can to further a liberal agenda,” New York Times writers Jonathan Martin and Alexander Burns were on Rachel Maddow’s MSNBC show. And they had the receipts—in this case, the actual audio recording from inside McCarthy’s close-circle call with just three of his top lieutenants.

The call, quite literally, was coming from inside the House.

McCarthy made two strategic mistakes. First, you never declare something entirely false unless you can prove it. In Washington, only the paranoid survive. Second, you never assume everyone on your team is rooting for you. That clearly was not the case back during the Jan. 10, 2021, call given at least one party—either a lawmaker or a staffer who may have been on the line—decided to preserve it for posterity.

McCarthy, who stands to finally claim the Speakership next year if Republicans can mount an even halfway competent campaign this November, now has his future in serious doubt. Yes, he wasn’t forthright, but character is seldom disqualifying on its own, especially in Washington. Unproven rumors of McCarthy’s personal life derailed his first bid for Speaker back in 2015, but he’s still the favorite to take the House’s top post this time.

More damning in his party, McCarthy dared question—however briefly—Trump’s supremacy after Jan. 6. On the recording of the Jan. 10 call among McCarthy, Minority Whip Steve Scalise, Conference Chair Liz Cheney and House Republicans’ campaign chief Tom Emmer, McCarthy is heard telling his Leadership team that he would call the White House and tell the President the impeachment charges against him in the House were going to pass. He then told his colleagues that he would tell the President it was time for him to resign, according to both The Times’ excerpt and the audio evidence.

Such doubt was briefly acceptable in the wake of the attempted insurrection and deadly riots. But the sentiment, of course, faded. That Jan. 10 call gave way to a Jan. 27 meeting—and accompanying photo—down at Trump’s Florida club between him and McCarthy. In the interim, McCarthy had clearly realized his hopes of claiming the Speaker’s gavel lie in Trump’s hands. If Trump didn’t go along with his candidacy—and the campaigns of a narrow handful of pick-up races Republicans need to return to the majority after four years of Nancy Pelosi’s second turn as Speaker—then McCarthy’s hopes of his own second race for Speaker would be dashed. (It wasn’t the first time McCarthy had resorted to unbelievable acts of sycophancy. Trump liked only certain colors of Starbursts, the reds and the pinks. McCarthy once sent Trump a jar of segregated candies after witnessing Trump’s predilections aboard Air Force One, which confirmed to McCarthy’s critics he would stop at nothing to climb to power.)

So after the New York Times article came out, McCarthy may have felt his future as Speaker depended on him denying he had pledged to suggest Trump’s resignation. But that could have been the wrong calculation. It’s now entirely possible McCarthy joins the likes of John Boehner and Paul Ryan as top Republicans cast out of the Speakership for not hewing to the most extreme—but loudest—voices in the GOP.

The one biggest unknown: what Trump demands as penance, if anything. It’s not logical that Trump would openly gun for McCarthy at the moment. But neither was Trump’s declaration he would destroy the 10 House Republicans who dared vote for his second impeachment. Trump remains agnostic that his primary picks at all levels could cost Republicans valuable seats. Predicting Trump is close to impossible, other than to know that he puts a premium on a counterpunch and often rejects empirical political evidence. His ego triumphs over calculation.

McCarthy’s initial denial hit just enough of the right votes of victimhood, red herring, and paranoia to maybe assuage Trump. But the audio gives McCarthy’s troubles teeth. And, unlike the audio released on the eve of the 2016 election in which Trump bragged about sexual assault, no one in the Republican Party is ready to give McCarthy the benefit of the doubt, so complete is Trump’s current hold on the party. A Trump endorsement, though, would keep McCarthy in the game. All eyes are now on McCarthy to see how far he’ll chase penance.

But his early full-throated denial is tough to unread. It is possible McCarthy, in the heady days after his office was sacked and his security detail left a colleague hiding on the Leader’s private toilet with a Civil War sword for protection against the Jan. 6 rioters, didn’t remember some details of that week. It’s also entirely possible that McCarthy this week panicked, realizing the consequences of even a momentary break with Trump, and did what came easiest, ethics aside: deny the accurate report. Either way, it was a bungle to hope no one could prove the denial. Just ask any number of fallen pols how that usually turns out.

Make sense of what matters in Washington. Sign up for the D.C. Brief newsletter.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Introducing the 2024 TIME100 Next

- The Reinvention of J.D. Vance

- How to Survive Election Season Without Losing Your Mind

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Scams

- Did the Pandemic Break Our Brains?

- The Many Lives of Jack Antonoff

- 33 True Crime Documentaries That Shaped the Genre

- Why Gut Health Issues Are More Common in Women

Write to Philip Elliott at philip.elliott@time.com