When Lena Kalandjian was 13 years old, she remembers struggling to recreate makeup looks she’d see in beauty tutorials on YouTube and Instagram. No matter how much money she spent on expensive products or time she spent practicing her techniques, her made-up face never seemed to measure up to those of the creators she was emulating. It made her feel stressed out and discouraged.

“I’d spend all my Christmas and birthday money on these products that were supposed to make you look flawless,” she says. “And they’d never look as good on me as they looked online.”

Kalandjian, now an 18-year-old senior at North Broward Preparatory School in Coconut Creek, Fla., says it took her years to realize that the finished looks she was seeing on social media were often the result of a combination of lighting, editing, and filters. “In real life, your skin is always going to have texture and imperfections,” she says. “There’s nothing you can do about that no matter how good of a makeup artist you are.”

One day, Kalandjian says, she started to understand the outsize impact that social media can have on young people’s mental health and the formation of their self-identity. That realization came from an unlikely source, an English class where students watched the Netflix documentary The Social Dilemma, which sheds light on the ways social media platforms manipulate and influence their users. Even more importantly, she realized that any problems she had with social media weren’t hers alone. Instead, they were part of the platforms’ design.

“In my younger teenage years, it felt like if you were addicted to social media, it was your responsibility to recognize that and log off when you were spending a lot of time online. It made me feel guilty about being on my phone all the time,” she says, adding that worrying about social media used to keep her awake at night. “But after seeing how the platforms are designed to maximize your usage, it was like, well, they never told us they were making it impossible for us to get off.”

Meta, the parent company of Facebook and Instagram, has rejected claims that it puts profits before the safety of its users. “As a company, we have every commercial and moral incentive to give the maximum number of people as much of a positive experience as possible on our apps,” a spokesperson said in a statement.

Since learning about why online content was wreaking havoc on her self esteem, Kalandjian has made it her mission to help other young people avoid the same fate.

Her school is just eight miles down the road from where 17 students were killed in 2018 at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High, a tragedy that vaulted concerns regarding student safety to the forefront of community attention. Kalandjian connected with Students Against Violence Everywhere (SAVE) Promise Club, an offshoot of gun violence prevention nonprofit Sandy Hook Promise that’s the umbrella for a national network of student-led groups dedicated to keeping young people safe.

Across the country, thousands of SAVE Promise Club members are working on safety for young people, a mission that’s increasingly intertwined with guarding them against the dark side of social media. And the issue is only growing more pressing. Last fall, whistleblower Frances Haugen alleged that Meta downplayed its own research on the harmful effects of its platforms on teens—effects that included eating disorders, depression, suicidal thoughts and more. Her testimony sparked months of news reports and Congressional hearings on social media’s impact on young people’s mental health and safety. Then, in early May, a 16-year-old girl filed a lawsuit against Snapchat alleging the company has failed to protect young users from sexual exploitation.

TIME spoke with three students, including Kalandjian, who have risen to helm SAVE Promise Club’s 13-person national youth advisory board and asked them how they’re feeling about how teens can help keep their peers safe online.

Making their voices heard

For Noor Soomro, who lives in one of the most culturally diverse school districts in the U.S, the turning point was Haugen’s revelation.

When Soomro, a 17-year-old senior at Lawrence E. Elkins High School in Missouri City, Texas, learned that Meta was aware of the toll its platforms take on young users’ mental health, she says it felt like a betrayal. She submitted testimony with the help of Sandy Hook Promise for the Senate’s October hearing on “Protecting Kids Online.” In it, Soomro detailed how it’s difficult to understand why social media companies would knowingly put young people in harm’s way. “Students already bear the burden of looking out for each other and taking care of one another,” she wrote, highlighting how young people often rely on one another for support when faced with difficult situations both online and off. “Social media companies and responsible adults should help us stay safe, not actively endanger us.”

In the months since, Soomro, who’s also part of a teen leadership program at her mosque, has started running peer-to-peer workshops that offer tips on maintaining a healthy balance between online and real life. “We talk about how stepping away and setting boundaries for yourself are really good starting points,” she says.

She says she’s seen a noticeable boost in school morale—she’s not only witnessed students putting away their phones to have more face-to-face conversations, but has also had people share how taking a social media break has improved their lives. “Students are more willing to connect with each other and aren’t relying as much on social media as their main form of entertainment,” she says.

That anecdotal evidence is backed up by professionals in the field. Shoshana Fagen, a clinical psychologist at Franciscan Children’s in Brighton, Mass., says that young patients she’s worked with have identified a similar correlation between time spent on social media and heightened feelings of emotional distress. “They’ve found that by taking a social media vacation or limiting the amount of time they’re spending on certain platforms, they’re able to have a better sense of self-worth,” she says.

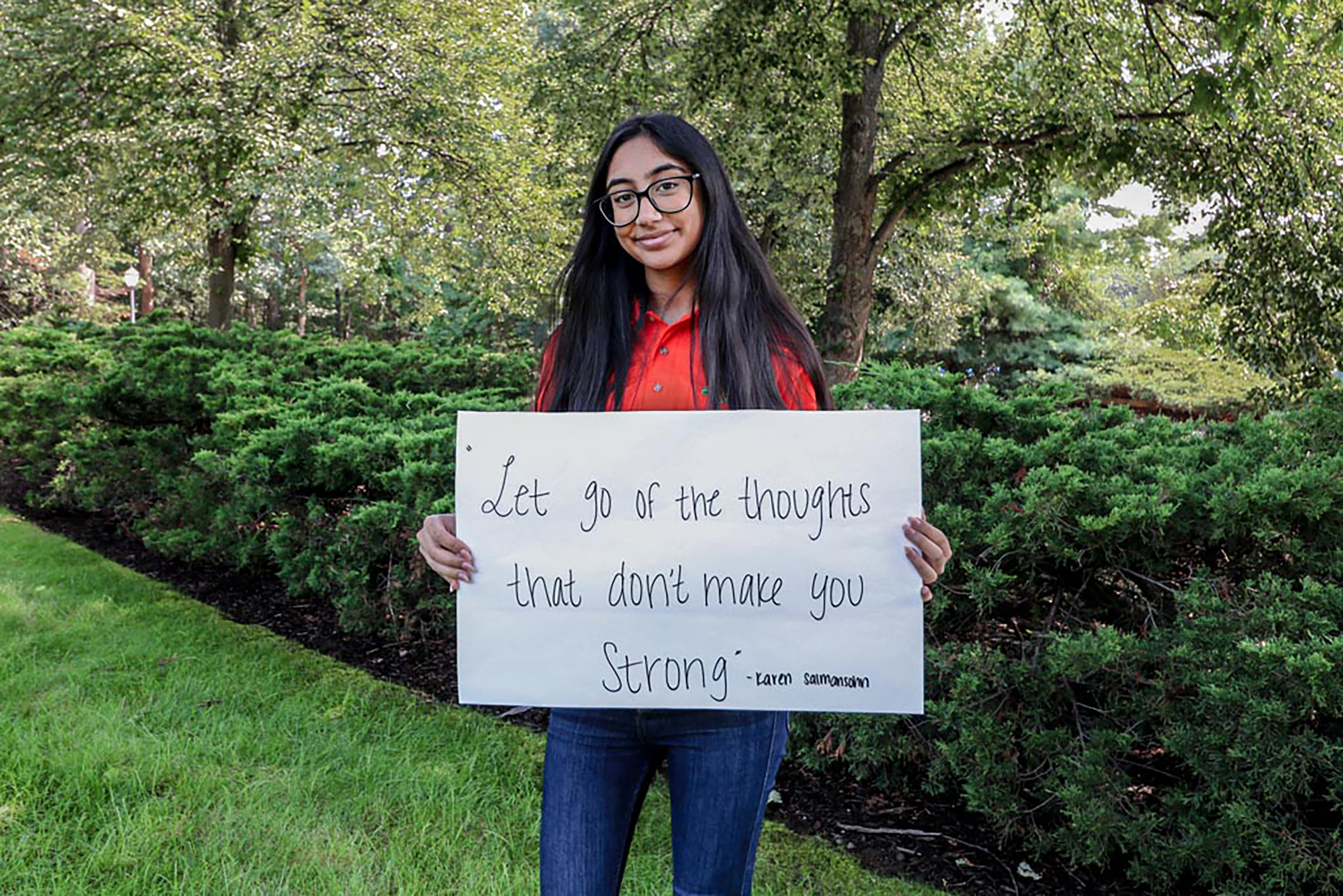

Aashi Mittal, a 17-year-old senior at Del Norte High School in San Diego, said her parents were wary of her using social media at too young of an age. So she waited until freshman year of high school to make her accounts—and soon found that the pressure to appear “perfect” online can be overwhelming. “We see this constant portrayal of life on social media where everyone’s always happy and going out with their friends and doing fun things,” she says. “It can lead to a very negative self-perception.”

Once she started using Snapchat and Instagram, she had to learn how to manage the feelings of inadequacy that would sometimes wash over her when she’d see posts from friends or influencers that made their lives seem perfect. That’s when she truly understood her parents’ hesitation. “A big part of self-care is creating a healthy online environment for yourself and taking breaks from social media when you need to,” she says.

Instagram has, in recent years, become a particular hotbed of photos depicting unrealistic and often unattainable body standards for young women. In 2019, the New Yorker published a story titled “The Age of Instagram Face” that explored how editing apps like Facetune and, more and more frequently, cosmetic plastic surgery procedures were giving rise to a “single, cyborgian face” among “professionally beautiful women” on the photo-sharing platform.

To contend with the harmful effects of online social comparison, Mittal, who founded her school’s SAVE Promise Club, has organized a number of mental health awareness programs with a focus on self-care through the lens of social media. Ironically, some of these programs are run through the same platforms exacerbating some of these issues. “It’s kind of a catch-22,” she says. “A lot of the information has to do with taking care of yourself by getting offline. But then I’m sharing it online.”

Why not just log off?

It’s not as easy as saying teens should just disconnect entirely. Not only has social media been compared to tobacco for how addictive it is, it’s also become an inextricable aspect of young people’s lives—especially since the start of the pandemic. While a 2018 report from the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry showed that teens were online for an average of nine hours a day, Common Sense Media reports that, in the last two years alone, the amount of non-school-related time 8-18 year olds spend on screens has increased by 17%.

“It’s this vicious cycle where if you don’t have social media, you feel like you should get on it. But once you’re on it, you feel like maybe you should get off it,” Mittal says. “It’s really hard to stop because the more people that are on it, the harder it is to not be and still feel like you belong.”

At Kalandjian’s school, Michelle Henne, a SAVE Promise Club advisor, history teacher, and cheerleading coach, says it’s obvious that social media dominates students’ lives. “They’re online from the minute they get up in the morning until after they’re supposed to be asleep,” she says. “If they don’t have their phones, they feel like they’ve lost all communication with the world.”

But part of the problem also lies in the fact that social media isn’t all bad. Fagen says that connecting with friends online gives young people an essential support system at a time when “peer interaction is vital to their social, emotional, and even ethical development.”

Despite the system working against them, the positive aspects of social media give Kalandjian hope that it can still be a “force for good” for young people. “Social media is going to be in our lives whether we like it or not,” she says. “So it’s important to know how to use it responsibly instead of listening to people who say, ‘Well maybe your life would be a lot easier if you didn’t use it at all.’ That’s not the solution.”

Since previous generations haven’t grown up with social media in the same way, members of older age groups sometimes don’t grasp the intrinsic role it plays in young people’s opinions of themselves and others. “You see elementary school kids already glued to iPads watching YouTube,” says Chris Nguyen, a SAVE Promise Club advisor and science teacher at Soomro’s school. “They have social media from such a young age and get more and more attached to it as they get older.”

Mittal says that parents and other adults need to be conscious of why things that happen online sometimes feel like the be-all and end-all of teens’ lives: “Adults don’t always understand why problems that seem small and insignificant, like getting a certain comment or not getting enough likes on a post, make us feel so bad.”

What’s next

In an attempt to rein in Big Tech’s power, lawmakers are moving to pass the Kids Online Safety Act (KOSA), a bipartisan bill that would create a responsibility for social media platforms to prevent harms to minors by providing them and their parents with options to protect their personal data, disable addictive product features, and opt out of algorithmic recommendations.

But with no guarantee that the Senate will vote to make KOSA law—and concerns swirling around whether the legislation would infringe on youth privacy—young people like Kalandjian, Mittal, and Soomro recognize that, regardless of what happens in Congress, their work needs to carry on. Frances Haugen herself is advocating for a broader youth-led social movement to build pressure from young adults for social media companies to reform their ways. She recently told the National Education Association that students should be leaders in demanding more accountability from tech giants.

For the teens who spoke with TIME, graduation is on the horizon.

Soomro is currently training juniors in her school’s SAVE Promise Club on how to run social media workshops once she graduates. “Doing this research and educating others has made me more aware of the time and energy I’m putting into social media and motivated me to help others set their own boundaries,” she says. “Hopefully, that can be my legacy and something that the school will continue to do.” In the fall, she heads to the University of Texas at Austin to study political communications.

While Mittal wants to continue to empower young people to have a healthier relationship with social media, she knows that what she’s already achieved is particularly impactful. “It’s really powerful to be in this age group myself and be able to speak about these things,” she says. “All the work that I’m doing right now is special because I’m living through it.” After moving cross country, she’ll start on the pre-med track at Williams College in Massachusetts this fall.

For Kalandjian’s part, she wants to weave this type of activism into her education and career from here on out. In addition to a recent TEDx Talk on online social comparison, she has also presented a social media webinar in collaboration with the National Center for School Safety at the University of Michigan.

There, she spoke to the audience of educators and mental health professionals about their blindspots when it comes to teens and social media. “We need to all be on the same page about how we can do better together,” she says.

Next year, Kalandjian will be attending Vanderbilt University to major in human organizational development. She says that she wants to channel her experience into building better institutions wherever her path takes her. “This is definitely something that’s going to stick with me for the rest of my life,” she says.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Write to Megan McCluskey at megan.mccluskey@time.com