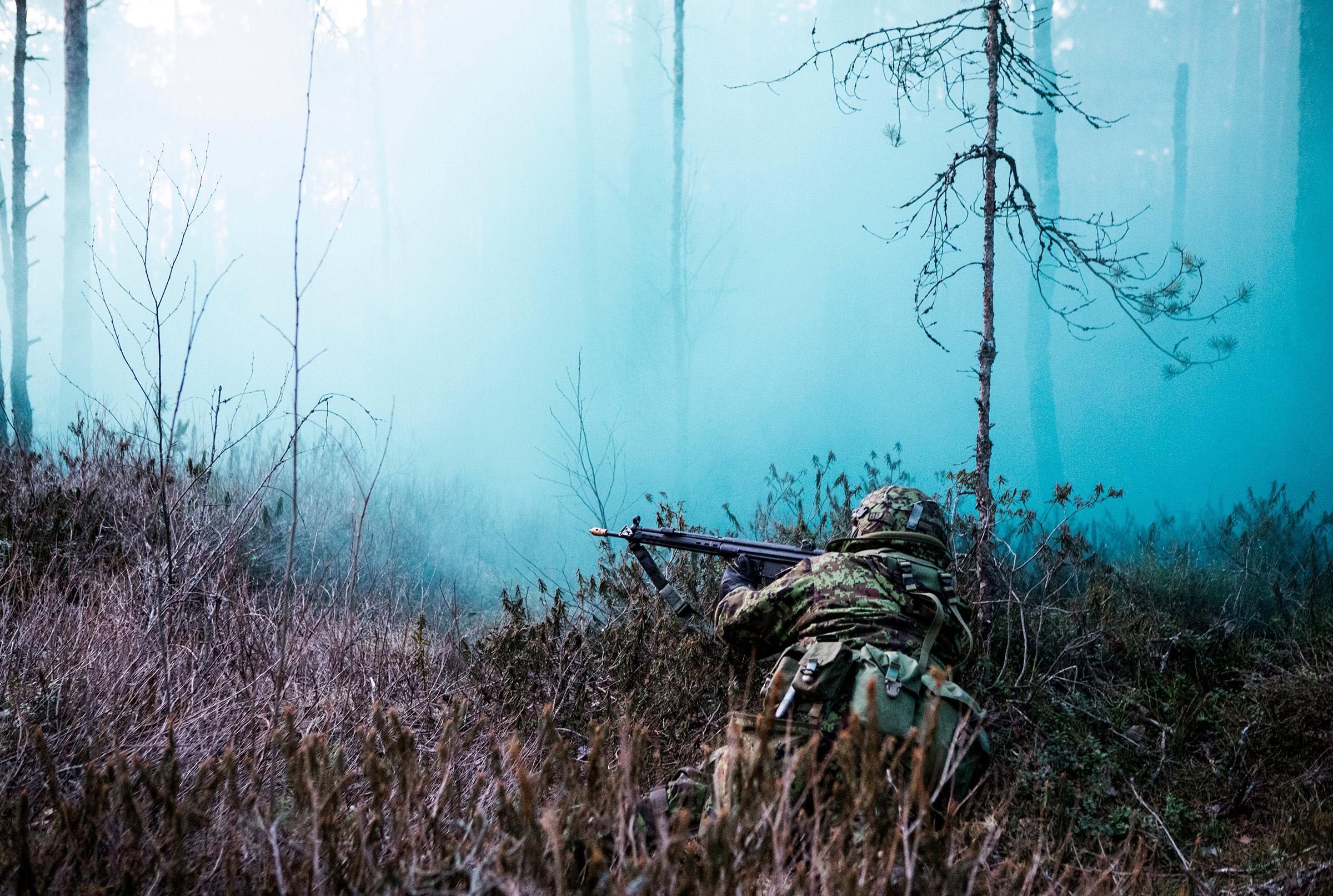

The ambush came at dawn. Moments before, the only sound in the frigid forest of Klooga, 40 km west of the Estonian capital Tallinn, had been light snoring coming from beneath a handful of camouflaged tarps. But seconds after machine-gun fire broke their sleep, several fighters erupted from their makeshift shelters and began returning fire. Flashes from their rifles illuminated the still dark woods, while blue smoke poured from a bomb intended to obscure the enemy’s path.

Within minutes, the battle was over. Although the outnumbered fighters did not manage to vanquish the opposing force, Kaia, an accountant who had left her baby at home that weekend, was pleased with the training exercise. “They did pretty well,” she said of the volunteers in the Estonian Defense League (EDL) she was helping instruct. “They stayed calm, and they held their ground.”

The Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania have been preparing to do the same. A shared border with Russia, and a painful history of Soviet occupation that began in the 1940s and saw the deportation and imprisonment of hundreds of thousands of citizens, spurred all three nations to join NATO once they regained independence in the 1990s. It has also led them to adopt a broad, society-wide approach to defense that has proved especially relevant more recently, as Russia has ramped up disinformation efforts in the region. Nowhere is that more evident than in Estonia, where 15,000 ordinary citizens like Kaia spend several weekends each year training in guerrilla warfare as part of the EDL. And since Russia invaded Ukraine in February, heightened fears that the Baltics could be the Kremlin’s next target have spurred thousands more to sign up.

“We are not conscripts. We are not regular army,” said Henri, 20, a participant in the Klooga “ambush” who works in sales. (Most members speaking with TIME preferred not to give their last names as a security precaution.) “We are ordinary Estonian men and women ready to put our blood on the line for every inch a possible occupier would want to gain of our land.”

Read More: ‘Everybody’s Waiting for Putin to Die.’ A Russian Businessman on the Hopes for His Homeland

Estonia takes protecting its population of 1.3 million seriously. Its defense budget is proportionately the third highest among NATO countries, and while there are only 7,000 active–duty soldiers in its military, it bulks up its defense and deterrence capabilities with reservists and with the EDL, which is the region’s largest volunteer force. At the start of 2022, it counted some 15,000 members, plus 10,700 in its youth organizations and Women’s Defense League, which provides support to the fighting units. That already added up to nearly 2% of the population, and since Russia invaded Ukraine on Feb. 24, the organization has received roughly 2,000 new applications for membership.

Most members are unpaid, though the Ministry of Defense funds their training and supplies weapons. “I truly believe that Estonians will grab a weapon or a tool against the Russian invaders,” says Lauri Abel, the ministry’s Under Secretary for Defense Readiness. A former commander of the Tallinn EDL, Abel sees the corps’ civilian status as crucial to its success. “They’re the link between the armed forces and society. They are everywhere, working in different companies. They carry the defense spirit to society.”

Even before the war in Ukraine, a full 57% of Estonians said they would be willing to participate in their country’s defense; some 80% approve of the EDL. It helps explain what induced Katlin, a 36-year-old who works in the financial sector, to spend a below-zero Sunday in late March in the snow, learning to make impromptu stretchers that could be used to haul wounded comrades out of the woods. “I wear heels five days a week. So this,” she says, gesturing to her heavy flak jacket and boots, “is a big difference. But I want the knowledge, and I want to be prepared.”

Preparation is at the heart of the league. New recruits spend eight weekends in basic training, where they learn to fire and clean weapons, to handle explosives, and a range of other survival skills. After passing a final test, they are allowed to keep their state-issued weapons at home. “I don’t know many countries in the world where the state entrusts its citizens to have combat weapons at their homes, just in case,” said one veteran member. “If we are suddenly attacked, I don’t need to go to a certain point to get my gear. I can just step out of my front door, walk 20 feet into the bushes, and then I’m dangerous.”

Read More: Inside the Historic Mission to Provide Aid and Arms to Ukraine

Against a conventional army with its large battalions and rigid formations, the EDL’s small, local units are intended to be much more agile. “One of our original principles is that you fight in the area you are from,” says Major Rene Toomse, who oversees the EDL’s training programs. “The point is that during peacetime you have time to learn all the terrain: you know where you can hide, where you can produce good ambushes—it’s your turf. Imagine what kind of leverage that gives you against an invading enemy. They have no idea where to go, and you know every inch.”

The EDL hasn’t yet had to test its abilities in a real conflict, but it collaborates with the Estonian military and with other NATO forces in war games and joint exercises, and is a major reason why researchers at the Rand organization consider Estonia’s total defense capabilities to be among “the most developed” of the Baltic states.

Read More: Meet the Lithuanian ‘Elves’ Fighting Russian Disinformation

That serves as reassurance in a country where many believe that should Ukraine fall, they will be next. After sitting in on the Klooga unit’s practice ambush, Major Toomse drove to a target range where a different unit was spending its Sunday learning to fire two-person antitank weapons called Carl-Gustavs. “If Russia thinks it can reoccupy Estonia or any Baltic country,” Toomse said, “it’s going to be a disaster for them.”

—With reporting by Simmone Shah/New York

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com