In October 1983, the Friars Club, that bastion of American comedy royalty, held a roast of comic legend Sid Caesar. Some 2,000 men laughed appreciatively, and among them was not one single woman. Mixed into the throng were some guests of club members, people who weren’t entertainment professionals but who were happy to spend a goodly sum for the experience of being among a constellation of comedy stars and listening to raunchy jokes for a few hours.

One of these was Phillip Downey, a slender, dapper, quiet, mustachioed fellow who was maybe a little pale for a guy from Southern California but who blended in like any other civilian at one of these wingdings. Nobody seemed to have made note of him when he arrived, when he got up to visit the restroom, when he left. But the next day, he was the talk of the Friars.

Phillip Downey didn’t exist. Underneath that wig and mustache and tailored suit and demure manner was Phyllis Diller, a comedy legend of more than two decades’ standing but someone who, simply by virtue of her gender, could not be admitted to the Friars as a member or be permitted to attend one of the club’s stag parties/roasts without resorting to subterfuge. “I’ve always wanted to eavesdrop,” she told the New York Post. “It was the funniest, dirtiest thing I ever heard in my life.”

Two years would go by before the Friars, as if shamed into it, made Diller the focus of a roast of her own, and another year would pass before they offered her membership in their ranks, making her the first woman ever admitted to their self-appointed comedy pantheon. It wasn’t an honor that she needed. For more than 25 years, Diller had been a household name across America and, indeed, the English-speaking world. But there was a great sense of justice finally being done as she was anointed by her peers and granted a place among them. It was as if not only a woman had earned a place in the highest ranks of American comedy but as if women in general were seen as deserving of such recognition.

Diller had broken ground by attending a Friars roast, if in disguise, and by carrying on in her craft and career until the Friars had no choice but to acknowledge her as one of their own. But then, Diller was one of a handful of women in comedy who had broken ground, blazed trails, knocked down doors, and made careers and legends for themselves regardless of the opinions of men. As in so many aspects of her career—indeed, in having a career as a comedian at all—she simply would not be denied.

That pretty much sums up the history of women in stand-up comedy, particularly the early history. They worked alone for the most part, both in the sense that they were almost all solo performers and in the sense that, in many cases, they didn’t know about one another or see one another as doing the same thing as themselves. They faced the indifference, puzzlement, nay-saying, and sometimes enmity of agents, managers, impresarios, audiences, critics, fellow performers, even their families. And yet they persisted, making their way ever farther and higher, if only incrementally, and clearing space for the women who followed them in the curious business of making people laugh for a living.

Today you look around the landscape of comedy and you see women ascendant, if not preeminent—women of all types, styles, ages, sensibilities. Today we have women doing comedy specials on streaming TV and headlining Las Vegas show rooms and moving from comedy clubs and podcasts to movies, sitcoms, talk shows, and book deals.

Today we have Amy Schumer, Sarah Silverman, Tiffany Haddish, Hannah Gadsby, Ali Wong, Mo’Nique, Rita Rudner, Tina Fey, Whoopi Goldberg, and Margaret Cho, among others.

It’s indisputable: there has never been more—or, arguably, better—comedy by women.

Maybe that’s why it can feel so absurd to recall a day when this once seemed impossible, when women were deemed unsuited for stand-up comedy, when the very idea of a female comedian seemed, to the eyes of the men who ran show business and to most audiences, to be a joke in and of itself.

But that was the truth of it. From the days of vaudeville until the dawn of color TV, a funny woman who wanted to tell jokes was faced with a brick wall—and not the kind you stood in front of at an improv comedy club. Female comedians were not only rare, they were actively discouraged. To arrive at an age when women stand-up comedians would be considered a normal thing, American culture and American show business had to metamorphose, sometimes in sync, sometimes leapfrogging each other.

Some of the struggle had to do with the very nature of stand-up itself. To speak of stand-up comedy is to speak of a very specific art form: the solo artist, armed only with a microphone and a store of wit, energy, jokes, and nerve, facing an audience. The stand-up comedian must be funny, most of all, but also fresh, original, relatable, economical, rhythmic, topical, timely, and adaptable. A stand-up act requires the approving response of an audience several times a minute. And a stand-up is, by convention, subject to the harassment of a bored or unamused audience or, indeed, any individual audience member.

All of these qualities of the art could seem, to someone steeped in antiquated and patriarchal ways of thinking, to be somehow “inappropriate,” or “unbecoming” for a woman, somehow “unladylike”—characterizations so absurd and offensive in and of themselves that merely typing them feels like succumbing to the most thick-skulled sort of misogyny. But prior to the spread of feminism in the 1960s, these were the dominant notions in the minds of the gatekeepers of show business and the audiences whom they served. A woman alone on a stage was expected to be pretty and to sing, maybe dance. If she did comedy at all, it was with a man or as part of an ensemble.

Never in these earlier days were funny women permitted to be women. For women to be accepted as comedians, they had to be constrained or distorted in such a way that the womanhood was bled out of them. They could be ditzes, cute but featherheaded in the vein of Gracie Allen, a brilliant comedian who worked for decades alongside her husband, George Burns. Or they could infantalize themselves outright as the great vaudevillian Fanny Brice did when she adopted her Baby Snooks persona.

They could act older than they were, as the comedian Jackie Mabley did in the 1940s, calling herself “Moms” and affecting the demeanor of a woman decades older than her actual 40-odd years. Or they could act foolish and rustic, as the college-educated Sarah Ophelia Colley did in her late twenties when she adapted the persona of a sunny, wide-eyed, man-crazy country gal whom she named Minnie Pearl. But what they could not do was walk out on a stage looking like an ordinary woman from anywhere in the world and talk in plain, comic terms about the things that people like them—that is, other ordinary women—might recognize as true and funny: husbands, children, housework, or any number of the quirks of everyday life that affected men and women equally but which show business and popular audiences seemed to think that only men could address. If they wanted to be funny, in short, they had to, in some way, deny their womanhood.

Ironically, it was the emergence of stand-up comedy as a distinct art form that made it possible for women to find wide acceptance as comedy stars.

At the start of the 20th century, vaudeville presented a wide variety of entertainment genres, and comedy—often in skits, often blended with singing, dancing, and novelty acts—was a big part of the draw. As the vaudeville circuits dried up after World War II, new opportunities bloomed. Nightclubs offered shorter, less diverse programs. And the acts were smaller: comic ensembles were winnowed down to small teams or, in many cases, solo performers. So widespread was this latter phenomenon, and so new, that Variety, the font of so much show-biz jargon over the century of its publication and influence, began to use a new term for it—“stand-up comedy”—in 1950.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

By the fifties, stand-up had taken on the form we recognize today: the loner at the mic telling jokes and stories, spewing one-liners, sometimes riffing off the audience either as a premeditated strategy or as a form or reaction or even in self-defense. As so many other aspects of the culture did, stand-up comedy changed from something standardized, impersonal, and traditional into something experimental, idiosyncratic, and revelatory.

In the 1950s, just as the groundbreaking practice of method acting demanded that actors look into themselves to mine truths, a new type of comedy based in political commentary, personal psychology, spontaneous improvisation, and an attitude of cynicism and even hostility toward the status quo emerged. New comedians, almost always working from material that they themselves had written, appeared seemingly in a giant wave, turning stand-up comedy from a form of amusement into a form of self-expression, consciousness raising, even social critique.

They were a distinctly diverse group, but they were lumped together by commentators and critics as the “sick comics”——as if their attempts to somehow personalize their material signaled mental derangement. And there was something else unique about this generation of comedians: it included Black performers such as Dick Gregory and Godfrey Cambridge, and it included (or would soon include) such women as Moms Mabley, Elaine May (with her partner Mike Nichols), and Phyllis Diller. As a generation, they would establish new standards of originality and idiosyncrasy in the field. It may have been a sign of “sickness” in some eyes that women were being allowed the same chances as men to be funny or fail in the effort. But as the early history of women stand-up comedians demonstrates, those who persevered and made places for themselves in the field were anything but frail or debilitated.

Today, the notion that women can be stand-up comedians is commonplace. But when many began their careers—and, in some cases, even when they retired or died—the very idea was a matter of puzzlement and consternation. Thanks to their fortitude, we are in a far richer place. And we’ve had more than a few real laughs in getting here.

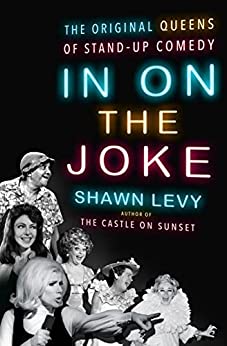

Adapted from In On the Joke: The Original Queens of Standup Comedy by Shawn Levy, available April 5 from Doubleday. Copyright © 2022 by Shawn Levy.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com