In a few minutes, electronic music will start pulsing, stuffed animals will be flung through the air, women will emerge spinning Technicolor hula hoops, and a mechanical bull will rev into action, bucking off one delighted rider after another. It’s the closing party of ETHDenver, a weeklong cryptocurrency conference dedicated to the blockchain Ethereum. Lines have stretched around the block for days. Now, on this Sunday night in February, the giddy energy is peaking.

But as the crowd pushes inside, a wiry man with elfin features is sprinting out of the venue, past astonished selfie takers and venture capitalists. Some call out, imploring him to stay; others even chase him down the street, on foot and on scooters. Yet the man outruns them all, disappearing into the privacy of his hotel lobby, alone.

Vitalik Buterin, the most influential person in crypto, didn’t come to Denver to party. He doesn’t drink or particularly enjoy crowds. Not that there isn’t plenty for the 28-year-old creator of Ethereum to celebrate. Nine years ago, Buterin dreamed up Ethereum as a way to leverage the blockchain technology underlying Bitcoin for all sorts of uses beyond currency. Since then, it has emerged as the bedrock layer of what advocates say will be a new, open-source, decentralized internet. Ether, the platform’s native currency, has become the second biggest cryptocurrency behind Bitcoin, powering a trillion-dollar ecosystem that rivals Visa in terms of the money it moves. Ethereum has brought thousands of unbanked people around the world into financial systems, allowed capital to flow unencumbered across borders, and provided the infrastructure for entrepreneurs to build all sorts of new products, from payment systems to prediction markets, digital swap meets to medical-research hubs.

But even as crypto has soared in value and volume, Buterin has watched the world he created evolve with a mixture of pride and dread. Ethereum has made a handful of white men unfathomably rich, pumped pollutants into the air, and emerged as a vehicle for tax evasion, money laundering, and mind-boggling scams. “Crypto itself has a lot of dystopian potential if implemented wrong,” the Russian-born Canadian explains the morning after the party in an 80-minute interview in his hotel room.

Buterin worries about the dangers to overeager investors, the soaring transaction fees, and the shameless displays of wealth that have come to dominate public perception of crypto. “The peril is you have these $3 million monkeys and it becomes a different kind of gambling,” he says, referring to the Bored Ape Yacht Club, an überpopular NFT collection of garish primate cartoons that has become a digital-age status symbol for millionaires including Jimmy Fallon and Paris Hilton, and which have traded for more than $1 million a pop. “There definitely are lots of people that are just buying yachts and Lambos.”

Read More: Politicians Show Their Increasing Interest In Crypto at ETHDenver 2022

Buterin hopes Ethereum will become the launchpad for all sorts of sociopolitical experimentation: fairer voting systems, urban planning, universal basic income, public-works projects. Above all, he wants the platform to be a counterweight to authoritarian governments and to upend Silicon Valley’s stranglehold over our digital lives. But he acknowledges that his vision for the transformative power of Ethereum is at risk of being overtaken by greed. And so he has reluctantly begun to take on a bigger public role in shaping its future. “If we don’t exercise our voice, the only things that get built are the things that are immediately profitable,” he says, reedy voice rising and falling as he fidgets his hands and sticks his toes between the cushions of a lumpy gray couch. “And those are often far from what’s actually the best for the world.”

The irony is that despite all of Buterin’s cachet, he may not have the ability to prevent Ethereum from veering off course. That’s because he designed it as a decentralized platform, responsive not only to his own vision but also to the will of its builders, investors, and ever sprawling community. Buterin is not the formal leader of Ethereum. And he fundamentally rejects the idea that anyone should hold unilateral power over its future.

Which has left Buterin reliant on the limited tools of soft power: writing blog posts, giving interviews, conducting research, speaking at conferences where many attendees just want to bask in the glow of their newfound riches. “I’ve been yelling a lot, and sometimes that yelling does feel like howling into the wind,” he says, his eyes darting across the room. Whether or not his approach works (and how much sway Buterin has over his own brainchild) may be the difference between a future in which Ethereum becomes the basis of a new era of digital life, and one in which it’s just another instrument of financial speculation—credit-default swaps with a utopian patina.

Three days after the music stops at ETHDenver, Buterin’s attention turns across the world, back to the region where he was born. In the war launched by Russian President Vladimir Putin, cryptocurrency almost immediately became a tool of Ukrainian resistance. More than $100 million in crypto was raised in the invasion’s first three weeks for the Ukrainian government and NGOs. Cryptocurrency has also provided a lifeline for some fleeing Ukrainians whose banks are inaccessible. At the same time, regulators worry that it will be used by Russian oligarchs to evade sanctions.

Buterin has sprung into action too, matching hundreds of thousands of dollars in grants toward relief efforts and publicly lambasting Putin’s decision to invade. “One silver lining of the situation in the last three weeks is that it has reminded a lot of people in the crypto space that ultimately the goal of crypto is not to play games with million-dollar pictures of monkeys, it’s to do things that accomplish meaningful effects in the real world,” Buterin wrote in an email to TIME on March 14.

His outspoken advocacy marks a change for a leader who has been slow to find his political voice. “One of the decisions I made in 2022 is to try to be more risk-taking and less neutral,” Buterin says. “I would rather Ethereum offend some people than turn into something that stands for nothing.”

The war is personal to Buterin, who has both Russian and Ukrainian ancestry. He was born outside Moscow in 1994 to two computer scientists, Dmitry Buterin and Natalia Ameline, a few years after the fall of the Soviet Union. Monetary and social systems had collapsed; his mother’s parents lost their life savings amid rising inflation. “Growing up in the USSR, I didn’t realize most of the stuff I’d been told in school that was good, like communism, was all propaganda,” explains Dmitry. “So I wanted Vitalik to question conventions and beliefs, and he grew up very independent as a thinker.”

The family initially lived in a university dorm room with a shared bathroom. There were no disposable diapers available, so his parents washed his by hand. Vitalik grew up with a turbulent, teeming mind. Dmitry says Vitalik learned how to read before he could sleep through the night, and was slow to form sentences compared with his peers. “Because his mind was going so fast,” Dmitry recalls, “it was actually hard for him to express himself verbally for some time.”

Instead, Vitalik gravitated to the clarity of numbers. At 4, he inherited his parents’ old IBM computer and started playing around with Excel spreadsheets. At 7, he could recite more than a hundred digits of pi, and would shout out math equations to pass the time. By 12, he was coding inside Microsoft Office Suite. The precocious child’s isolation from his peers had been exacerbated by a move to Toronto in 2000, the same year Putin was first elected. His father characterizes Vitalik’s Canadian upbringing as “lucky and naive.” Vitalik himself uses the words “lonely and disconnected.”

In 2011, Dmitry introduced Vitalik to Bitcoin, which had been created in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis. After seeing the collapse of financial systems in both Russia and the U.S., Dmitry was intrigued by the idea of an alternative global money source that was uncontrolled by authorities. Vitalik soon began writing articles exploring the new technology for the magazine Bitcoin Weekly, for which he earned 5 bitcoins a pop (back then, some $4; today, it would be worth about $200,000).

Even as a teenager, Vitalik Buterin proved to be a pithy writer, able to articulate complex ideas about cryptocurrency and its underlying technology in clear prose. At 18, he co-founded Bitcoin Magazine and became its lead writer, earning a following both in Toronto and abroad. “A lot of people think of him as a typical techie engineer,” says Nathan Schneider, a media-studies professor at the University of Colorado, Boulder, who first interviewed Buterin in 2014. “But a core of his practice even more so is observation and writing—and that helped him see a cohesive vision that others weren’t seeing yet.”

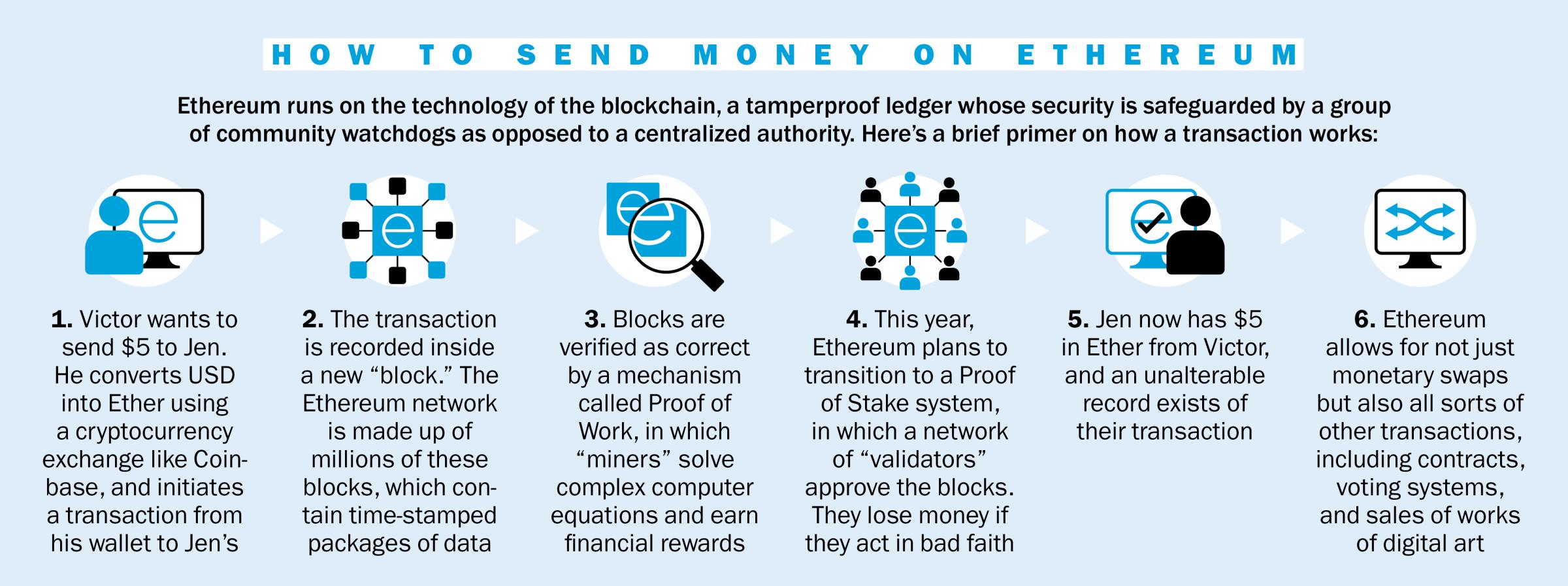

As Buterin learned more about the blockchain technology on which Bitcoin was built, he began to believe using it purely for currency was a waste. The blockchain, he thought, could serve as an efficient method for securing all sorts of assets: web applications, organizations, financial derivatives, nonpredatory loan programs, even wills. Each of these could be operated by “smart contracts,” code that could be programmed to carry out transactions without the need for intermediaries. A decentralized version of the rideshare industry, for example, could be built to send money directly from passengers to drivers, without Uber swiping a cut of the proceeds.

Read the rest of Buterin’s interview in TIME’s newsletter Into the Metaverse. Subscribe for a weekly guide to the future of the Internet. You can find past issues of the newsletter here.

In 2013, Buterin dropped out of college and wrote a 36-page white paper laying out his vision for Ethereum: a new open-source blockchain on which programmers could build any sort of application they wished. (Buterin swiped the name from a Wikipedia list of elements from science fiction.) He sent it to friends in the Bitcoin community, who passed it around. Soon a handful of programmers and businessmen around the world sought out Buterin in hopes of helping him bring it to life. Within months, a group of eight men who would become known as Ethereum’s founders were sharing a three-story Airbnb in Switzerland, writing code and wooing investors.

While some of the other founders mixed work and play—watching Game of Thrones, persuading friends to bring over beer in exchange for Ether IOUs—Buterin mostly kept to himself, coding away on his laptop, according to Laura Shin’s recent book about the history of Ethereum, The Cryptopians. Over time, it became apparent that the group had very different plans for the nascent technology. Buterin wanted a decentralized open platform on which anyone could build anything. Others wanted to use the technology to create a business. One idea was to build the crypto equivalent to Google, in which Ethereum would use customer data to sell targeted ads. The men also squabbled over power and titles. One co-founder, Charles Hoskinson, appointed himself CEO—a designation that was of no interest to Buterin, who joked his title would be C-3PO, after the droid from Star Wars.

The ensuing conflicts left Buterin with culture shock. In the space of a few months, he had gone from a cloistered life of writing code and technical articles to a that of a decisionmaker grappling with bloated egos and power struggles. His vision for Ethereum hung in the balance. “The biggest divide was definitely that a lot of these people cared about making money. For me, that was totally not my goal,” says Buterin, whose net worth is at least $800 million, according to public records on the blockchain whose accuracy was confirmed by a spokesperson. “There were even times at the beginning where I was negotiating down the percentages of the Ether distribution that both myself and the other top-level founders would get, in order to be more egalitarian. That did make them upset.”

Buterin says the other founders tried to take advantage of his naiveté to push through their own ideas about how Ethereum should run. “People used my fear of regulators against me,” he recalls, “saying that we should have a for-profit entity because it’s so much simpler legally than making a nonprofit.” As tensions rose, the group implored Buterin to make a decision. In June 2014, he asked Hoskinson and Amir Chetrit, two co-founders who were pushing Ethereum to become a business, to leave the group. He then set in motion the creation of the Ethereum Foundation (EF), a nonprofit established to safeguard Ethereum’s infrastructure and fund research and development projects.

One by one, all the other founders peeled off over the next few years to pursue their own projects, either in tandem with Ethereum or as direct competitors. Some of them remain critical of Buterin’s approach. “In the dichotomy between centralization and anarchy, Ethereum seems to be going toward anarchy,” says Hoskinson, who now leads his own blockchain, Cardano. “We think there’s a middle ground to create some sort of blockchain-based governance system.”

With the founders splintered, Buterin emerged as Ethereum’s philosophical leader. He had a seat on the EF board and the clout to shape industry trends and move markets with his public pronouncements. He even became known as “V God” in China. But he didn’t exactly step into the power vacuum. “He’s not good at bossing people around,” says Aya Miyaguchi, the executive director of the EF. “From a social-navigation perspective, he was immature. He’s probably still conflict-averse,” says Danny Ryan, a lead researcher at the EF. Buterin calls his struggle to inhabit the role of an organizational leader “my curse for the first few years at Ethereum.”

It’s not hard to see why. Buterin still does not present stereotypical leadership qualities when you meet him. He sniffles and stutters through his sentences, walks stiffly, and struggles to hold eye contact. He puts almost no effort into his clothing, mostly wearing Uniqlo tees or garments gifted to him by friends. His disheveled appearance has made him an easy target on social media: he recently shared insults from online hecklers who said he looked like a “Bond villain” or an “alien crackhead.”

Yet almost everyone who has a full conversation with Buterin comes away starry-eyed. Buterin is wryly funny and almost wholly devoid of pretension or ego. He’s an unabashed geek whose eyes spark when he alights upon one of his favorite concepts, whether it be quadratic voting or the governance system futarchy. Just as Ethereum is designed to be an everything machine, Buterin is an everything thinker, fluent in disciplines ranging from sociological theory to advanced calculus to land-tax history. (He’s currently using Duolingo to learn his fifth and sixth languages.) He doesn’t talk down to people, and he eschews a security detail. “An emotional part of me says that once you start going down that way, professionalizing is just another word for losing your soul,” he says.

Alexis Ohanian, the co-founder of Reddit and a major crypto investor, says being around Buterin gives him “a similar vibe to when I first got to know Sir Tim Berners-Lee,” the inventor of the World Wide Web. “He’s very thoughtful and unassuming,” Ohanian says, “and he’s giving the world some of the most powerful Legos it’s ever seen.”

For years, Buterin has been grappling with how much power to exercise in Ethereum’s decentralized ecosystem. The first major test came in 2016, when a newly created Ethereum-based fundraising body called the DAO was hacked for $60 million, which amounted at the time to more than 4% of all Ether in circulation. The hack tested the crypto community’s values: if they truly believed no central authority should override the code governing smart contracts, then thousands of investors would simply have to eat the loss—which could, in turn, encourage more hackers. On the other hand, if Buterin chose to reverse the hack using a maneuver called a hard fork, he would be wielding the same kind of central authority as the financial systems he sought to replace.

Buterin took a middle ground. He consulted with other Ethereum leaders, wrote blog posts advocating for the hard fork, and watched as the community voted overwhelmingly in favor of that option via forums and petitions. When Ethereum developers created the fork, users and miners had the option to stick with the hacked version of the blockchain. But they overwhelmingly chose the forked version, and Ethereum quickly recovered in value.

To Buterin, the DAO hack epitomized the promise of a decentralized approach to governance. “Leadership has to rely much more on soft power and less on hard power, so leaders have to actually take into account the feelings of the community and treat them with respect,” he says. “Leadership positions aren’t fixed, so if leaders stop performing, the world forgets about them. And the converse is that it’s very easy for new leaders to rise up.”

Over the past few years, countless leaders have risen up in Ethereum, building all kinds of products, tokens, and subcultures. There was the ICO boom of 2017, in which venture capitalists raised billions of dollars for blockchain projects. There was DeFi summer in 2020, in which new trading mechanisms and derivative structures sent money whizzing around the world at hyperspeed. And there was last year’s explosion of NFTs: tradeable digital goods, like profile pictures, art collections, and sports cards, that skyrocketed in value.

Skeptics have derided the utility of NFTs, in which billion-dollar economies have been built upon the perceived digital ownership of simple images that can easily be copied and pasted. But they have rapidly become one of the most utilized components of the Ethereum ecosystem. In January, the NFT trading platform OpenSea hit a record $5 billion in monthly sales.

Buterin didn’t predict the rise of NFTs, and has watched the phenomenon with a mixture of interest and anxiety. On one hand, they have helped to turbocharge the price of Ether, which has increased more than tenfold in value over the past two years. (Disclosure: I own less than $1,300 worth of Ether, which I purchased in 2021.) But their volume has overwhelmed the network, leading to a steep rise in congestion fees, in which, for instance, bidders trying to secure a rare NFT pay hundreds of dollars extra to make sure their transactions are expedited.

Read More: NFT Art Collectors Are Playing a Risky Game—And Winning

The fees have undermined some of Buterin’s favorite projects on the blockchain. Take Proof of Humanity, which awards a universal basic income—currently about $40 per month—to anyone who signs up. Depending on the week, the network’s congestion fees can make pulling money out of your wallet to pay for basic needs prohibitively expensive. “With fees being the way they are today,” Buterin says, “it really gets to the point where the financial derivatives and the gambley stuff start pricing out some of the cool stuff.”

Inequities have crept into crypto in other ways, including a stark lack of gender and racial diversity. “It hasn’t been among the things I’ve put a lot of intellectual effort into,” Buterin admits of gender parity. “The ecosystem does need to improve there.” He’s scornful of the dominance of coin voting, a voting process for DAOs that Buterin feels is just a new version of plutocracy, one in which wealthy venture capitalists can make self-interested decisions with little resistance. “It’s become a de facto standard, which is a dystopia I’ve been seeing unfolding over the last few years,” he says.

These problems have sparked a backlash both inside and outside the blockchain community. As crypto rockets toward the mainstream, its esoteric jargon, idiosyncratic culture, and financial excesses have been met with widespread disdain. Meanwhile, frustrated users are decamping to newer blockchains like Solana and BNB Chain, driven by the prospect of lower transaction fees, alternative building tools, or different philosophical values.

Buterin understands why people are moving away from Ethereum. Unlike virtually any other leader in a trillion-dollar industry, he says he’s fine with it—especially given that Ethereum’s current problems stem from the fact that it has too many users. (Losing immense riches doesn’t faze him much, either: last year, he dumped $6 billion worth of Shiba Inu tokens that were gifted to him, explaining that he wanted to give some to charity, help maintain the meme coin’s value, and surrender his role as a “locus of power.”)

In the meantime, he and the EF—which holds almost a billion dollars worth of Ether in reserve, a representative confirmed—are taking several approaches to improve the ecosystem. Last year, they handed out $27 million to Ethereum-based projects, up from $7.7 million in 2019, to recipients including smart-contract developers and an educational conference in Lagos.

The EF research team is also working on two crucial technical updates. The first is known as the “merge,” which converts Ethereum from Proof of Work, a form of blockchain verification, to Proof of Stake, which the EF says will reduce Ethereum’s energy usage by more than 99% and make the network more secure. Buterin has been stumping for Proof of Stake since Ethereum’s founding, but repeated delays have turned implementation into a Waiting for Godot–style drama. At ETHDenver, the EF researcher Danny Ryan declared that the merge would happen within the next six months, unless “something insanely catastrophic” happens. The same day, Buterin encouraged companies worried about the environmental impact to delay using Ethereum until the merge is completed—even if it “gets delayed until 2025.”

After the merge, Buterin hopes to scale the technology. The most crucial tool in doing so is sharding, which Buterin says will lead to faster response times and eventually lower fees to around a nickel. But as the EF works on sharding, users

are already flocking to centralized blockchains and platforms that run faster and work better.

In January, Moxie Marlinspike, co-founder of the messaging app Signal, wrote a widely read critique noting that despite its collectivist mantras, so-called web3 was already coalescing around centralized platforms. As he often does when faced with legitimate criticism, Buterin responded with a thoughtful, detailed post on Reddit. “The properly authenticated decentralized blockchain world is coming, and is much closer to being here than many people think,” he wrote. “I see no technical reason why the future needs to look like the status quo today.”

Buterin is aware that crypto’s utopian promises sound stale to many, and calls the race to implement sharding in the face of competition a “ticking time bomb.” “If we don’t have sharding fast enough, then people might just start migrating to more centralized solutions,” he says. “And if after all that stuff happens and it still centralizes, then yes, there’s a much stronger argument that there’s a big problem.”

As the technical kinks get worked out, Buterin has turned his attention toward larger sociopolitical issues he thinks the blockchain might solve. On his blog and on Twitter, you’ll find treatises on housing; on voting systems; on the best way to distribute public goods; on city building and longevity research. While Buterin spent much of the pandemic living in Singapore, he increasingly lives as a digital nomad, writing dispatches from the road.

Those who know Buterin well have noticed a philosophical shift over the years. “He’s gone on a journey from being more sympathetic to anarcho-capitalist thinking to Georgist-type thinking,” says Glen Weyl, an economist who is one of his close collaborators, referring to a theory that holds the value of the commons should belong equally to all members of society. One of Buterin’s recent posts calls for the creation of a new type of NFT, based not on monetary value but on participation and identity. For instance, the allocation of votes in an organization might be determined by the commitment an individual has shown to the group, as opposed to the number of tokens they own. “NFTs can represent much more of who you are and not just what you can afford,” he writes.

Read More: How Crypto Investors Are Handling Plunging Prices

While Buterin’s blog is one of his main tools of public persuasion, his posts aren’t meant to be decrees, but rather intellectual explorations that invite debate. Buterin often dissects the flaws of obscure ideas he once wrote effusively about, like Harberger taxes. His blog is a model for how a leader can work through complex ideas with transparency and rigor, exposing the messy process of intellectual growth for all to see, and perhaps learn from.

Some of Buterin’s more radical ideas can provoke alarm. In January, he caused a minor outrage on Twitter by advocating for synthetic wombs, which he argued could reduce the pay gap between men and women. He predicts there’s a decent chance someone born today will live to be 3,000, and takes the anti-diabetes medication Metformin in the hope of slowing his body’s aging, despite mixed studies on the drug’s efficacy.

Subscribe to TIME’s newsletter Into the Metaverse for a weekly guide to the future of the Internet. You can find past issues of the newsletter here.

As governmental bodies prepare to wade into crypto—in March, President Biden signed an Executive Order seeking a federal plan for regulating digital assets—Buterin has increasingly been sought out by politicians. At ETHDenver, he held a private conversation with Colorado Governor Jared Polis, a Democrat who supports cryptocurrencies. Buterin is anxious about crypto’s political valence in the U.S., where Republicans have generally been more eager to embrace it. “There’s definitely signs that are making it seem like crypto is on the verge of becoming a right-leaning thing,” Buterin says. “If it does happen, we’ll sacrifice a lot of the potential it has to offer.”

To Buterin, the worst-case scenario for the future of crypto is that blockchain technology ends up concentrated in the hands of dictatorial governments. He is unhappy with El Salvador’s rollout of Bitcoin as legal tender, which has been riddled with identity theft and volatility. The prospect of governments using the technology to crack down on dissent is one reason Buterin is adamant about crypto remaining decentralized. He sees the technology as the most powerful equalizer to surveillance technology deployed by governments (like China’s) and powerful companies (like Meta) alike.

If Mark Zuckerberg shouldn’t have the power to make epoch-changing decisions or control users’ data for profit, Buterin believes, then neither should he—even if that limits his ability to shape the future of his creation, sends some people to other blockchains, or allows others to use his platform in unsavory ways. “I would love to have an ecosystem that has lots of good crazy and bad crazy,” Buterin says. “Bad crazy is when there’s just huge amounts of money being drained and all it’s doing is subsidizing the hacker industry. Good crazy is when there’s tech work and research and development and public goods coming out of the other end. So there’s this battle. And we have to be intentional, and make sure more of the right things happen.”

—With reporting by Nik Popli and Mariah Espada/Washington

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com