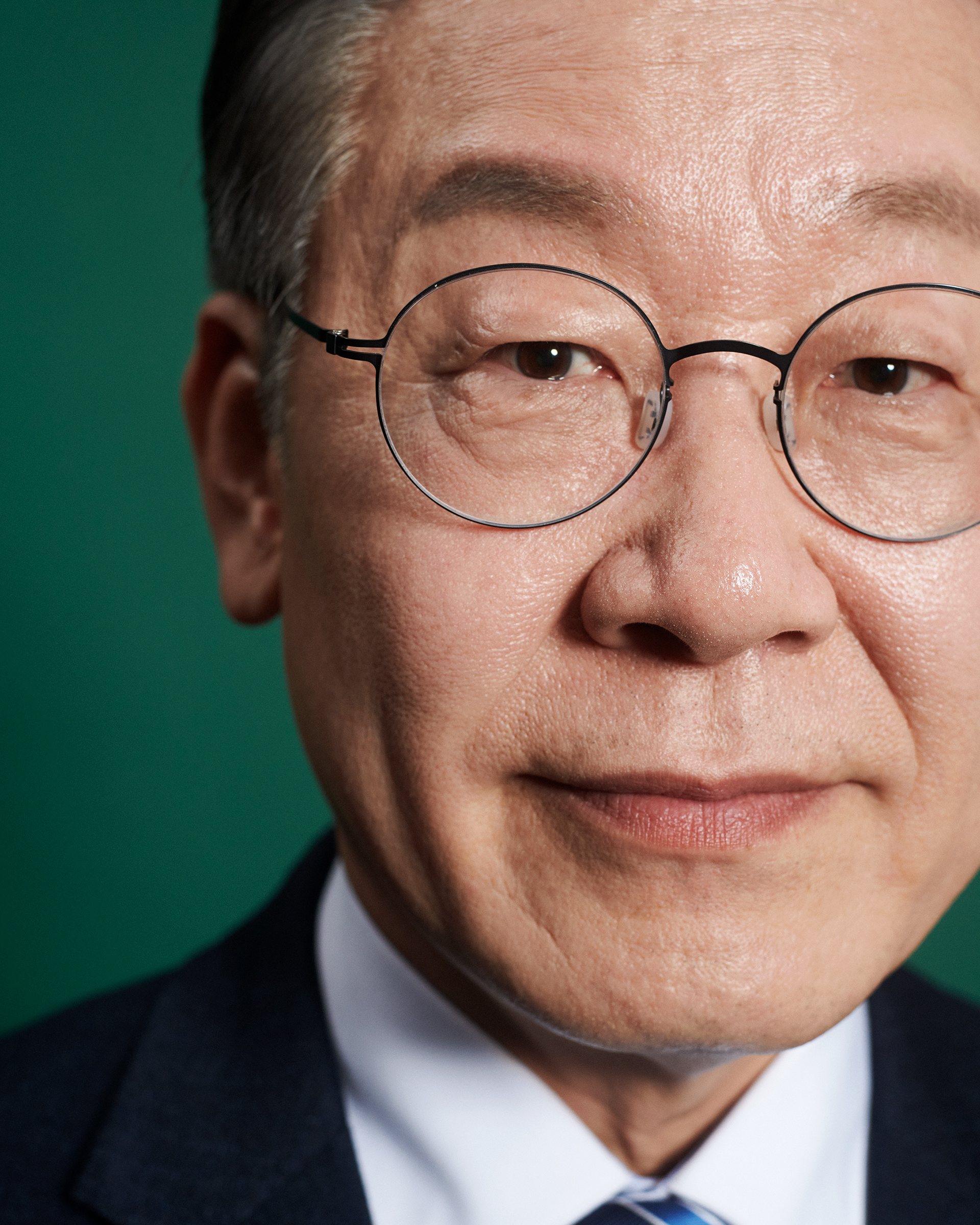

It’s an old cliche that presidential hopefuls win votes by kissing babies. But it’s a brave parent who offers their infant to Lee Jae-myung, whose signature moves on the campaign trail are taekwondo kicks and punches, shattering boards labeled “COVID-19 crisis” and “pain of small business owners” in front of whooping supporters. “My staff asked me to do it,” Lee laughs, throwing a stiff jab at his laptop lens during our Zoom interview. “All Korean men know the basics of taekwondo.”

If Lee is successful in South Korea’s March 9 election, then he’ll have to smash through more than just boards. Voters are demanding that whoever ends up in the presidential Blue House dismantle the rampant inequality that plagues South Korean society, a condition underscored by a series of scandals that emerged during the tenure of incumbent President Moon Jae-in, such as local officials using insider knowledge to speculate on property while housing prices soar. (Lee is representing the same Democratic Party as Moon, who is constitutionally ineligible to stand for a second term.)

“Lee has proven he is the one who can reform [Korea],” says Choo Yeon-chang, 65, who came to watch one of Lee’s rallies in the southern city of Daegu. “He can boost the morale of the entire country and bring change.”

Lee, 57, served as mayor of the city of Seongnam for seven years and, until the campaign, was governor of Gyeonggi Province, which surrounds Seoul and is South Korea’s most populous. He shot to national prominence through his uncompromising handling of the COVID-19 pandemic—even tactfully negotiating with the leader of a shadowy religious sect to allow testing within his commune—and advocating for universal basic income (UBI), where 1 million won ($840) would eventually be given to every citizen. It would make South Korea the only major economy to adopt a UBI, at a time of soaring inequality. (Finland ran a UBI experiment from 2017 to 2018, and Democratic U.S. presidential hopeful Andrew Yang has previously advocated a similar scheme). Lee is also campaigning on progressive policies like ensuring that at least 30% of top officials are women. (In April 2020, a record 57 women were elected to the 300-seat parliament; though just 19%, the proportion was the highest ever since democratization in 1987.) It’s an urge that comes from “actually going through and experiencing [injustice] myself,” he says. “That desperate sense has definitely been a driving force for me in pursuing my political career.”

Lee’s opponent in the race is fellow lawyer Yoon Suk-yeol, standing for the main opposition conservative People Power Party, who as prosecutor general made his name pursuing high-profile corruption cases against jailed former President Park Geun-hye, as well as Moon’s administration. Although Yoon has no governing experience, he’s seen as a populist whose following is owed to a graft-busting image. (Yoon declined a request for an interview with TIME.) The last permitted polling before the ballot, published March 3, had both candidates neck and neck.

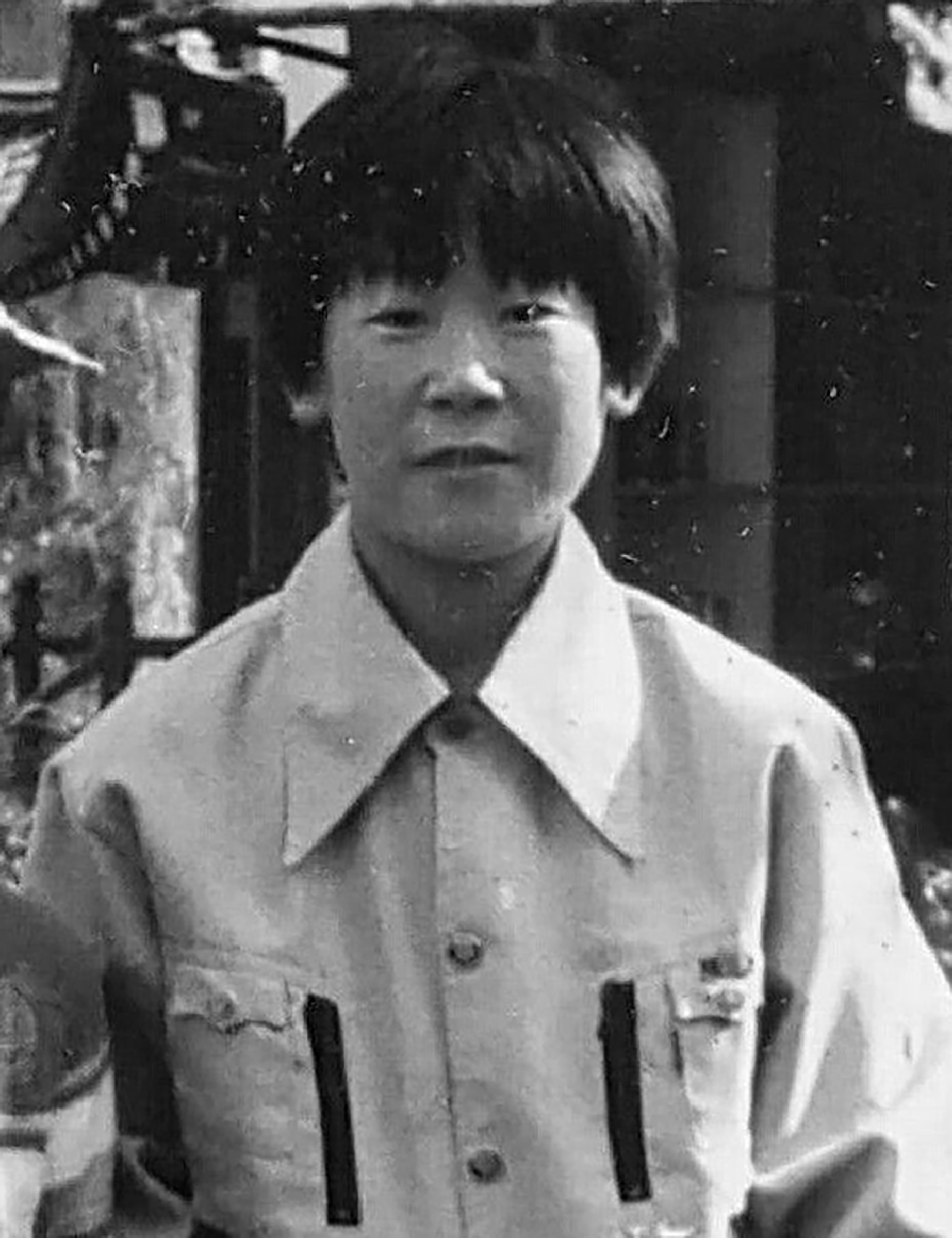

From “the most backward place of 20th century Korea”

Lee’s appeal to South Korea’s downtrodden are not just words. Born the fifth of seven children in an impoverished farming family, Lee would walk a 10 mile round trip to elementary school daily before returning home to plow fields. Too poor to afford even paper or crayons, Lee once had to clean the school toilets while his classmates attended an art contest. The school’s small library was his sanctuary, where he devoured adventure books such as Jules Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea to escape the harsh reality of going hungry day after day.

Lee left school in his early teens, lying about his age to work in factories, where he was frequently hostage to unscrupulous bosses’ withholding wages. One day, he got his wrist crushed in a pressing machine, an injury so serious that it meant he was officially designated as disabled and excused from national service. That torment, combined with his father’s gambling addiction, even led him to attempt suicide.

The pain of those formative years opened the young Lee’s eyes to social injustice that still plagues Korean society. Despite South Korea’s riches, it is also where even top college graduates struggle to earn enough to get a foot on the housing ladder, and where pensioners must recycle cardboard to make ends meet. Disposable income for the top 20% of earners is 5.59 times as high as that for the lowest 20%, according to Statistics Korea.

“Before, I actually thought it was all my fault, it was my mistake, and my responsibility,” Lee says. “Later on, as I became a college student, I realized that it was actually a structural social issue. And I made a commitment that, if possible, I would not leave any people to live the same life as I did.”

Despite no formal secondary education, Lee was accepted to law school on his first attempt, later forging a career in politics. A cornerstone of his stint as mayor of Seongnam was paying “youth dividends” of 250,000 won ($200) per quarter to 24-year-old residents, which became so successful that he expanded the program across Gyeonggi Province when he became governor in 2018. If he wins, Lee’s UBI would be an extension of coronavirus-linked assistance that he rolled out in Gyeonggi Province, where each resident received 100,000 won ($80) last year but had to spend it within three months in order to boost local business.

“Lee originated from the most backward place of 20th century Korea,” says Bang Hyeon-seok, a professor at ChungAng University who authored an authoritative biography of Lee, “and is now standing on the front line of 21st century Korea.”

North Korea, the noisy neighbor

While domestic issues are dominating the campaign, tensions across the demilitarized zone (DMZ) are once again rearing their head after North Korea hit a record month of missile testing in January, with 10 launches. Despite the unprecedented engagement of Moon and former U.S. President Donald Trump, Kim Jong Un still has around 60 nuclear bombs, according to best estimates, as well as intercontinental ballistic missiles capable of devastating any U.S. city. North Korea is also developing the capability to launch nuclear-tipped missiles from submarines. In January, Yoon alarmed many by advocating a pre-emptive military strike against the Kim regime if provocations escalate. (Yoon doubled down when challenged on the wisdom of a pre-emptive strike, saying it would be to “protect peace.”) For Lee, that is dangerous talk. “A lot of wars broke out not because of national interest, but because of such heated, emotional exchanges,” he says. “It’s important that we should not have any kind of unnecessary stimulation … that could escalate military tension.”

The specter of conflict has rarely felt so close. Russian President Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine has already killed hundreds and displaced 1 million people, according to the U.N. Thousands of miles away, the invasion has brought back painful memories of when the Korean peninsula was occupied by the Japanese during World War II and the subsequent invasion by Soviet-backed forces in 1950, remaining today riven by Cold War animosities.

It’s lost on few here that North Korea’s only ally is China, which has refused to condemn Russia’s invasion, with Chinese President Xi Jinping’s meeting Putin in Beijing just days before tanks rolled into Ukraine to hail a strategic partnership “without limits.” That Russia, a historic backer of North Korea, just invaded a sovereign nation of 44 million with the tacit support of Beijing is naturally a cause for alarm. Under Moon, South Korea has indicated willingness to engage more in the U.S.-led Indo-Pacific Strategy and so-called Quad Plus security apparatus, groupings of Asian-Pacific democracies united to constrain China. He even emphasized the importance of “peace and stability in the Taiwan Strait,” provoking a rebuke from Beijing. “For South Korea, imagining this bloc of China, Russia, and North Korea hardening is an uncomfortable thought,” says Professor John Delury, an East Asia expert at Yonsei University in Seoul.

Read More: Queer South Koreans Hope for an Anti-Discrimination Law to End Decades of Discrimination

In many ways, Lee’s rags-to-riches success story finds parallels in the story of South Korea itself. Despite being decimated following World War II and the 1950–’53 Korean War, the nation today with its population of 50 million boasts the world’s 10th largest economy, whose firms—like Samsung Electronics and Hyundai Motors—are global behemoths. More recently, Korean culture—including food, TV and K-pop music—have drawn huge followings around the world. After a string of Korean smash hits, streaming giant Netflix has said it will at least match the $460 million it spent in 2021 in the country this year. Asked whether the “boom” of Korean culture was important, Lee offers a correction: “I would like to wish and hope that it’s only in the beginning, initial stages.” While South Korea’s traditional influence is constrained by limits in terms of territory and population, if you look at the “soft power” side, Lee says, “the possibilities are endless.”

Nonetheless, the invasion of Ukraine has South Korea once again looking over its shoulder. Lee expresses “outrage” at Russia’s aggression and insists that the rules-based world order must be strengthened in the face of such violations. “It’s very important that the international community realizes and reaffirms its commitment once again that any type of invasion that threatens the territorial integrity and sovereignty of a nation should not be overlooked,” he says.

To stave off war with the North, Lee wants to continue with the “sunshine policy” resurrected by Moon, who over the course of 18 months navigated an astonishing process of engagement. Kim held three summits with Moon, five with Xi, one with Putin, and three with Trump, who said of the dictator following a summit in Singapore: “We fell in love.” Yet all that effort has achieved very little concrete reconciliation. In June 2020, North Korea blew up a joint liaison office near the border town of Kaesong.

For Lee, the major factor in the stalled progress is a lack of trust. “Nothing gets resolved through force,” he says. “North Korea is also voicing frustration that some of the agreements [from Moon and Trump] were not upheld from our side.” Asked what his message is for Kim, he says that escalations like missile tests “will only further isolate them from the international society and … cost them the opportunity to cooperate with other countries. It’s not beneficial for the advancement or development of North Korea itself.”

Still, engaging the North remains a deeply polarizing issue among South Korean voters. “Moon is a dictator and he is a friend of Kim Jong Un,” one elderly conservative Daegu resident tells TIME near Lee’s campaign rally. “Moon and his party are trying to give all the money we have to North Korea. Lee will be no different from Moon.”

Managing Expectations of a Breakthrough

The unfortunate reality is that it will be extremely difficult to win over the U.S. and international community on inter-Korean economic cooperation without real, verifiable progress on denuclearization. And whether any deal is now possible is a huge question. North Korea has completely sequestered itself since the pandemic, even turning away food aid. Kim demands the complete suspension of South Korea-U.S. joint military exercises as a condition for dialogues with both countries, which is a nonstarter for Washington. “No matter which candidate becomes elected in [South Korea], it appears to be difficult to induce a resumption of stalled inter-Korean and Washington-Pyongyang dialogues” says Cheong Seong-chang, a senior fellow at Seoul’s influential Sejong Institute think tank.

And if the fate of Ukraine has lessons for South Korea, it is strikingly relevant for North Korea too. Ukraine was the world’s third largest nuclear weapons state—its scientists actually helped Pyongyang develop its missiles—when the Soviet Union broke up. From Kim’s perspective, Ukraine’s fatal mistake was swapping out the opportunity to have a nuclear deterrent for security guarantees from Russia and the West. “The chance of North Korea believing in U.S.-offered security assurance in return for nuclear disarmament—lock, stock and barrel—is now close to zero,” Cheong says.

And with the world distracted by carnage in Eastern Europe, Cheong believes Kim will take the opportunity to further hone his weapons. Not least since it’s now nigh impossible for the U.S. to seek Russia’s consent for new U.N. Security Council sanctions against Pyongyang.

And so Lee believes that, if elected, he will have to work closer with Beijing to keep his country safe. “It is necessary for us to grow and expand a cooperative relationship with China that is mutually beneficial,” he says. “While we firmly voice our position when necessary.”

While advocating dialogue where possible, Lee also proposes shaking up the military establishment. South Korea hosts some 28,500 U.S. troops and Lee wants to continue Moon’s work of transferring Wartime Operational Control, or OPCON, of combined forces from the U.S. to the Korean military. He also wants South Korea to build nuclear-powered submarines,which can operate longer and farther from home than traditional submarines. This, he says, will allow South Korea to play a more prominent role in regional security. He is also eager to promote a “two-track strategy” to restore relations with Japan, which reached a nadir during the Moon administration because of South Korea’s pressing the Japanese on human-rights abuses during World War II.

Of course, putting this plan into action relies on first winning over South Korean voters. It’s been a pretty grubby campaign so far—even by the standards of South Korea, where sleaze and corruption allegations are commonplace. Lee had to apologize after his son was caught gambling illegally, and has faced allegations that he illegally hired a provincial government employee to serve as his wife’s personal assistant, who then misappropriated state funds via his corporate credit card. (Lee has vowed to cooperate with any investigation.) Meanwhile, three people associated with a corruption probe into scandals surrounding Lee have turned up dead. (Lee’s campaign team were quick to dismiss any connection to their candidate as “fake news.”)

Yoon, in turn, had to apologize for inaccuracies on his wife’s resume many years ago when she applied for teaching jobs and denied allegations she was guilty of stock manipulation. He has also denied accusations of an occult hand in his campaign, including links to a shaman and an anal acupuncturist. It’s hardly inspiring stuff. On March 3, a fringe conservative candidate, software mogul Ahn Cheol-soo, dropped out of the race and threw his backing behind Yoon.

Lee’s hopes appear to rest on the liberal voters’ consolidating behind him in response, on ordinary people’s seeing through the morass to focus on the issues that truly matter, and on his promise that he has the vision and track record to push real change. “There are many ways that you can learn about the world—it could be through books, it could be through anecdotes of other people,” he says, “but I think actually living it yourself, experiencing it, is a different thing.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Charlie Campbell at charlie.campbell@time.com