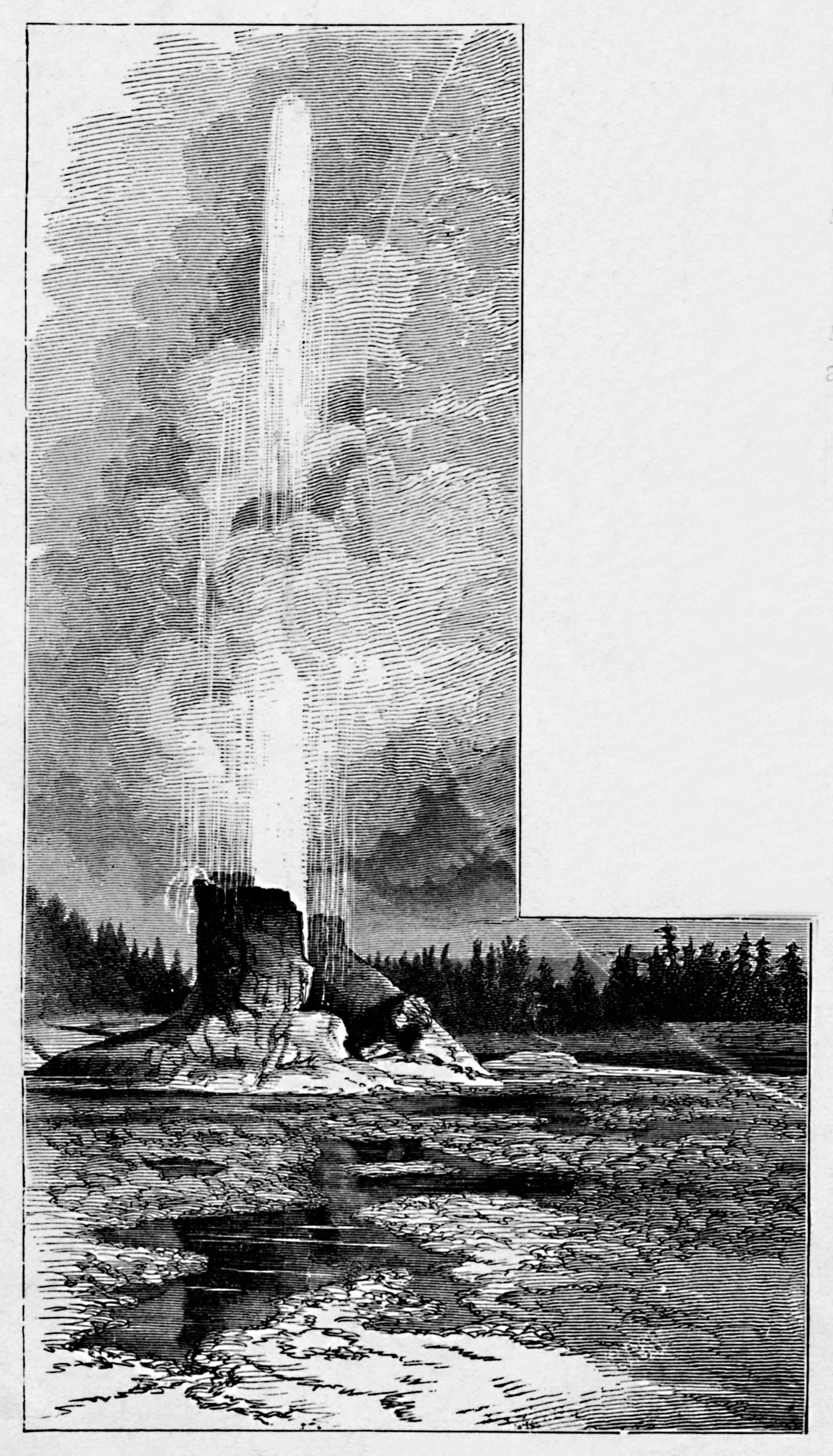

In the fall of 1871, Americans became aware of Yellowstone’s many natural wonders after geologist Ferdinand Hayden returned from a federally funded expedition to assess the region’s “geological, mineralogical, zoological, botanical, and agricultural resources.” Hayden sent reports and specimens to the Smithsonian Institution and the Department of the Interior, and described his discoveries in an article for the new middle-class magazine Scribner’s Monthly. In December, prompted by a Northern Pacific Railroad public relations manager looking to boost tourist traffic to the region, Hayden began to lobby Congressmen to pass an act to preserve Yellowstone as a national park.

The idea of preserving land for the people was not a new one in American culture. Europeans had come to North America with the tradition; in the mid-nineteenth century, a city park movement had taken hold in many urban areas. In the 1840s, the artist George Catlin, who had traveled up the Missouri River painting landscapes and portraits of Plains Indian and Lakota chiefs, suggested maintaining the entire continent west of that waterway as a pleasure park.

Read more: The Story Behind Those Gorgeous National Parks Posters From the 1930s

In 1864, Congress had passed the Yosemite Grant Act, which gave the massive granite domes and waterfalls of Yosemite and the awe-inspiring tall trees of the Mariposa Grove to the state of California. It was the first time in the history of the nation that Congress had acted explicitly to protect lands for recreation and aesthetic enjoyment—and to prevent their sale and development.

The Yellowstone legislation would be a slightly different kind of land-taking. Instead of giving public lands to a state, the federal government would take lands from a territory and give it to the Department of the Interior to manage. This was another unprecedented form of federal power exerted on the landscapes and tribal homelands of the West.

It was an immense tract of land: more than 1,760 square miles—larger than the state of Rhode Island. Preserving it, some believed, was an act unique in the world, worthy of a great republic. “That great National Park is such an idea,” one of Hayden’s fellow geologists wrote to him, “as could originate only in America.”

As Hayden met with Congressmen to lobby for Yellowstone National Park, he was joined by a number of interested parties. Jay Cooke, an investment banker who was selling bonds for the Northern Pacific Railroad, sent his brother Henry, who knew everyone worth knowing in Washington. He was a particular friend of Ulysses S. Grant, and he visited the president and several congressmen, talking up Yellowstone’s preservation and what it could mean for prospective white settlers of the Great Northwest. There was also the “Montana Group,” made up of civic leaders who had business interests in that territory.

During the next few weeks, Hayden and the Montana Group met with as many members of the House and Senate as they could. Yellowstone was a wonder of the world, they argued. Its lands would be a park worthy of the nation’s greatness; they must not fall prey to speculators and schemers. Hayden’s expedition that summer had proven that Yellowstone was useless for agricultural, mining, or manufacturing purposes. Therefore, its highest and best use would be as a place of resort for scientists and tourists. And its preservation would bring a rush of settlers—and business capital—to Montana Territory.

Read more: The Story We’ve Been Told About America’s National Parks Is Incomplete

Lobbying was just one of Hayden’s strategies. He also created an exhibit in the Capitol Rotunda, choosing fossils, minerals, photographs, and illustrations to display below a painting of the signing of the Declaration of Independence. It was a museum in miniature, a collection that linked the exploration of Yellowstone with America’s founding moments. The exhibit argued that America was, in fact, nature’s nation.

As a result of Hayden’s and the Montana Group’s efforts, the bill to preserve Yellowstone was introduced in December 1871 and came up for debate in January 1872.

But as newspapers across the nation began reporting on this new measure, it became clear that there was some resistance to the idea. Putting Yellowstone under federal control gave the Department of the Interior too much power, according to some. With that kind of authorization, what was to stop the secretary of the interior from leasing lands within Yellowstone to enrich himself or other politicians?

Others objected to the fact that the park would take land away from honest settlers, undermining preemption rights which many white Westerners viewed as sacred. The 1862 Homestead Act had affirmed these rights of white Americans to claim and develop public lands. “The policy of setting apart so large an area of the public domain for the exclusive delights of the rich, shutting out actual settlers and cultivators is un-American,” one California newspaper argued.

On Jan. 30, when the Senate discussed the bill, Cornelius Cole, a Republican from California, echoed the objections several newspapers had made. Most of Cole’s Republican colleagues disagreed; the Senate voted on the bill without a roll call. A messenger was dispatched to walk across the capitol building to report that the Yellowstone bill had passed. Now it was time for the House of Representatives to do its part.

Read more: A Climate Change-Induced Landslide Is Wreaking Havoc on Denali National Park

On Feb. 20, 1872, Hayden submitted his preliminary report of the 1871 Yellowstone Expedition to the secretary of the interior. It contained sixty-four illustrations and specimen illustrations produced by the scientists. It also included five maps, progressing from single features (the White Mountain, or Mammoth Hot Springs) to the entirety of what Hayden already called “Yellowstone National Park.”

Hayden also wrote up a condensed version of his report to give to the House Committee on Public Lands, describing his discoveries and advocating for the Yellowstone Act. When the House convened on Feb. 27, the committee’s chair, Minnesota Republican Mark Dunnell, declared that they were in favor of preserving Yellowstone. The nine members of the committee even suggested saving more land than the 1,760 square miles originally proposed in the Senate. Their version of the park would encompass the entire Basin, not just the geysers.

As a national park, the committee insisted, Yellowstone would become a “resort for all classes of people from all portions of the world,” a democratic landscape of tourism that would prove the superiority of its features to any other site of sublimity across the globe.

Massachusetts Republican Henry Dawes stood up. The Chairman of Ways and Means and one of the most powerful men in the House, Dawes had voted to fund Hayden’s expedition. His son, Chester, had gone along as an assistant. In his speech, he mentioned the Yosemite precedent and argued that federal control of Yellowstone would not tread on settler rights—rather, it would preserve the remarkable features of this region and protect them from depredations.

He was interrupted at this point by John Taffe, a Republican from Nebraska and the chairman of the Committee on Territories. “I desire to ask the gentleman a question,” he said to Dawes, “and it is whether this measure does not interfere with the Sioux [Očéthi Šakówiŋ] reservation.”

If the Očéthi Šakówiŋ laid claim to the Yellowstone Basin under the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie, Taffe argued, no white settler could go into the land without their permission. This point was surprising. For most Americans and their elected representatives, Native land rights were nonexistent. The U.S. government and white citizens, most Americans believed, had the only land rights that mattered.

Dawes, who would later author the 1887 Severalty Act that took millions of acres of negotiated treaty lands from Indigenous nations to sell to white Americans, had no interest in this argument. The federal government always reserved the right to take reservation and other Native lands for its own purposes.

At this point, the question was called, the bill was read again, and the House voted. In the end, the vote was bipartisan but fell largely along party lines. Eighty-nine percent of Republicans present voted for the Yellowstone Act, and 70 percent of Democrats voted against it. The Republicans’ strong majority in the House meant that the Yellowstone Act passed.

On March 1, 1872, the Yellowstone Act was placed on President Grant’s desk in the executive mansion. Grant signed it, along with several other bills, with no statement or fanfare. But it was an auspicious moment for the nation, and for the history of conservation. The United States Congress had just created the first national park in the world.

Adapted from Saving Yellowstone: Exploration and Preservation in Reconstruction America by Megan Kate Nelson. Copyright © 2022. Available from Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com