When Micheal Cohen thinks back on his time at the Washington, D.C. jail, he recalls seeing so many cockroaches some nights “it looked like the floor was alive.”

The 43-year-old was detained from the summer of 2018 until April 2020, nine months of which he spent in the jail’s Central Detention Facility (CDF). The wall next to his bunk was covered in other peoples’ snot and slime, he says. “It was filthy.” There were always plumbing issues and the smell of sewage was constant, he says. And then there was the violence. He alleges that after he cursed at a corrections officer for refusing to turn on his water to flush his toilet, the officer beat him, handcuffed him and pepper sprayed him twice. He says he reported the incident, but the officer remained on staff.

“I thought I was going to die,” says Cohen, who now advocates for criminal justice reform in D.C. and the surrounding area. “The pepper spray stayed in my hair for months. Every time I took a shower it would trickle down my body and it was like I was being burned by acid.”

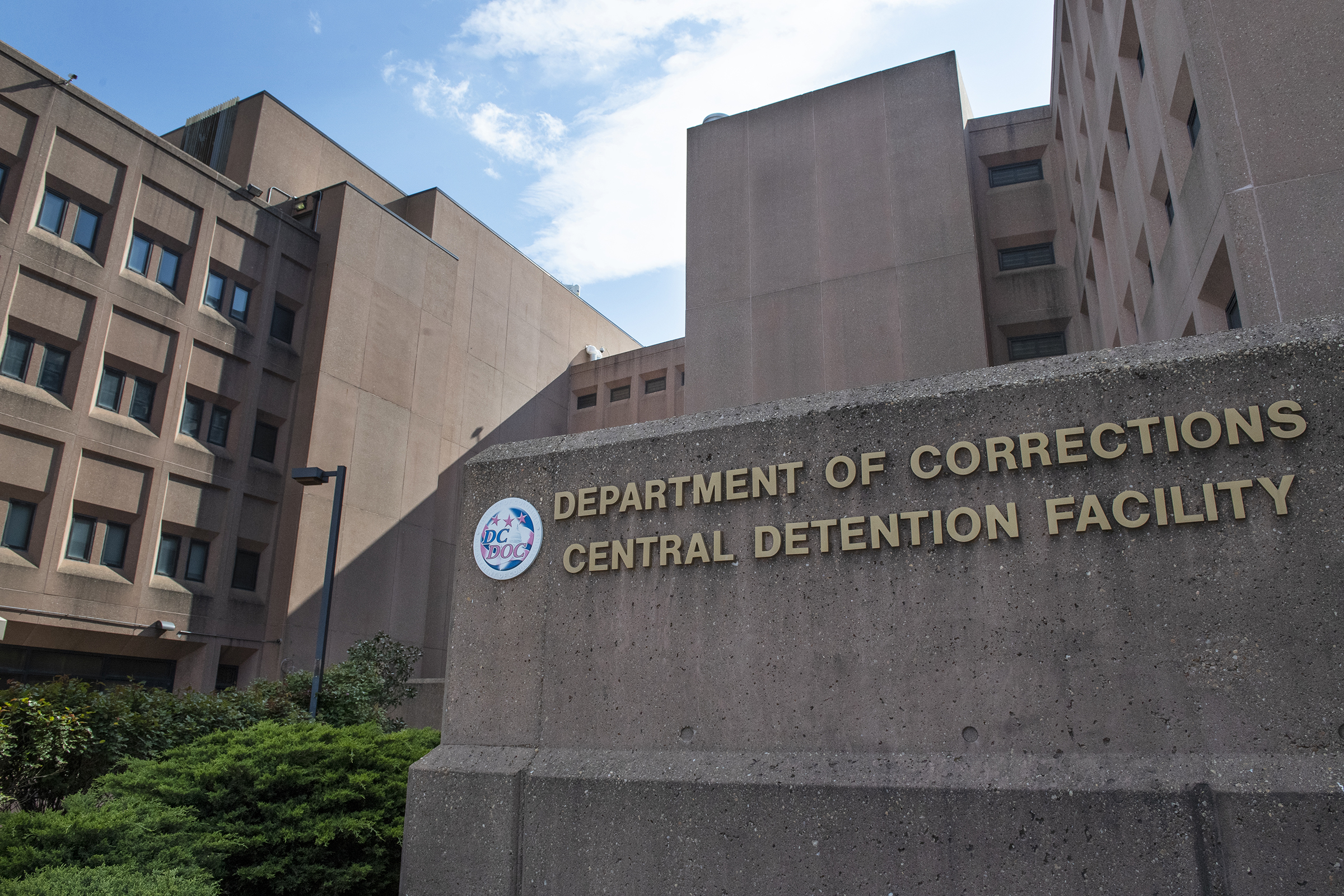

For years, advocates have raised concerns to the District of Columbia government over what they say are inhumane conditions inside the CDF, a nearly 50-year-old jail just two miles from the U.S. Capitol. Yet it was only when detainees accused of storming the Capitol building last Jan. 6 began raising complaints about the conditions of a neighboring jail facility that reform efforts gained momentum. After Jan. 6 defendants’ lawyers raised allegations of poor conditions at the Department of Corrections (DOC) facility, including a lack of access to medical care, an unannounced review of the jail by the U.S. Marshals Service (USMS) concluded there was “evidence of systemic failure.” USMS announced Nov. 2 that it would move 400 federal detainees out of the CDF to a federal prison in Pennsylvania.

Read more: For the Jan. 6 Rioters, Justice Is Still Coming

The D.C. government has promised to improve conditions at the CDF. But many argue the move comes decades too late, after repeated calls for change from the jail’s predominantly minority population. Demands for reform heightened during the onset COVID-19, as detainees were confined to their cells for 23 hours a day for over a year. But when white, non-D.C. residents—many of whom have received heavy media attention and found advocates in high-profile conservative lawmakers such as Rep. Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene—spoke up, action was taken, advocates say. On the evening of the Jan. 6 anniversary, dozens of demonstrators gathered outside the jail facilities to protest the conditions of the alleged rioters’ confinement. (The D.C. government was not available for an interview, and directed TIME to a clause in its agreement with the USMS that says neither party can comment publicly without the other’s consent. The DOC also did not respond to the specific allegations of conditions at CDF in this article.)

When Cohen, who is Black, saw that the Jan. 6 detainees’ complaints finally sparked change, he wasn’t surprised.

“It’s America. They’re not going to do anything unless white people say it’s a problem,” he says. “If the insurrectionists can be treated like humans, the people who’ve been in this city can be treated like humans.”

Decades of sounded alarms

Washington D.C.’s criminal justice system is—in a word—complicated. The District, which is not a state, once had its own prison system, but cut a deal with the federal government in 2000 when it fell into financial trouble. Today, the federal government handles functions normally left to a state, like imprisoning convicted felons, and D.C. government handles more local tasks, like running the jail that houses people charged with local and federal crimes, many of whom are awaiting trial.

CDF, which opened in 1976, has faced allegations of overflowing sewage, dirty water, inadequate medical care, unhealthy food conditions and widespread violence stretching back decades, says Jonathan Smith, executive director of the Washington Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights and Urban Affairs and a member of the independent District Task Force on Jails & Justice, which the D.C. city council formed in 2019 to examine the future of the jail.

“It’s just been a chronic problem, both in management and maintenance of that facility, since literally the day that it opened,” says Smith. “It’s been a failed and broken institution.”

Reports have flagged these problems for years. Smith’s Washington Lawyers’ Committee released a report in 2015 calling attention to “mold growth,” “water penetration through the walls,” “leaking plumbing fixtures,” and “deteriorating conditions” in the D.C. jail. In February 2021, the Task Force on Jails & Justice released a report calling for wide-spread changes, including replacing the CDF entirely and reducing the number of people detained at any given time.

“But the D.C. government didn’t act,” says Smith.

January ‘Sixers’ raise concerns

Then came the storming of the Capitol, and the arrests of people in the months after, charged with federal crimes ranging from obstruction of an official proceeding to assault. A year after the attack, federal prosecutors have charged more than 725 people with crimes in connection with the attempted insurrection. Dozens of Jan. 6 defendants are now being held in the D.C. jail in the specialized, lower security Central Treatment Facility (CTF) across the street from CDF.

Several of the so-called “Sixers,” as they’re known to their supporters, soon began raising concerns through their attorneys and families about the conditions of their confinement. Christopher Worrell, a member of the far-right Proud Boys group, had been detained in CTF after his March arrest on felony charges that included assaulting police. (Worrell has pleaded not guilty.) In May, Worrell, who had non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, hurt his hand while in jail. It needed surgery, his attorney said, but he could not go for the procedure since the DOC had not provided a doctor’s note to the USMS.

Months later, on Oct. 13, a federal judge held the DOC’s top officials in civil contempt for failing to provide the note. “It is more than just inept and bureaucratic shuffling of papers,” U.S. District Judge Royce C. Lamberth said at the time. “I find that the civil rights of the defendant have been abridged. I don’t know if it’s because he is a Jan. 6 defendant or not, but I find that this matter should be referred to the attorney general of the United States … for a civil rights investigation.”

Read more: What Happened to Jan. 6 Insurrectionists Arrested in the Year Since the Capitol Riot

Five days later, USMS began a surprise inspection of both CTF and CDF, prompted, it said, by “recent and historical concerns” that had been raised about the jail, including recent comments by judges.

In a memo released Nov. 1, USMS said they’d found “evidence of systemic failure,” particularly in CDF. The memo’s findings about the CDF included water and food appearing to be punitively withheld from detainees; “large amounts of standing human sewage” in the toilets of multiple occupied cells causing “the smell of urine and feces” to overpower; detainees in certain areas not being able to drink water, wash hands or flush toilets because water had been shut off for days; that DOC staff “confirmed to inspectors” that the cells’ water is “routinely shut off” punitively; that food delivery and storage was “inconsistent with industry standards; evidence of “pervasive” drug use; that DOC staff were observed “antagonizing detainees;” that detainees had “observable injuries with no corresponding medical or incident reports available to inspectors,” and that “supervisors appeared unaware or uninterested in any of these issues.”

The D.C. government disputes many of the allegations the USMS made about conditions at the jail, including that water has ever been denied to residents or shut off for days.

The USMS memo concluded that while CTF, where the Jan. 6 defendants are being held, met the minimum federal standards of confinement, CDF did not. On Nov. 2, USMS announced it would remove all of the detainees in CDF under its custody—roughly 400 people in total—to a federal prison in Lewisburg, Pa.

The USMS declined TIME’s request for an interview, but shared a Dec. 2 statement that said approximately 200 federal detainees had been transferred out of CDF, the majority to the Lewisburg prison as well as “other facilities in the region.” “Prisoners remaining in CDF have stayed in place for a variety of reasons, such as pending court-related matters, emergency stay orders granted by the court, and medical issues which prohibit transfer at this time, among others,” the statement said. USMS also said it was placing a “detention liaison” at CDF to monitor the facility.

Russell Rowe, a 32-year-old Black D.C. resident, had been detained in CDF since July at the time of USMS’s surprise inspection. He says he saw the same “deplorable” conditions the report alleges, and witnessed widespread violence, the constant smell of sewage and issues with flooding. He says if there was a fight, blood could remain on the floor for hours after. “Everything [USMS] reported, inmates had reported for the past 30 years,” Rowe says.

On Nov. 10, D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser and the USMS announced that they’d entered into a Memorandum of Understanding outlining how they would collaborate to improve conditions in CDF. But during a public roundtable that day, Deputy Mayor for Public Safety and Justice Chris Geldart said that while the D.C. executive realizes “there are some systemic issues that have persisted at DOC,” it does not believe they’re so pervasive that CDF is uninhabitable, and said the executive is against the transfer of detainees “over 200 miles away from their family support structure and attorneys.”

During the Nov. 10 roundtable, Geldart listed steps the DOC was taking to improve the facility, including inspecting all toilets and plumbing outlets, identifying “operational deficiencies,” and reviewing service requests. He said that while DOC denies allegations about water shutoffs, they have inspected pipes in the mentioned areas and strengthened policies regarding who turns off the water, as well as started having their food vendor deliver extra drinks with meals. He said that DOC will continue to work with its vendor to ensure all meals are provided according to industry standards, and is running training during roll call on “effective communication and customer service skills” for staff. He added that DOC is increasing the number of random contraband searches on units with smoke, and that his office is working to increase the Corrections Information Council’s (CIC) access and monitoring of the jail.

In all, Geldart said, the DOC fulfills around 200-250 work orders a month at the D.C. jail, over 80% of which are for clogged toilet pipes or sink drains. He acknowledged that the Department has faced staffing issues, which have been exacerbated by the long hours and tough work conditions amid the pandemic.

What happens now?

Most advocates argue none of this goes far enough to fix the serious problems at the D.C. jail—and it comes too late. “It’s like a bandaid on a gunshot wound,” says Anthony Petty, who was detained in the jail in the 1990s and is now a member of the advocacy group Neighbors for Justice.

Smith says the Task Force on Jails & Justice has received “no clarity into this reform effort,” and argues there’s “no meaningful oversight” of those efforts.

Some advocates say USMS’ decision to move hundreds of detainees to Pennsylvania is a quick fix that didn’t solve anything. Rowe was among those moved to Pennsylvania, before being transferred back to D.C. just a week later because he’d been enrolled in a program in CTF. In his opinion, too, moving the detainees was a mistake. The conditions in Pennsylvania weren’t much better, he says, and people who had yet to be convicted of any crime were taken away from their families and legal counsel.

Joel Castón, a commissioner on D.C.’s Advisory Neighborhood Commission 7F who was elected in June 2021 while still detained in the D.C. jail, agrees. “That was not a remedy,” Castón says. “If we felt that [CDF] was an inadequate space for [detainees], we should have allowed Washingtonians and our elected officials to come up with what we felt was our most viable option to fix that.”

Ultimately, most people who have been following conditions at the D.C. jail agree that the best solution would be to tear down CDF altogether, and build a new jail. Geldart said as much in the Nov. 10 hearing, adding that the D.C. executive is committed to working to determine the right location and budget for the project.

But building a new jail takes time. There were 937 detainees in CDF as of Dec. 24, and it’s unclear where they would go while that was happening. “That’s the million dollar question,” Petty says. “I don’t want to see detainees taken away from their families.”

In the meantime the jail continues to operate. Some detainees were complaining about sewage overspilling and flooding as recently as December, someone familiar with the inner-workings of the jail tells TIME, who spoke on the condition of anonymity.

When Rowe returned to CDF on Nov. 18 after his brief transfer to Pennsylvania, he says “nothing had changed at all,” and remained the same until he was released in mid-December.

As for Cohen, seeing reform efforts finally take shape years after his own experiences in detention has been infuriating.

“They should have fixed these problems a long long time ago,” he says. “It’s a slap in the face.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Madeleine Carlisle at madeleine.carlisle@time.com