If 2021 was one of our last, best, chances to save the planet, it was also the year that we bought lots and lots of stuff, cooped up at home and frustrated with the pandemic. That shopping acted counter to the goal of reducing our carbon footprint; consumption drives about 60% of greenhouse gas emissions globally, as the factories that make our stuff and the ships and trucks that bring it to us generate emissions, not to mention the emissions caused by mining for raw materials and farming the food we eat. Amazon alone reported in June that its emissions went up 19% in 2020 because of the boom in shopping during the pandemic.

Still, it can be hard, as an individual or a family, to care enough to change habits. Buying things has become one of the few sources of joy for many people since COVID-19 began sweeping the globe—and shopping online has become necessary for people trying to stay at home and avoid potential exposure. But goods are so cheap and easily available online that it feels harmless to add one more thing to your shopping cart. Convincing yourself to be environmentally conscious in your shopping habits feels a bit like convincing yourself to vote—obviously you should do it, but do the actions of one person really matter?

As I kept buying things that I thought I needed while cooped up at home, I wondered: how much was my shopping, individually, contributing to climate change? Those pairs of extra-soft sweatpants, those reams of high density rubber foam that I use to baby-proof my apartment, those disposable yogurt bins and takeout food containers, all made from plastic and paper and other raw materials; was I—and other U.S. families spending so much money on stuff—making it that much harder to reach the COP26 goal of preventing warming from going beyond 1.5°C?

Read more: Our Shopping Obsession is Causing a Literal Stink

In order to estimate the carbon footprint of the shopping habits of families like mine, I asked four families in four cities—Denver, Colo., Atlanta, Ga., San Francisco, Calif., and Salem, Mass.—to track their spending the week beginning on Cyber Monday, Nov. 29, so I could try to determine what parts of their holiday spending were most harmful to the environment. I chose to calculate their carbon footprint rather than other impacts like the amount of water used to make the products they bought because scientists agree on the urgency of reducing greenhouse gas emissions to protect the planet’s future.

Measuring one’s carbon footprint is difficult, especially because much of the environmental impact from spending is upstream, at the factories that burn fossil fuels to make cars, for example, and at the farms that raise cows for our consumption and release methane. So I asked for help from David Allaway, a senior policy analyst at the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality, who has been working for years to calculate the carbon footprint that comes from consumer spending. To figure out how much the consumption habits of Oregonians contribute to climate change, and what the state should be doing to remedy this, Allaway commissioned the Stockholm Environment Institute to produce the first state-level analysis of the environmental footprint of Oregon’s consumer spending in 2011.

This analysis, called consumption-based emissions accounting, roughly estimates the emissions that come from consumer purchases in 536 different categories, including things as specific as beef cattle, books, and full-service restaurants. It counts the emissions of all purchases by consumers, regardless of where those emissions were created—in Mexico, picking, packing, and shipping bananas; in Saudi Arabia, drilling for and refining petroleum. Allaway has refined the analysis since then and completed it again in 2015.

Allaway agreed to use the model he has honed to calculate the carbon footprint of these four families, based on how much money they spent in each category. The families sent me their expenses, excluding housing, and I entered them into the categories in Allaway’s model. This is, of course, an inexact model: The families only tracked one week of spending, and their spending was self-reported, so it’s possible they missed an expense or two. Still, the estimates give a good overview of the emissions driven by the behavior of different families.

They only tracked one week of spending, and I prorated their electricity and power costs, so this is still an inexact calculator. A family might spend a lot one week and not much the following week. Still, the estimates give a good overview of just how much of a difference individuals can make in reducing their carbon footprint, and they shed light on exactly how our spending drives emissions.

Although many consumers have a lot of guilt about disposing of things once they’re done with them, whether it be plastic packaging or a shirt that they’ve worn a few times and then stained, we just looked at consumption. That’s because the emissions from the disposal of goods is tiny compared to the emissions created from producing something in the first place. “By the time you purchase something, 99% of the damage has already been done,” Allaway told me. This means that the “reduce” part of “reduce, reuse, recycle,” is the most important.

Read more: How American Consumers Broke the Supply Chain

Buying less stuff is a piece of reducing emissions, but families can most reduce their carbon footprints through their eating and travel habits. The Denver family, which is vegetarian and has solar panels on their roof, had a significantly smaller footprint than the others. The families that ate beef and dairy and that bought plane tickets were responsible for the most emissions. There’s a reason the Swedish have a word “flygskam,” or “flight shame”: one flight can cancel out the most tightfisted family’s progress for a week.

In general, spending on services and experiences, like concert tickets or museum subscriptions, is more environmentally friendly than spending on goods, because part of what you are paying for is labor. Allaway estimates that every $100 spent on materials accounts for about three times more emissions than $100 spent on services. Of course, there are exceptions—spending $100 on a steak dinner for two could have higher emissions than spending $100 on groceries to make a vegan meal at home.

A few more quick caveats: these are all families with annual incomes of more than $100,000, and I sourced them from friends of friends and social media. They are all white, which is the group that is responsible for the highest levels of consumption in the U.S., and as a result, the most emissions. TIME agreed to use only their initials and the cities in which they live in order to encourage them to openly share their consumption habits without fear of being shamed for their purchases.

The results varied widely, from a family in San Francisco that had a weekly carbon footprint of 1,267 kg of carbon dioxide equivalent—about the same as driving from New York to San Francisco in a gas-powered car—to the family in Denver whose weekly carbon footprint was just 360 kgCO2, the equivalent of driving from Denver to Tucson. Here are their detailed weekly breakdowns.

The Family That Spends a Lot Online

A.S. + W.H.

Location: Salem, Mass.

Children: 1-year-old

Combined household income: about $200,000

Total emissions: 819 kgCO2e

This family spent about $2,800 for the week and had a carbon footprint of 819 kgCO2e, the equivalent of a passenger car driving 2,058 miles, according to the EPA’s Greenhouse Gas Equivalencies Calculator. That’s the same as they would have emitted from driving from Salem, Mass. to Charleston, S.C., and back.

A.S and W.H. own their home in the coastal community of Salem, Mass. and have a baby daughter. Before becoming parents, the couple was used to buying things and using them for years. But they’re finding that as their daughter grows, their pace of shopping has sped up.

“One of the things that makes having a baby so wasteful is that you need something, and when you need it, you need it urgently,” A.S. told me. “You need it for three weeks, and then you don’t need it anymore.”

Online shopping has been a source of contention for the couple; W.H. buys almost everything online, which his spouse thinks creates needless waste. The two have asked their extended family to cut back on buying goods and to gift them experiences or services instead, but relatives have been resistant to change.

Their biggest single source of consumption-based emissions from the week, 138 kgCO2e, came from buying stuff online. They spent $298.99 for gifts for two family friends: two subscription boxes from Little Passports, which will send the recipients crafts, puzzles and books about different locations around the world for a year. This falls into the “dolls, toys, and games” category, which means the emissions-per-dollar would have been calculated the same regardless of what dolls, toys, and games they bought. Most of the emissions in this category come from the factories that make this stuff, rather than the materials mined or produced to create them, Allaway said, so it wouldn’t really matter environmentally whether they bought these toys at Amazon, Walmart or at a local toy store. They also bought a $269.20 wall sconce, a purchase that created 105 kgCO2e.

Aside from those purchases, their biggest emissions came from the food they ate—specifically beef and dairy products. A.S. and W.H. had a pizza dinner with family during the week and a few snacks and coffees at local restaurants; all meals out, whether sit-down or take-out, are categorized as services. But they did buy around $40 worth of ice cream, yogurt and cheese, and they participated in a food share that provided them with around $28 of red meat (the protein changes every week.) Dairy and beef cause a lot more emissions than vegetables; the family spent roughly the same amount on vegetables and on dairy products, but the dairy was responsible for more than double the emissions as their veggies.

The couple told me that they’ve been trying to cut back on dairy but have had a hard time finding an environmentally-responsible alternative; almond milk uses up crucial water, for example, and coconut milk requires a lot of emissions-heavy transport to get from where coconuts are grown to New England. They also wonder whether cutting back on things they enjoy is worth the sacrifice. Spending $30 on beef produces about 47 kgCO2e, which is the same as driving about 120 miles. Why should they stop buying cheese if their neighbor is driving that far to commute to and from work every week? “That’s one of the big pieces of friction between me and my husband,” A.S. told me. “I think he sees this as too big of a problem for any individual behavior to change.”

The Family That Eats Out a Lot

M.C. and N.A.

Location: Atlanta, Ga.

Children: 14 months and 3 ½ years old

Combined household income: $100k-$200k

Total emissions: 757 kgCO2e

This family spent about $1,361 for the week and had consumption-based emissions of 757 kg CO2e, the same as if they’d driven a car 1,902 miles, according to the EPA’s Greenhouse Gas Equivalencies Calculator. That’s the distance from Atlanta to Las Vegas.

The Atlanta family’s emissions came in slightly lower than the Salem family’s. M.C. told me that this week was atypical for them because they usually buy diapers and fill up on gas, and they didn’t do either this week. They did eat out a lot—they were surprised by how much, once they started counting, but because of the way Allaway’s model works, restaurants are a lower-emissions way to spend money than buying a lot of goods. (The model doesn’t account for what you eat at a restaurant, but since so much of a restaurant’s bill is for service, rather than a tangible product, the spending often creates lower emissions.)

M.C. told me that because they’re in their car so much, they often stop by quick-service restaurants like Chick-Fil-A to get a fast dinner if they don’t have time to prepare something at home. The pandemic has made them feel guilty about the environmental repercussions of eating out so much, because even sit-down restaurants serve food on disposable plates, with plastic utensils.

But their biggest source of emissions for the week was something out of their control—electricity generation. Their electricity bill is about $200 a month but can be as high as $500 in the summer and winter, the family told me. I prorated that to $50 a week, which led to 254 kg CO2e, one of the highest single weekly sources of emissions for any family. (That’s the equivalent of a car driving from New York to Detroit.) The Atlanta and Denver households had higher emissions from their electricity and natural gas bills than the other two families in part because these regions are more reliant on coal-fired power plants, Allaway said.

N.A., who works in finance, takes public transit to work, and the family has been trying to move away from spending money on things and toward spending on experiences. But something like cutting back on red meat or being more conscious about the products they buy can be hard, M.C. said. She has enough going on already. “With two little kids, I don’t think about it,” she said.

The Family That Travels

A.A. and M.T.

Location: San Francisco

Children: 18 months

Combined household Income: more than $300,000

Total emissions: 1,267 kg CO2e

The wealthiest families create the most emissions, and that was certainly true with the San Francisco family, which was the highest-earning of the four families and which generated the highest emissions: the equivalent of driving from San Francisco to Miami. A.A. told me she thought the family had been buying way too much stuff online, and they did buy more stuff online than any of the other families —$60 on clothes from Target, $23 for a baby float on Amazon, $48 for diapers on Amazon, $21 for baby wipes. They also shopped at brick and mortar stores—$26 at a local bookstore, $37 at CVS for razors and snacks, $18 at a local hardware store. And they spent a lot on restaurants—about $300 in total.

But none of those purchases drove the bulk of their emissions. Instead, that came from a $400 purchase of two round-trip airline tickets from San Francisco to Los Angeles, which created 436 kg CO2e, the single largest emissions from any purchase of the four families for the week. Because prices were discounted when they bought the tickets, that’s probably a low estimate of the emissions from their flight; the emissions calculator run by myclimate, an international nonprofit, estimates that a roundtrip flight for two between those two cities would generate 614 kg of CO2e, more than the 333 kg the family would have created by driving. (Taking a train would have lowered their emissions further, but also would have taken 12 hours one way.)

They also spent $400 on hotel reservations, leading to 123 kg CO2e. This is intuitive—we all know that flying creates a lot of emissions. But it was illuminating to see just how much more it creates than other things do. That one trip to LA bumped the family’s emissions from 708 kg in the week to 1,276.

A.A. told me they haven’t flown much since the pandemic started and bought the tickets to attend a close friend’s wedding. In the last two years, they’ve flown far less than they did before the pandemic and before having children. Instead, they’ve stayed home and explored San Francisco, or driven to destinations within an hour or two. They say they feel lucky to be able to do that where they live and will think twice before buying plane tickets on a whim going forward, but that unless costs go up, it may be hard to resist a getaway.

The Family That Buys Used

M.C. and N.A.

Location: Denver

Children: 9, 7, and 4 years old

Combined household income: More than $200,000

Total emissions: 360 kg CO2e

The Denver family has been trying to be more environmentally-conscious for years, and they had the lowest emissions, despite having the most family members (although they were the only family without a kid in diapers.) Their emissions were far lower than those of the other three families, adding up to the equivalent of a drive from Denver to Tucson. They do just about everything they can do to reduce emissions: M.C. doesn’t eat meat or cook it at home; her husband and children only eat meat if it’s served at a friend’s house. The family tries to avoid dairy products (one of the items they bought this week was vegan “egg”nog); they buy used clothes from ThredUp; their home has solar panels.

M.C. said the family has always been conscious about reducing waste but became more serious about it a few years ago; when all their friends were moving to the suburbs, they moved to a more urban area of Denver, where N.A. could walk to work. “The driving we were doing was more impactful than the plastic wrap on a bag of pasta,” M.C. said.

The couple knew they would have to make some sacrifices when they had children, but they didn’t want to give up on their environmental goals. They decided to wrest control over what their life looked like. “We realized that we could make some more intentional choices, set up our life in a way that not only decreased environmental impact, but also made our life happier,” she said.

They enjoy being able to walk to so many places. M.C. has really never liked meat; she would occasionally cook it for her kids but stopped doing so three years ago. They’ll treat themselves to real cheese or real eggnog occasionally, but usually they go vegan.

Their biggest emissions came from their use of natural gas—they spend about $44 a month on natural gas, despite their solar panels. Because solar power is so variable—it may be sunny one day, and then cloudy for a week—most systems that run on renewables like solar also use some natural gas.

Still, the Denver family avoided a lot of emissions in places where other families didn’t. They spent $156 on clothes, but all from ThredUp, a used clothing site, which generated only 17 kg CO2e, according to Allaway’s estimates. The San Francisco family, by contrast, spent $61 on new clothes, which resulted in 26 kg CO2e. (Allaway’s model treats used goods as having a very low carbon footprint because it assigns the carbon footprint to the previous user, who bought them new; but buying used clothes does have some carbon footprint since the clothes are transported from the warehouses where they’re stored.)

M.C. said she knows her kids might resist wearing used clothes as they get older and that there may be a day when they don’t want Christmas gifts from the thrift store. But they’re trying to teach their children not to be consumed by materialism, she said. She wants them to find happiness from something other than new things.

When I asked M.C. if she thought her sacrifices were worth it, she said yes. Her family’s choices allow the couple and their children to focus on relationships, she said. She hopes she has motivated some friends and family to change their behavior, too. But ultimately, it’s about being aware of the urgency of environmental awareness, she said.

“By trying to reduce my own emissions, that helps me stay in touch with the broader issues and think about the ways I can be an advocate for change in the areas that really will have an impact,” she said.

What Your Family Can Do

Of course, the emissions that the Denver family saved compared to the San Francisco family would be wiped out by one individual taking an hourlong flight on a private jet. It can be hard to rationalize making dramatic behavioral changes when reducing individual emissions can feel fruitless. Even the annual emissions of the San Francisco family—around 66 metric tons of CO2—pale in comparison to the electricity use of just one U.S. supermarket over the course of a year: 1,383 metric tons of CO2. But changing your behavior is not fruitless, Allaway says. Individuals by themselves might not be able to make enough of a difference to prevent the worst effects of climate change, but collective action—lots of individuals working together—might.

Still, many of our preconceived notions about what to buy can be wrong. In the winter, Oregon consumers who buy tomatoes from nearby British Columbia have a bigger carbon footprint than those who buy tomatoes from faraway Mexico, because the Canadian tomatoes are grown in power-hungry greenhouses, Allaway has found. Out-of-season apples from New Zealand may have less of a carbon footprint than local apples that have been put in cold storage for months. Coffee beans delivered in a fully recyclable steel container have a higher climate impact than beans delivered in non-recyclable plastic because of the steel container’s weight.

There are behavioral changes you can make that will almost certainly lower your emissions. You can reduce your driving and flying. You can switch to renewable energy. You can buy lighter goods, which use less materials than heavyweight goods, and buy things that have to travel a smaller distance to get to your home (although that in itself is hard to parse out, because a “locally-made” toy may have been created from materials imported from China, which negates the benefits of buying something local). You can buy things that are made from plants rather than animals, and buy used goods whenever possible. (Of course, there’s a caveat there, too—buying a used car that is a gas guzzler would be worse than buying a new electric vehicle.)

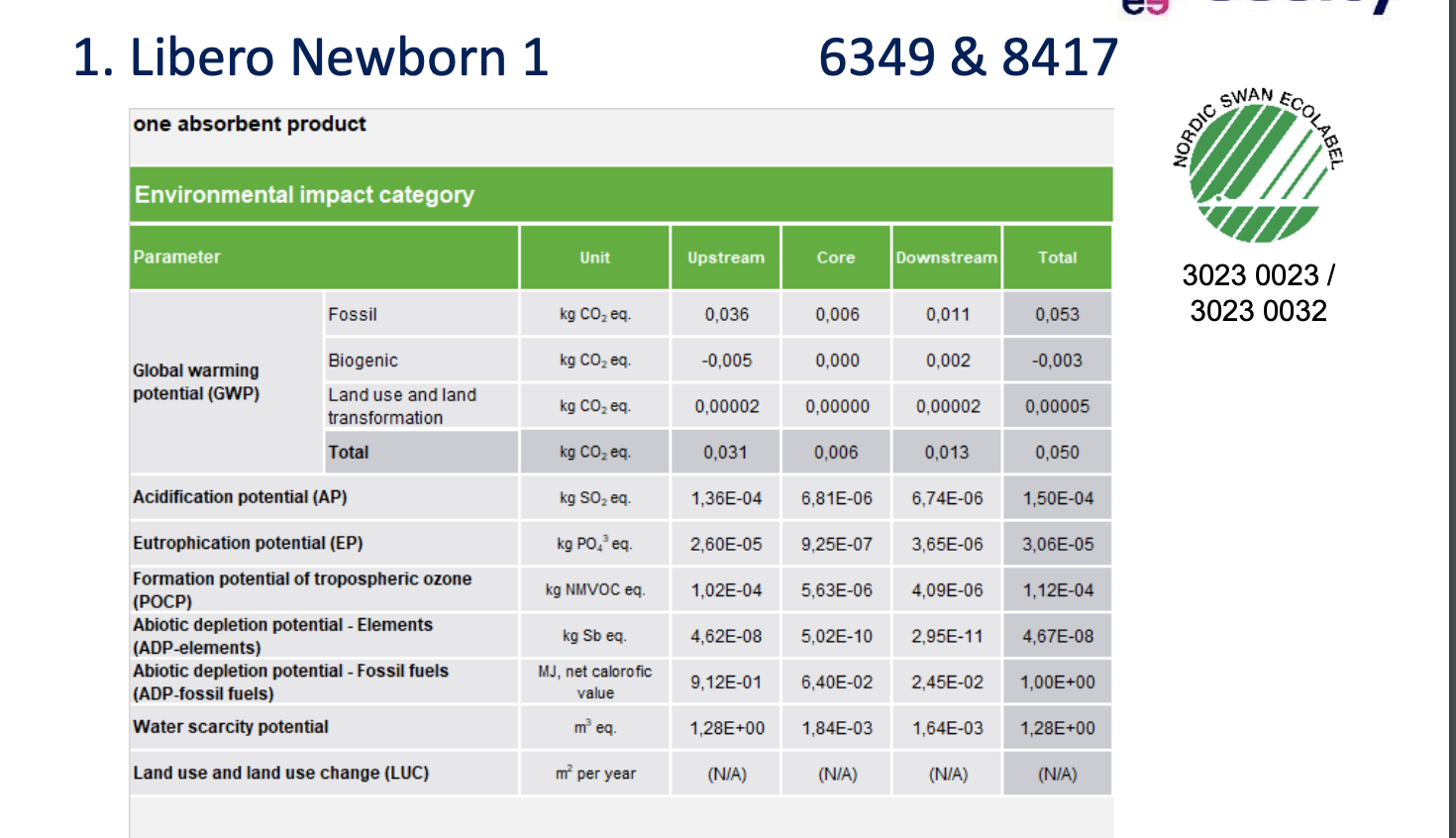

But if you’re trying to choose individual products that were created with lower emissions, you’ll have a tough task ahead of you. Right now, one of the only ways to know which products have the lowest carbon footprint is to read their life cycle assessment, which is a document that measures their environmental impact from cradle to grave. In Europe, many companies also offer Environmental Product Declarations, which are abbreviated versions of life-cycle assessments, says Sarah Cashman, director of Life Cycle Services at ERG, an environmental consulting group. These documents are hard to decipher, dotted with words like “eutrophication potential,” (the nutrient runoff from farming or manufacturing).

There is no report card that lets customers easily see which products are made, transported, and sold with lower emissions than others. Amazon has tried to start labeling some products as “climate-pledge friendly” so that shoppers can choose green products that have received a third-party sustainability certification from a qualifying organization. But even that puts a lot of burden on a consumer to read every label on every item that they buy. So much responsibility for creating less waste has already fallen onto the consumer that asking them to take one more step, as the families above said, is too much.

There is a solution, though. Consumers can demand more from companies, who can take on the responsibility of lowering emissions for the products they make every step of the way. The supply chains of eight global industries account for more than 50% of greenhouse gas emissions, according to the Boston Consulting Group. There are companies that already have a head start. Patagonia says that 86% of its emissions come from the raw materials it uses and their supply chains, and through its Supply Chain Environmental Responsibility Program, it is aiming to use only renewable or recycled materials to make its products by 2025.

Most companies won’t do this unprompted, but if consumers start shopping at places that are reducing emissions in their supply chain, companies will start looking at their supply chains in order to stay in business. A database of companies that are legitimately working on this would be a good first step. It may feel like there’s nothing you can do as an individual or as a family, but collective action could look like millions of families preferring to shop at places that are working to dramatically reduce emissions in their supply chain. Buying less may not be an option for many families, but Americans have proved, if nothing else, that they know how to shop smart.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com