The rule of law, democracy and human rights: these are the achievements of the modern nation state, or so we generally believe. Previous generations laid the ground with the Magna Carta, the U.S. Constitution, and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights—documents that we are taught set standards that even kings and powerful rulers ought to observe. But were these events quite as foundational as we think? And were the ideas they ushered in quite so revolutionary?

The notion that rulers should be held to account according to objective laws, that there should be rule of law, rather than rule by men, is ancient. It can be traced back to almost 2000 B.C.E. (before the common era), when a Mesopotamian warlord chipped a long list of laws onto a stone slab. Hammurabi was not the first ruler to make laws. But his laws, like his military conquests, were monumental. At the top of his granite stone (now in the Louvre in Paris) masons carved a portrait of the king receiving authority from the god of the sun. And the laws, Hammurabi declared, would ensure justice for all Babylonians for generations to come. He added a dramatic invocation to the gods to rain down pestilence, misfortune and curses on any later ruler who dared to contravene them.

Hammurabi’s regime, built on conquest and plunder, hardly provides a model for peace, democracy or human rights. But his colorful curses express the essence of the rule of law: that any ruler should be held accountable according to objective legal standards. We do not know how, if at all, his laws were applied by Babylonian judges, but even after Hammurabi’s successors lost power and Assyrian forces overran the region, Mesopotamians continued to refer to his laws. Scribes copied them centuries later as they learned their craft. The laws also inspired the tribesmen of Israel and Jordan, far to the west, whose priests copied some of their ideas when they crafted the laws of the Old Testament.

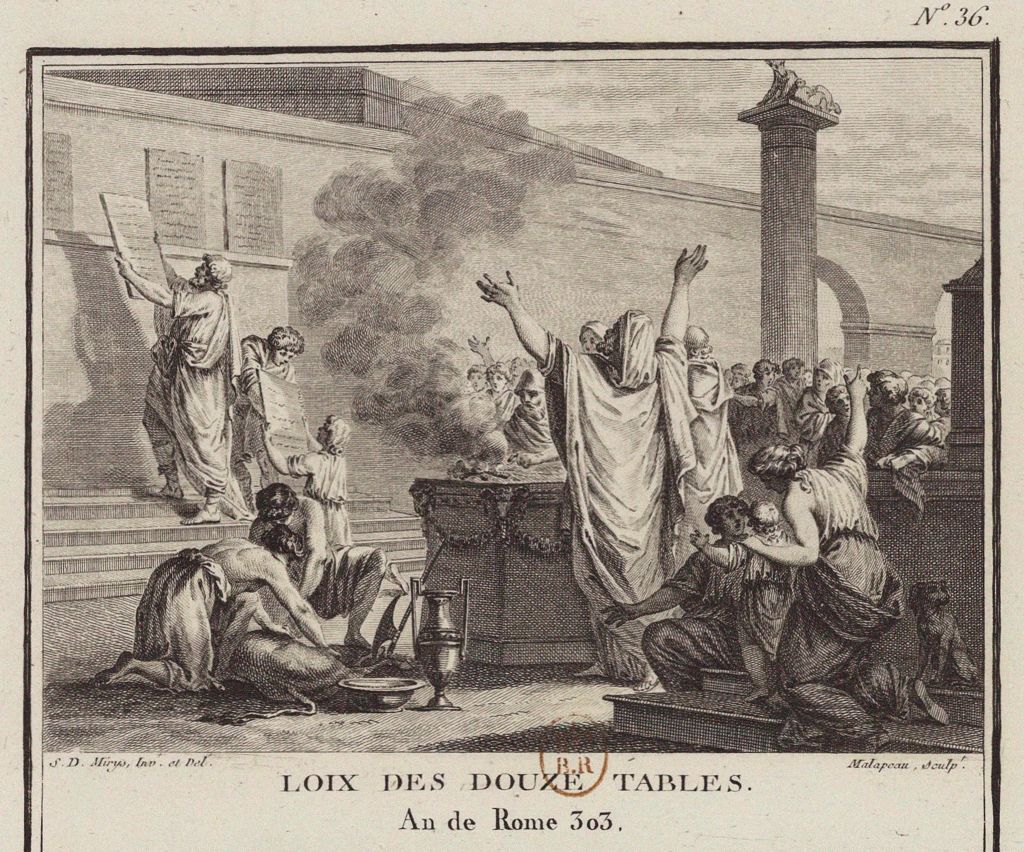

In around 600 B.C.E , the Mesopotamian tradition also inspired the citizens of Athens. They had just staged a revolt against tyranny and, in a quest to put their society onto a better footing, they commissioned a set of laws. Almost certainly copying Near Eastern precedents, the writers tried to spell out rights for ordinary people in laws that would give them protection against oppression. About a century later, the citizens of Rome, then still a minor city, also demanded laws. They had just mounted a revolt against their own oligarchs and formed an assembly to demand a new political order. The result was the Twelve Tables, a set of rules that adopted a similar form to the Mesopotamian laws. Etched onto bronze tablets the new laws were displayed in the Forum for all to see. The rather mundane rules largely concerned due process and relief from debt, but Romans came to think of them as the foundation of their social order. Over the next four centuries, Roman citizens gathered periodically in great assemblies to make new laws and used them effectively to curb the powers of the ruling elite and hold corrupt officials to account.

The Roman assemblies were huge and their processes cumbersome. They hardly formed an ideal model for the rule of law. But the Romans did insist that their officials should be held accountable to objective legal standards. And just before the turn of the first millennium, when the structures of the Republic came under threat from a new class of powerful military leaders—Mark Antony and Julius Caesar—the great orator Cicero warned of the dangers they presented to the authority and independence of the law.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

This was not the only tradition to develop the rule of law. Further to the east, Hindu priests were making laws that their kings were supposed to follow. The central Indian plains had long been ruled by powerful warlords but both political rulers and army generals looked to their priests to intercede with the gods and keep them safe. They respected the ritual specialists as guardians of ancient texts, the Vedas, and the priests gradually formed a hereditary class, the brahmins. Eventually, in the early decades of the first millennium, they wrote legal texts, the Dharmashastras, which told people of different classes how they should act in accordance with their dharma. This included rules that the kings should both follow and enforce. Gradually, the brahmins persuaded rulers all over the region to follow their ritual traditions. Even the most powerful came to accept that it was for the brahmins to declare what that law was.

More from TIME

In practice, Hindu kings generally consulted councils of brahmins when they had to decide difficult legal cases. In Kerala, one 18th-century ruler asked for guidance on how to deal with allegations of adultery and the brahmins obliged with an elaborately detailed set of instructions. The king, they said, had to appoint four investigators, including two brahmins, to consider the allegations. One expert should then go to the husband’s house and question the accused wife, while one of the brahmins hid behind a wall, his head covered by a veil. If the investigator made a mistake, the brahmin should silently drop his veil. The investigator should then report to the king, while the brahmin continued to monitor the proceedings, still using his veil to indicate disapproval. The process seems impractically elaborate, but the drama probably served to impress on everyone the seriousness of the allegations and the moral consequences of perjury. It was a Hindu answer to the universal problem of adjudicating on charges of sexual misconduct. And the brahmins were at the centre of it, independent authorities on the law.

In a similar way Islamic legal scholars set their expertise beyond the control of political leaders. Keen to ensure the support of the most respected scholars, the rulers of the early caliphates, which developed in the 7th to 10th centuries, established religious academies where scholars could develop their education. To this day, Muslims consult mufti, local legal experts, on tricky points of social conduct. And the highest religious and legal scholars, standing apart from politics, attract huge personal followings. In his seminary at Najaf in Iraq, senior Shiite cleric Sayyid Ali al-Husseini al-Sistani commands the loyalty of millions. Although largely reclusive, al-Sistani was persuaded to intervene during the American invasion of Iraq, calling for an assembly to be chosen in a general election, as opposed to an American-appointed body. Realizing his influence over Iraq’s Shiite population, the U.S. promptly altered its policy. Al-Sistani then successfully brokered a ceasefire before returning to his position of aloof authority.

Autocrats always try to avoid the rule of law, and often they have succeeded. But the Romans’ citizen assemblies, the brahmins’ texts and the aloof authority of the Islamic legal scholars, are just some of the means that people have used to hold their rulers to account. As we struggle to curb autocracy and power in today’s fragmented world, we may need to look beyond the familiar model of the democratic state. Many small communities still practice direct democracy and Al-Sistani’s intervention shows the positive influence religious leaders may have on geo-political events. History may not give us all the answers—Hammurabi’s curses are unlikely to have much effect today—but these examples remind us that there are many possible versions of the rule of law.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Contact us at letters@time.com