Emily Baldwin remembers the morning she realized that the COVID-19 pandemic was going to make her job more difficult. It was the spring of 2020, and the novel coronavirus was raging on the east coast but had yet to overtake West Virginia. A man rushed into the Milan Puskar Health Right clinic in Morgantown and said he thought there was someone dead in an alley about a block away.

Baldwin, who is a nurse and the coordinator for the clinic’s harm reduction program, ran outside and quickly realized a young man was overdosing. She sprinted back to the clinic, grabbed Narcan, a medication that can reverse overdoses, then raced back to the collapsed man. By the time an ambulance showed up, Baldwin was administering Narcan, but the EMTs wouldn’t walk down the alley to help.

“‘We can’t go near people like that’,” Baldwin recalls them saying. They seemed to be afraid the man might have COVID-19 and so kept their distance, she said, adding, “It kind of set the tone for the entire pandemic around here.” Over the past two years, situations like that—in which the opioid epidemic smashes headlong into the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic—have become frighteningly common, Baldwin says.

Deaths from drug overdoses have surged since COVID-19 first spread across the country in spring 2020. More than 100,000 Americans died from overdoses in the year from April 2020 to April 2021, a record number, according to provisional data from the National Center for Health Statistics. The majority of the deaths were linked to synthetic opioids such as fentanyl, signaling another worrying trend as the powerful, deadly substance has flooded the U.S. street drug market. West Virginia saw the second highest increase in overdose deaths of any state, with a jump of 62% from early 2020.

Read More: Fentanyl and COVID-19 May Have Made the Opioid Epidemic Even Deadlier

In addition to the changing drug supply, public health experts say the pandemic exacerbated addiction and overdose numbers because it cost millions of Americans their jobs, interrupted drug treatment programs, left people isolated in their homes without support networks, and worsened mental health across the country.

In the nearly two years since March 2020, community health centers, support groups, grassroots networks, and programs like the one in Morgantown, West Virginia have tried to help drug users stay connected and safe. But more than two decades into the opioid epidemic, those seeking to help are still grappling with small budgets, stigma and laws that can make their jobs difficult—all on top of a pandemic with seemingly no end in sight.

“It’s maddening to know how preventable it is,” says Baldwin. “It doesn’t have to be this way.”

‘It’s about just keeping people alive’

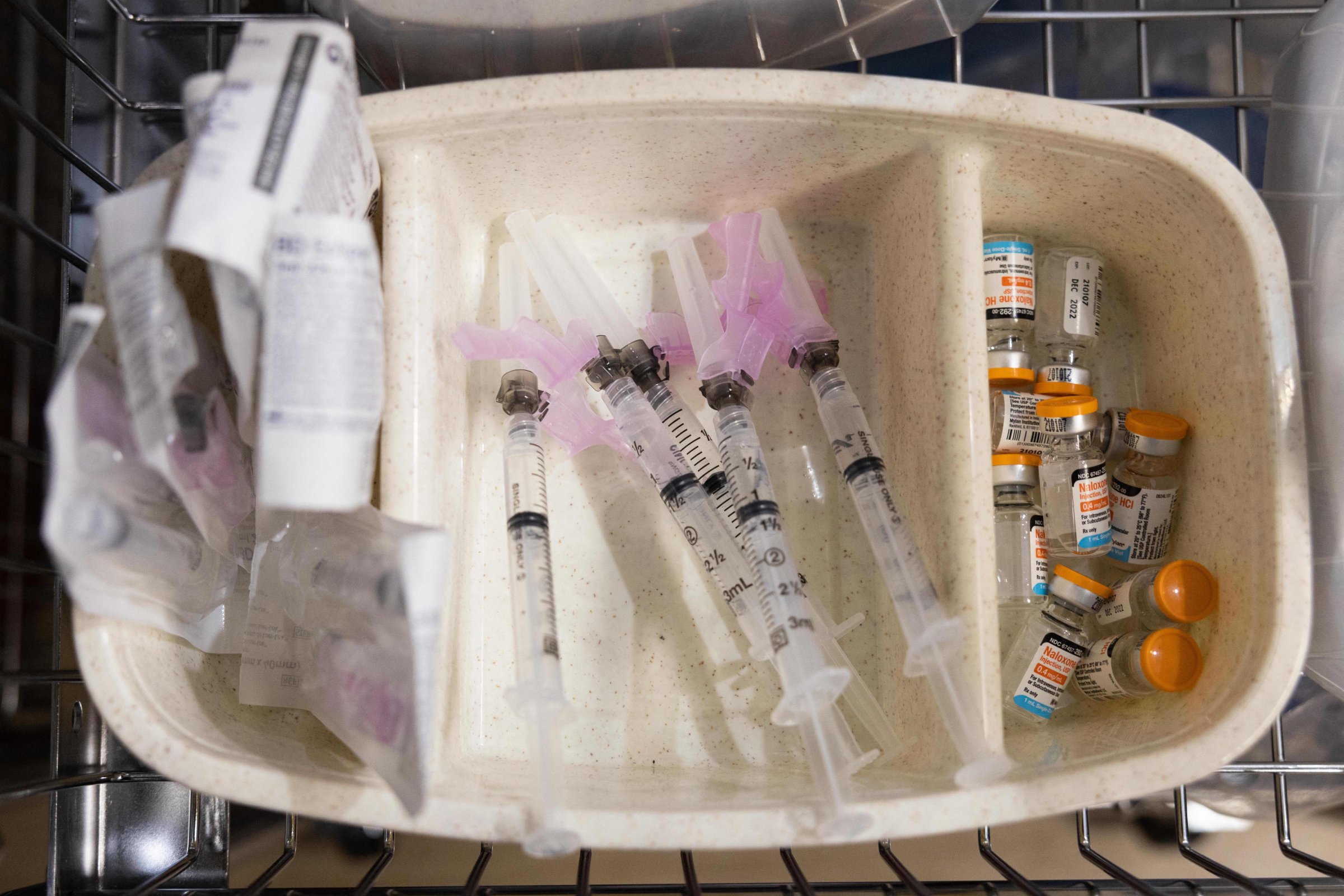

Baldwin runs West Virginia’s oldest program dedicated to what’s known as harm reduction, which means that instead of trying to help drug users attain abstinence, she and her colleagues are focused on trying to reduce people’s risk of dying or contracting infectious diseases like HIV. They provide sterile equipment, strips to test their drugs for fentanyl, naloxone to reverse overdoses, free medical care for wounds, peer support and even a safe place to spend time indoors. It’s all run out of Milan Puskar Health Right, a free health clinic for low-income and uninsured West Virginians.

While the clinic never fully shut down during the worst of the pandemic, it did make drastic changes that limited staff contact with clients and cost months of rapport-building—a crucial step that can help connect vulnerable people to HIV screenings, homeless shelters, treatment programs and opportunities to find food and other support. In some places, support groups or other programs for those with substance use disorder could move online. But the staff at Health Right couldn’t give out clean syringes or administer naloxone over Zoom, and for many of their clients who don’t have a permanent home, the in-person interactions are crucial.

Instead of offering each person a private meeting with a nurse, a peer recovery counselor, a social worker or a volunteer in an exam room as they would before the pandemic, Health Right staff began limiting the number of people who could enter the building and handing out supplies in their parking lot.

“We are the kind of place that, if you’ve been here before, we remember your name and we smile at you. And there’s a lot of hugging. But we haven’t been able to do any of that,” says Laura Jones, executive director of the clinic. For months, the staff focused on giving out sterile needles, naloxone and COVID-19 supplies like masks and hand sanitizer.

“It’s more about just keeping people alive,” Baldwin says.

Throughout the pandemic, Jones, Baldwin and their coworkers have worried when they haven’t seen their regulars in a while. “Sometimes we’re the only place they check in with anyone,” Baldwin says. “If we don’t see that person for a while, it’s like everything is up in the air. Where are they? Are they OK?” And as new waves of COVID-19 have continued, the limited rapport has also made it more difficult to help new clients navigate the pandemic in addition to substance use issues. “Without that rapport going into COVID, we didn’t have that trust to educate people about COVID,” Baldwin explains.

A political battle

The COVID-19 vaccines helped many services return this year, but then the West Virginia legislature passed a law aimed at cracking down on harm reduction programs like the one run out of Milan Puskar Health Right. State lawmakers concerned about finding used syringes in the community created a raft of new requirements that harm reduction programs will have to meet in order to keep operating next year. Health experts say many of the new rules are unnecessary and counter to CDC recommendations, but a lawsuit by Milan Puskar Health Right has not stopped the law.

“The belief in West Virginia is still very much that drug use is a moral failure, addiction is a moral failure,” Jones says. “So that was really demoralizing for all of us, because we know that to not be true.”

Under the new law, the clinic has to apply for a new license to operate the needle exchange program they’ve run for six years, start requiring West Virginia IDs from every participant, switch to only offering as many needles as each person brings back rather than giving out supplies on a needs-based system, and stop giving people needles they can bring to friends or family where they live. Several programs in the state have already closed because limited funds and staffing meant they were unable to adjust.

West Virginia has many neighboring states, including Pennsylvania, Ohio and Kentucky, where people travel from to get clean needles, so the ID requirement will mean far fewer people can get help, Baldwin says. The rural environment also means that limiting the number of needles people can take and prohibiting them from picking up needles for their community will be significant barriers. Participants often travel more than an hour to reach the clinic in Morgantown, and many don’t have their own cars. All of these requirements also mean the clinic will need more staff and new training for volunteers, further straining limited resources.

If fewer people can use her program, and others around the state are closing, Baldwin predicts dire consequences. “The naloxone access is less and people aren’t getting to touch base with anybody,” she says. “People are literally going to die because of this law.”

Read More: The Opioid Diaries: Photos from the Opioid Epidemic in America

Other cities like Charleston have had overwhelming HIV outbreaks in the past few years, while Morgantown has largely avoided this—something Baldwin and Jones say may be due to easy syringe access. Without that, other towns could see outbreaks as well.

Girding for a tough winter

Normally in December, the program’s three staffers would be focused on giving out flu or COVID-19 vaccines, helping homeless patients find shelter out of the cold or even helping plan the holiday party to bring the staff together. But the past few weeks have also been filled with mountains of paperwork and rewriting policies to ensure they are in compliance with their state’s new law. As Christmas approached, they were still waiting to hear back about their license to operate the harm reduction program, so they started giving out extra supplies to people in case they had to temporarily pause operations come Jan. 1. Then, near the end of the day on Dec. 23, the license came through.

Jones and Baldwin both express frustration that as the pandemic continues, it’s only going to get even more difficult to help the people who need their program. But even with the third year of COVID-19 approaching and the West Virginia law’s requirements taking effect, they are committed to serving as many people as they can.

“The thing that has kept me going for 30 some years in West Virginia is just the belief that health care is a human right and that it can manifest itself in a lot of different ways. Housing is health care. Harm reduction is health care. Emotional and mental health is health care,” Jones says. “I have worked really hard to find people who work here who have that same belief and that same mission. The team works equally as hard. There’s no one here that isn’t sacrificing a little bit of mental health or personal time with family to make sure that what we do can continue.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Abigail Abrams at abigail.abrams@time.com