Dave Horesh always liked the nice round prices on his company’s website: $25, $50, $100 for custom-made fabric banners and pennants in a rainbow array of felts. But by October, vendors for materials like thread, felt, ink and brass grommets had raised prices multiple times in the course of the year, turning a “slow drip” of increased costs into a troubling conundrum. So co-founder Horesh and the rest of his team at Oxford Pennant finally agreed: those nice round numbers were going to have to change. “When you get the right margins, you can absorb a 5% increase here, if the cost of thread goes up by 4%, whatever,” he says from his converted-attic office at his home a mile-and-a-half from his company’s factory in Buffalo, New York. “But when it happens across your entire supply chain, you can only resist it so long.”

They crafted an upbeat message to share the bad news with their customers through email and social media in October 2021. “Darn it! Almost all of our material suppliers raised their prices this year,” part of their copy read. “Price increases suck, but we’re dedicated to making it with US-sourced materials, right here in our hometown of Buffalo, New York.” Today, an Oxford Pennant custom banner that once went for $50 is now listed for $60. And business is actually up—Horesh says the feedback was “spectacular,” and the holiday season rush has been strong. “The pricing piece has been a net positive,” he says.

For small business owners like Horesh, the pandemic has meant not only navigating supply chain challenges during record work stoppages and labor shortages, but also keeping up with raw materials price increases and economy-wide inflation. Instead of subtly upping prices and hoping consumers wouldn’t notice, however—long the industry standard for consumer goods—many brands are finding that it pays to tell their consumers what’s going on in advance, as a way to gain trust (and avoid that “one killer Instagram comment,” as Horesh phrases it.) From fashion brands like Cult Gaia and Girlfriend Collective to monthly subscription services like shaving company Billie and butcher delivery service Porter Road, companies are choosing honest communication about the pressures that have changed their price tags. In the long run, that may well pay off.

And when it comes to this year’s upward trend in consumer prices, the rises are likely here to stay. It’s “less transitory as time goes by,” says David Ball, president of retail consulting firm The Grayson Company. “Unfortunately, retailers and consumer packaged goods companies often approach price increases in a stealth mode,” he says. While some companies just raise prices, the trend of “shrinkflation”—keeping the price the same but giving customers less product for that cost—has also gained steam.For example, this year, a package of Hershey Chocolate Kisses may cost the same as last year, but the package weight has dropped to 10.1 oz. from 11 oz., “effectively a 9% price increase in disguise,” Ball says.

CEOs of bigger companies may feel comfortable with this sly tactic, but not so for those of brands like Oxford Pennant, which built authenticity and consumer-facing friendliness into its DNA. When Horesh sent the email and social media blast out in October, he made sure its tone matched the company’s irreverent branding. “We just felt that the right strategy was a PR communication strategy that was inclusive and helped our clients understand our reasoning,” says Horesh.

Portland-based chai tea distributor One Stripe Chai chose a similar tack when across-the-board increases in the cost of inputs—spices, cardboard, paper products—meant they finally had to bite the bullet and pass some of that cost on to the consumer. They did so in November 2021, ahead of the holiday season, sharing the update in an email blast at the same time as they launched their website. (“We didn’t want to do this, but in order to run a more sustainable business, we have to make sure our prices reflect internal price increases as well,” a note read.) By now, says CEO Farah Jesani, price hikes seem ubiquitous.

Jesani started leading One Stripe Chai full-time in 2018 after leaving a New-York-based job in tech consulting, but the business only went direct-to-consumer when the pandemic forced a rethink about their buyers. (Wholesale buyers were, understandably, slim on the ground during shutdowns.) “We had never really increased our prices ever,” says Jesani. But the spikes of the past year were “insane,” making it unsustainable for them to continue eating that cost. The challenge of sourcing specialty Indian spices and dealing with long-distance deliveries further messed with their timelines. They bumped up the cost of a bottle of their chai concentrates by a dollar or two, and removed free shipping. “It’s going to help, but it’s definitely not going to cover all of it,” Jesani says. “As a business owner, you’re on both ends of it, because you’re a vendor, but you’re also a customer.” Still, she says, the saving grace has been the knowledge that these crunches are universal.

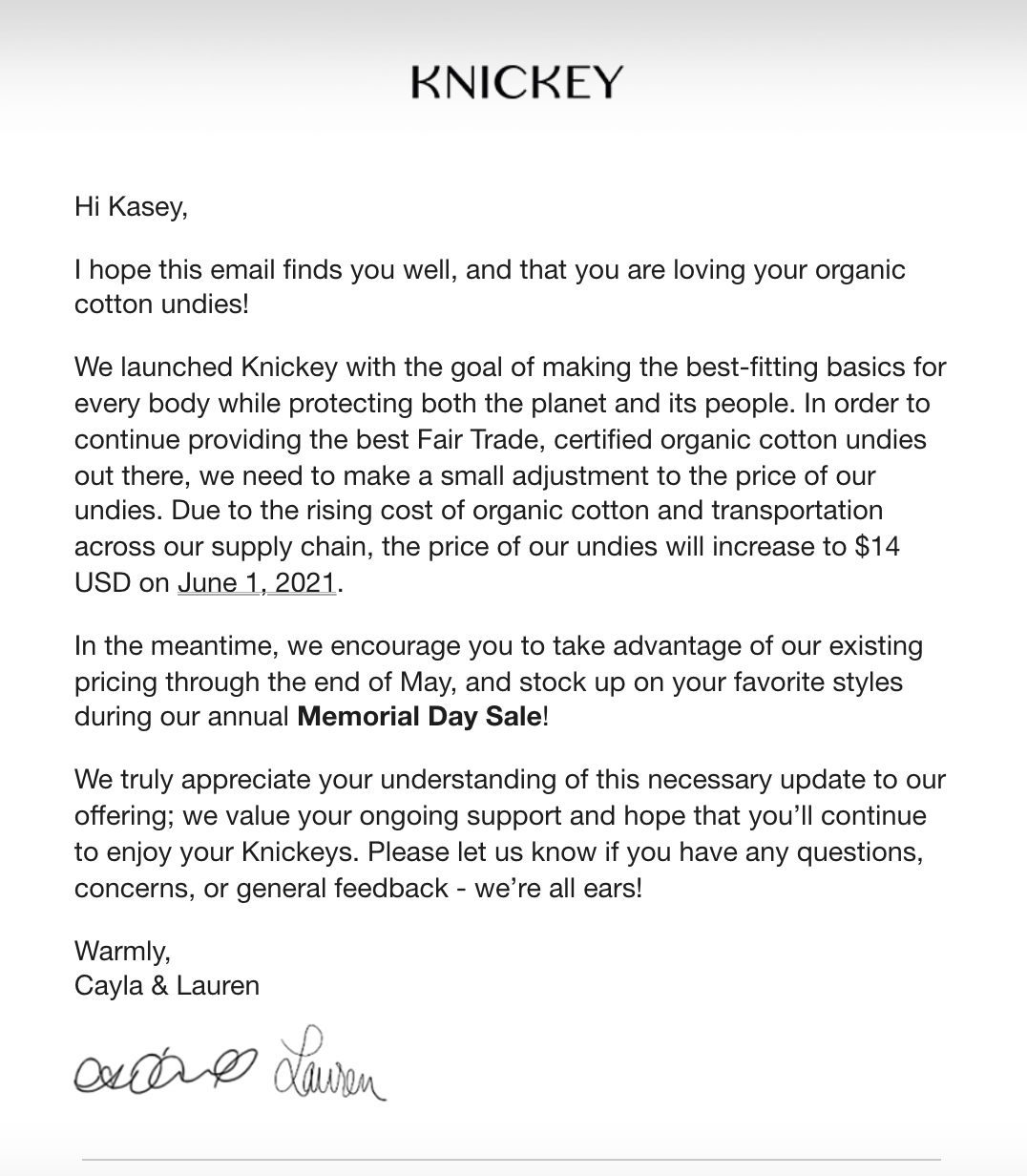

New York designer Cayla O’Connell has been dealing with the slow rise in materials costs for years. The co-founder and CEO of Knickey, a sustainably-sourced underwear brand, O’Connell has been committed since 2015 to using only organic cotton. In the past year alone, the price of her fabrics has gone up over 100%, she says, as organic cotton has gotten increasingly popular in the retail industry—and as supply chain and shipping challenges have come into play, as she sources her fabrics from India. It’s a cost she’s had to pass along to the consumer in order to balance her bottom line while maintaining her standards. “As a company that prides itself on being transparent and practicing what we preach, we went directly to our customers, we told them about it in May,” she says. In an email entitled “Important Announcement,” they shared the news: “In order to continue providing the best Fair Trade, certified organic cotton undies out there, we need to make a small adjustment to the price of our undies.” They cited the higher costs of their cotton and transportation across the supply chain.

But like Jesani, even that measure hasn’t solved it—despite good feedback from customers who understood the change, which hiked a pair of undies up to $14 a pop. (Her newsletter announcement even received an impressive 50% open rate.) “It’s still a problem,” she says. “In Q4, we saw even more inflation, like we haven’t seen in decades—so this is sort of an evolving issue that we are continuing to have to grapple with as a company.”

More from TIME

One thing all three business owners had in common: an overwhelmingly positive response from their communities of consumers. Horesh is having the best sales year ever. Knickey’s sales volume doubled in the past year. “No one has said anything, no one’s complained,” says Jesani, still seeming slightly surprised. “They seem to be totally okay with it!” O’Connell has had a similar experience: “Companies usually expect attrition or backlash, either in sentiment or in the bottom line,” she says. “And we had the opposite experience. That just really goes to show you where consumer sentiment is evolving around investing with their dollars in companies that they believe in [in terms of their] ethos, and are mission-led.” Meanwhile, products like Hersheys Kisses may just keep shrinking, quietly, in size.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Raisa Bruner at raisa.bruner@time.com