Worry about the concentration of wealth and power achieved by monopolistic—or potentially monopolistic—entities have always been wrapped up in each respective era’s technological innovations. It is not surprising then that the focal point of today’s debate around antitrust reform is the size and scope of internet giants like Google, Facebook (Meta Platforms, Inc.), Amazon and Apple—the pioneers laying the digital “railroad tracks” that have upended communication and commerce and, not coincidentally, allowed these companies to grow very, very powerful.

The history of antitrust legislation in the U.S. stretches back to the Second Industrial Revolution in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when transcontinental railroads bridged the coasts and ushered in a new era of mobility for both people and goods—along with concern about the formidable size and scope of these entities as they expanded, and then consolidated, to encompass entire industries.

The Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 made monopolies and trusts illegal. More than two decades later, the Clayton Antitrust Act of 1914 expanded the Sherman Act by prohibiting business activities, such as price discrimination, that companies could use to lay the groundwork for monopolistic practices.

Historically, policymakers primarily viewed antitrust legislation as a tool to keep big companies from muscling out smaller competitors, but that began to evolve in the 1970s. Since then, the governing principle of antitrust law has been the “consumer welfare standard.” When rival companies have to compete for the same pool of customers, it incentivizes them to improve their products and keep prices low, both of which benefit consumers, the standard says.

In principle, antitrust experts say Justice Department (DOJ) and Federal Trade Commission (FTC) officials have the tools to expand oversight and tighten requirements around activities like mergers and acquisitions that could be anticompetitive. In practice, however, a June report by Beacon Policy Advisors found that officials are constrained by a framework of permissibility implicit in the consumer welfare standard and a conservative judiciary inclined to defer to that paradigm. Pointing to the constraints and the growing influence of Big Tech, particularly since the start of the pandemic, many argue the consumer welfare standard is insufficient or inadequate, with calls for antitrust reform coming from the White House and, at varying levels, members of Congress.

“One group of antitrust activists really are arguing for enforcing the laws in a radically different way than they’ve been enforced for the past 40 years,” says William Kolasky, partner in the Washington, D.C. office of Hughes Hubbard & Reed.

Biden’s aggressive approach

Since taking office, President Joe Biden has signaled plans to seize on the building momentum for major antitrust reform. Biden tapped antitrust scholar and Big Tech critic Lina Khan to lead the FTC, putting a proponent of more robust antitrust regulation in charge of the agency—along with the DOJ’s Antitrust Division—on the front lines of antitrust compliance.

“Khan has indicated she really wants to transform the way the FTC enforces antitrust law. The extent to which she’ll be able to do that in a way that passes muster with the courts, we don’t know yet,” Kolasky tells TIME.

Along with Khan, the White House has sought to fill other key antitrust policy roles with Big Tech critics. Biden tapped anti-monopoly legal crusader Jonathan Kanter to serve as assistant attorney general for the DOJ’s Antitrust Division—a nomination that is expected to receive Senate confirmation—appointed Tim Wu, a Columbia University law professor who has compared today’s economic disparities to those of the late-19th century Gilded Age, to the National Economic Council.

Those advocating for a more robust antitrust regulatory framework are pushing for the use of a different set of criteria to determine just how big is too big. In a July executive order, Biden took on Big Tech along with other major industry sectors, saying consolidation enriched corporate honchos and foreign interests at the expense of ordinary Americans.

“Robust competition is critical to preserving America’s role as the world’s leading economy,” the order says, citing examples in agriculture, health care, telecommunications, financial services and global shipping in which there is a dearth of competition.

The executive order calls for marshaling a “whole-of-government” response and establishing the White House Competition Council to reorient American economic priorities to cultivate greater competition.

The Administration has “basically directed the agencies with jurisdiction over antitrust enforcement to be very aggressive,” according to Jonathan Osborne, a business litigation shareholder at Gunster, a law firm. Osborne says this standard would apply to mergers and acquisitions that could lock current—or even future—competitors out of a given market.

Biden’s strong support of unions and organized labor also has antitrust implications. The coalition his White House is building will consider the impact on people not just as consumers, but as workers as well.

What’s happening in Congress?

Monopolistic power is a worry that sometimes makes strange bedfellows, especially in Congress. But there is momentum for antitrust reform on both sides of the aisle.

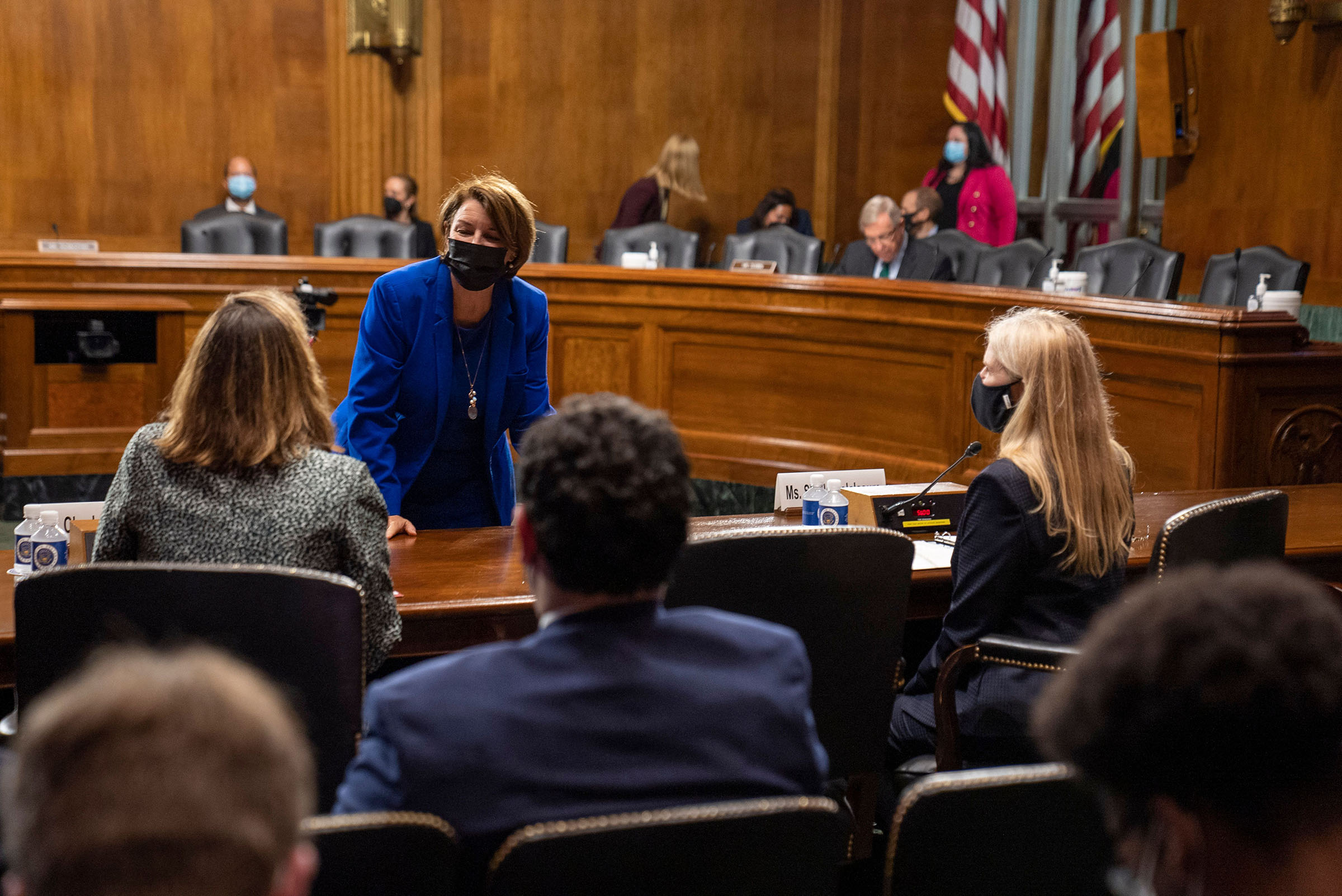

Following the House Judiciary Committee’s passage of a package of six antitrust bills in June with bipartisan support, Sen. Amy Klobuchar (D-MN), chair of the Senate Subcommittee on Competition Policy, Antitrust, and Consumer Rights, advanced Senate versions of some of those bills with Republican colleagues.

Klobuchar and Arkansas Senator Tom Cotton, a Republican, last week introduced the Platform Competition and Opportunity Act. The legislation would make it harder for Big Tech to acquire rival companies. Under current law, regulators seeking to block proposed mergers must prove they are anticompetitive. The Klobuchar-Cotton bill would shift the burden to Big Tech companies, who would have to prove an acquisition or merger wouldn’t stifle competition.

Last month, Klobuchar and Iowa Senator Chuck Grassley (R), the ranking member of the Senate Judiciary Committee, introduced the American Innovation and Choice Online Act, a bill that would prohibit big technology platforms from giving their own products and services preferential treatment, such as moving their products or services to the top of search results.

Read more: Facebook’s Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Week — And What It Means for Antitrust Reform

Klobuchar also introduced the Merger Filing Fee Modernization Act, which the Senate passed in June. The legislation—a version of which has cleared a key procedural hurdle in the House of Representatives with some level of bipartisan support—would increase funds allocated to the FTC and the DOJ Antitrust Division.

Despite the rare display of bipartisan coordination, the Senate and House —and members of both parties—have somewhat differing priorities when it comes to creating new laws aimed at thwarting monopolistic corporate power. Republicans want to rein in what conservatives view as big tech companies’ chokehold on political speech and, ultimately, free speech. Democrats are focused on, at the very least, constraining these companies’ ability to expand, with some—including members of the Biden team—calling for breaking up technology giants.

The focus on Big Tech

The heightened focus on Big Tech took on new urgency during the pandemic. As constraints on business and social activity forced Americans to rely more on digital platforms for communication and commerce, tech giants became more prominent, more profitable and visibly more powerful.

“COVID underscored their significance. The good story for them is they became lifelines of goods and services. The bad news was that their importance and those lifelines became more evident,” says William Kovacic, professor of Law and director of the Competition Law Center at George Washington University.

Antitrust reform advocates say Big Tech companies don’t need to be monopolies in order to stifle smaller competitors because they have an asset that gives them a critical competitive head start: access to data on millions and millions of people who use their products.

Read more: Facebook’s Antitrust Victory Could Inspire Congress to Overhaul the Rules Entirely

In shaping how people wrestle with issues of law and culture, Big Tech also has “an outsized political significance,” Kovacic adds. “That’s why you have this interesting coalition of Democrats, who have stronger preferences for intervention, and conservative Republicans who, for the moment, despise Big Tech.”

Data privacy issues have also driven the heightened interest in big tech. While antitrust law was initially only focused on price and output, today it also is concerned with consumer data privacy—a topic experts say very much pertains to the question of consumer welfare and the inherent value of their personal data to big technology firms.

Some legal experts worry that focusing on technology firms could backfire. “For a very long time, antitrust laws prided themselves on being industry-agnostic,” says David Reichenberg, an antitrust litigator.

According to Reichenberg, the danger in writing bills that target a certain industry rather than problematic practices can make the laws unwieldy and hard to apply, especially in the face of rapid advances in computing power that is continually redrawing the boundaries of what it means to be a technology company. “The reason people have resisted industry-specific legislation for so long is it’s hard to administer, it’s hard to predict scenarios and know what’s going to harm consumers. We need laws that can adapt to the facts,” Reichenberg says.

Tech companies argue legislation like the Platform Competition and Opportunity Act would stifle competition, especially on a global scale, and investments.

Antitrust critics have also taken aim at other proposals, arguing that legislation targeting Big Tech could hurt the consumer experience. A nonprofit consortium of industry-affiliated groups signed a letter warning that under a bill in the House, tech giants could be forced to splinter their offerings and saddle consumers with less seamless, more expensive online services. The letter suggested that Google might have to strip its map feature out of its search engine, Apple’s iOS would be forced to peel off functions like iMessage and FaceTime and Amazon would have to scrap its Prime subscription service.

But legal experts dismiss these arguments. “I have some skepticism that any legislation that passed would have those kinds of draconian effects,” Kolasky says.

While technology is clearly in the cross hairs of the antitrust reform movement, other big industries from agriculture to biotechnology also are likely to face heightened scrutiny—and the Democrat-led executive branch isn’t willing to wait while lawmakers hammer out their differences. A partnership between American Airlines and JetBlue Airways that would consolidate the operations of the two carriers in New York City and Boston, for example, is the target of a lawsuit filed last month by the DOJ and the attorneys general of six states as well as Washington, D.C. Earlier this month, the DOJ filed an antitrust suit to block publishing giant Penguin Random House from acquiring rival Simon & Schuster.

Whether in the halls of Congress or through the executive branch, it seems clear that business and industry titans face a once-in-a-generation moment of reckoning that all signs suggest will be significant in scope.

“What the laws are supposed to do is incentivize them to continue to be successful, without the harmful effects,” Reichenberg says.

Reform advocates across the political spectrum are staking their convictions on the belief that removing barriers to competition will help level the playing field, benefitting small firms and start-ups. “I think that the left is saying this is synonymous with economic opportunity,” he says.

Ultimately, Reichenberg says what Congress and policymakers have to wrestle with is defining the law’s role as gatekeeper. “What all these laws are about is, through what lens are we evaluating if something is good or bad?”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com