On a morning Zoom call, a group of Canadian mothers give their full attention to a young man from the Drug User Liberation Front. At 26, Jeremy Kalicum is the age some of their kids would be if they had not died of accidental overdoses.

Kalicum’s tone is urgent as he walks the moms through a PowerPoint presentation explaining why the Liberation Front, known as DULF, wants to protest on International Overdose Awareness Day and hand out illicit drugs. These wouldn’t be the kind that killed their sons and daughters, he assures them; they’d be “safe supply” drugs that have been tested to ensure they’re not laced with lethal fentanyl. “Anyone who wants to find drugs can find drugs,” says Kalicum, reasoning that the best way to save lives is to make sure users are given the safest possible drugs. “The drugs that they’re finding are of unknown quality and unknown potency.”

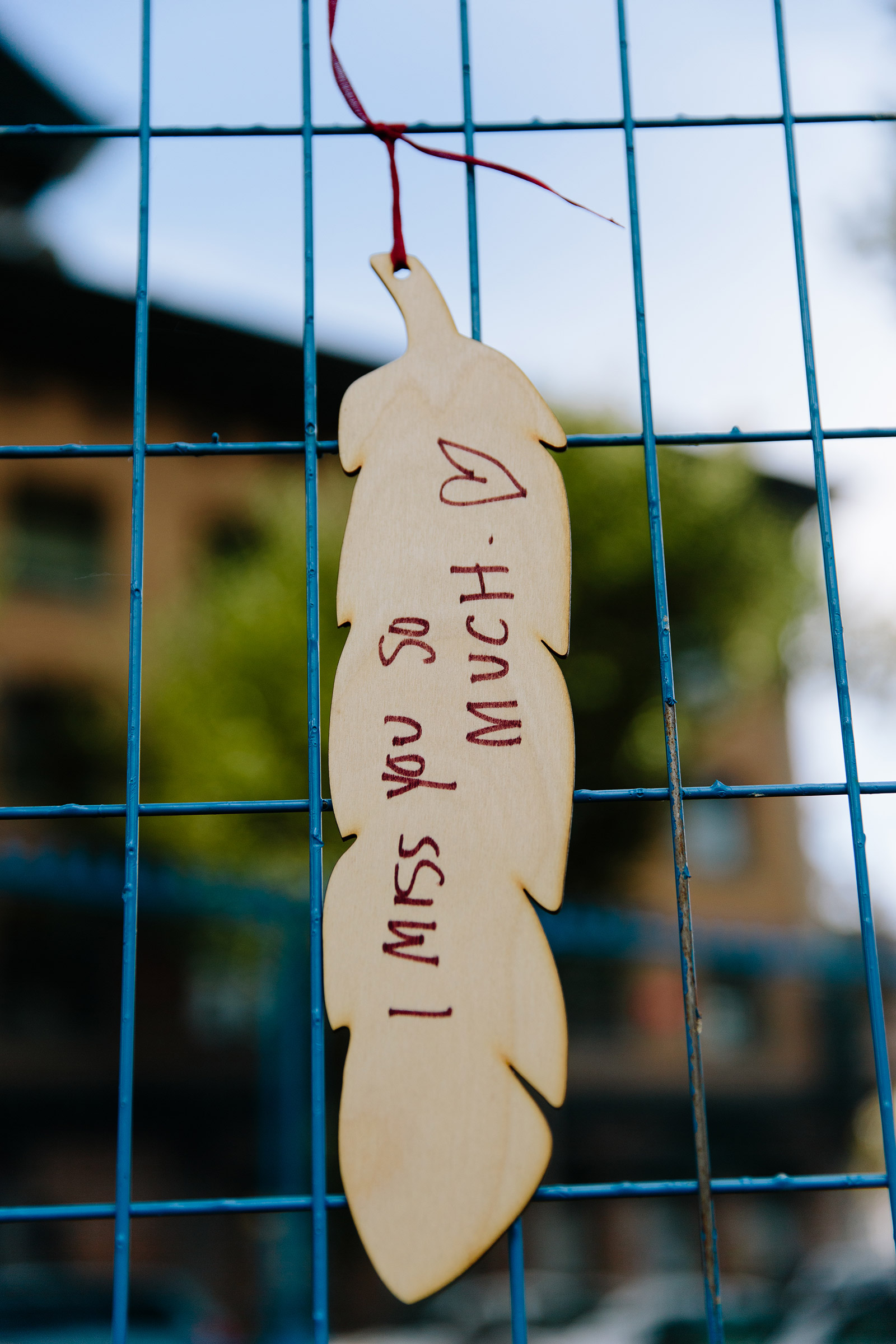

We're just sick of it. We're sick of our friends dying.

Then, after 15 minutes of slides and stats, Kalicum and DULF co founder Eris Nyx makes their pitch: they want these mothers, from a group called Moms Stop the Harm, to join them and other activists in their distribution mission, an admittedly risky protest that could land them in jail.

It’s a tough sell, but it’s critical to saving lives, say Kalicum and supporters of the “safe supply” effort.

“I’m not a criminal, and obviously, Moms Stop the Harm aren’t criminals,” Kalicum says. “We’re just sick of it. We’re sick of our friends dying.”

Everyone on the call can relate. Each has lost someone to the opioid crisis, which has soared in North America during the pandemic, especially in Canada. In the U.S., deaths rose nearly 30 percent in 2020 to a record 93,000. In Canada, deaths soared 89% over the previous year.

Behind the numbers lies a cruel irony that every parent listening to Kalicum understands, and that drives the “safe supply” movement: Opioids were perfectly legal when their children were becoming addicted to them, promoted by pharmaceutical giants and doled out by physicians who enabled the crisis by accepting drug companies’ claims they were safe.

When the reality became clear, and prescriptions became hard to come by, it was too late. Untold thousands of pain-addled patients had become hooked on what opioids provided, as had many young people who’d begun experimenting with the pills recreationally. They found relief on the streets in the form of heroin, then began dying from illicit drugs either laced with fentanyl or entirely replaced with the compound, which is 50 times more potent than heroin.

A Deadly Arc

That is the arc of the Opioid Crisis: From patient to criminal to, more and more often, early death.

The “safe supply” movement seeks to counter this deadly progression by ensuring the integrity of the dosages that users have been conditioned to crave while providing care that keeps them alive and could wean them off drugs. “It’s not who we are to stand passively by,” says Kalicum. “We’re gonna do something, and we’re willing to take on personal risks to do that. But we can look at ourselves in the mirror and know that we’re doing what’s right.”

Even in Vancouver, a city with a progressive history on the issue of drugs, “doing what’s right” means butting up against an opposing force that still views drugs as a moral failing rather than a medical problem, and that opposes safe distributions. Slowly, though, DULF and the Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users, or VANDU, are drawing attention to their effort and, on this video call winning support. At least two of the moms listening to Kalicum volunteered to distribute drugs on International Overdose Day, Aug. 31, despite the risk of arrest.

“If we lose some members, that’s okay,” says Leslie McBain, a founding member of Moms Stop The Harm. Her son died in 2014 just as lawsuits against opioid maker Purdue Pharma were first ramping up, and many were still naive to the dangers of opioids. “He had an injury on a construction site when he was 23, and the doctor just prescribed loads and loads of oxycodone,” she says of her son. “And that was his demise.”

Read more: Inside the Worst Opioid Addiction Crisis in U.S. History

In the past six years, McBain’s organization has grown to nearly 3,000 members across Canada. Their goal, she says, is to lessen the stigma of addiction and advocate for changes in drug policy in a way that “actually supports the lives of people who use drugs rather than punishes them.”

In 2003, North America’s first sanctioned, supervised safe injection site, Insite, opened in Vancouver after receiving a federal exemption to protect it from the country’s drug laws. Canada now has 37 such sites, with zero overdose deaths at these supervised locations.

In the U.S., cities with large communities of drug users like Boston, Seattle, San Francisco, and New York have tried to open safe injection sites, but none has done so legally. As a result, organizations working to help the most volatile drug users often operate in the shadows without official local or federal support.

History has shown that moving these initiatives forward often takes some form of civil disobedience from community groups.

Kalicum and Nyx are familiar with the pitfalls of trying to operate under the radar, having spent years on the front lines of the drug scourge. And as the pandemic’s effect on drug use has become clearer, with fentanyl showing up not just in heroin now but in cocaine and methamphetamine, the pair have become bolder in their efforts. They staged their first protest demanding a “safe supply” of drugs in 2020. In April 2021, they distributed “safe” heroin they tested for the first time in downtown Vancouver. Three months later, they distributed drugs in front of police department headquarters.

‘Maybe this is a good idea’

“History has shown that moving these initiatives forward often takes some form of civil disobedience from community groups,” says Kalicum. The first overdose prevention sites were set up illegally along with needle exchanges. “It took people giving needles out themselves before the government thought maybe this is a good idea,” he says.

The duo is a study in contrasts. Nyx, 30, is a witty, trans woman covered in tattoos, while Kalicum is more straight-laced, subdued, and serious. “I look like a criminal,” jokes Nyx. “Jeremy looks like he could be your best friend’s son.”

The thing about drugs is most people use them at least at some point.

But both bring a history of experience with drugs to their activism. Nyx is originally from the suburbs of Toronto. The organizing director of the Tenant Overdose Response Organizers and executive director of the Coalition of Peers Dismantling the Drug War; she says she’s used drugs since the age of 12 or 13, is estranged from her family for being queer and trans, and in turn experienced housing instability.

In 2019, after being laid off from the British Columbia Center for Disease Control, Nyx was hired to organize a conference on “safe supply.” She and Kalicum met in person for the first time at that conference after weeks of planning calls, bonded over their shared mission, and created DULF.

Kalicum was raised by a single mother on assistance in the port city of Nanaimo, where he says his family was in “great need,” and he fell into drugs and petty crime at a young age. Eventually, a local charity put him through school in a suburb of Chicago until he moved back to Canada to complete his bachelor’s degree in chemistry and biology.

Read more: A Community In Crisis

His experience with that charity helped steer Kalicum into his current activism, which includes buying drugs on the dark web and testing them for evidence of fentanyl before they’re distributed as part of the “safe supply” movement. “That organization met people where they’re at and worked to improve their lives without any expectation of return,” he says. “And that’s what I strive to put forward into the world.”

Much of DULF’s work focuses on “harm reduction,” which historically involves providing clean needles to prevent the spread of infection and disease, along with antiseptics, condoms, and anything else that might help safeguard drug users. It’s been shown to improve health outcomes that often lead to recovery. Long-term studies in Vancouver have shown that drug users were more likely to enter a detox program and save taxpayers money.

In the early ‘90s, when Switzerland was dealing with a growing heroin epidemic, it began making methadone available. It launched a heroin prescription program for some users in an effort to curb overdose deaths, HIV infections, and public drug use. As these programs have grown, the rate of new heroin users has declined along with overdose deaths, HIV rates, and crime. Other countries, including the Netherlands, Denmark, Germany, the United Kingdom, and Canada, launched similar programs.

Kalicum’s return to Nainaimo in 2016 coincided with the declaration of the opioid crisis as a public health emergency. He was shocked by the number of deaths in his home city and got in touch with a city councilor advocating for supervised drug consumption sites. Kalicum worked to set one up in Nanaimo, on Vancouver Island, and remembers, “that’s when I learned the value of direct action.”

After moving across the strait to Vancouver in 2019, he became involved with the BC-Yukon Association of Drug War Survivors, an agency that advocates on behalf of drug users, and fell under the mentorship of Ann Livingston, considered a pioneer in harm reduction. Kalicum began to see it as his “moral imperative” to work around the legal system to save lives. Around that time, he also learned of “compassion clubs,” first used by terminally ill people to access cannabis for pain before it was legal. These clubs now provide drug users with a safe supply of drugs and with spaces in which people can supervise one another while using them.

His arrival in Vancouver, as drug deaths were soaring, shook Kalicum. “Before I came to Vancouver, I’d never seen a dead body before,” he says. “And that summer, I’d seen several.” Currently almost six people die each day in British Columbia, according to the B.C. Coroners Service. Nyx says she responds to at least an overdose a week. “That f–ks a person up and creates an incredible amount of PTSD,” she says.

Nyx and Kalicum know that they can’t wipe out drug use, but neither do they see that as something that should be done. “The thing about drugs is most people use them at least at some point,” Nyx says, citing coffee, cigarettes, alcohol, marijuana and prescription meds. Most people, she notes, use these substances and are not out of control or in what is often called “chaotic” use. “I don’t want to die. I’m a perfectly functional member of society, and most people who use drugs are,” she says.

Read more: A Mother on the Pain of Losing Her Son to Opioids

What would make more sense than focusing on the minority of out-of-control, self-destructive addicts, Nyx argues, is to regulate the drug market in a way that ensures all users have the safest options possible.

Outlawing alcohol provides an instructive example. The Prohibition Era lasted only from 1920-23, but in that time the crime of drinking was driven underground into speakeasies and basements. Booze was mixed in buckets and bathtubs, and there were no labels on bottles. People had no idea what proof the liquor they were drinking was, and that was dangerous.

Today’s illegal drug markets operate in the same way. No one has any idea what they’re buying on the street in unmarked bags. “Regulation will save people’s lives,” Nyx says.

With that in mind, DULF has set out to do with street drugs what’s now common for alcohol and cigarette manufacturers: test ingredients and put clear labels on everything. The “DULF Fulfillment Center and Compassion Club model” acts as a market and consumer protection agency where street drugs are tested and distributed in packaging that states the drugs’ contents.

Nyx, designs the labels, and together they promote the mission and crowdsource money to buy illegal drugs, then test them and distribute them at protests to people who are part of already existing drug-user groups. “The free drugs go to the people in the most need,” says Nyx.

The Dark Web

Kalicum describes the system of buying drugs on the dark web, which is remarkably similar to buying just about anything else. “There are sites which are kind of analogous to eBay,” he says, where people can buy, and people can leave reviews for vendors.

“These sites will hold your money in escrow until you get your product. When you get it, you test it. You can either release the funds or create a dispute,” he says. In the case of a dispute, the website appoints a mediator to settle things.

DULF has received fentanyl instead of heroin and has been refunded thousands of dollars after creating a dispute. Still, there are unknowns, which has been one of the major criticisms of DULF: The seller might be a criminal organization, for instance. But Kalicum says the current state of drug legislation has left people serious about quality control no choice. “It’s not what we want to do,” says Kalicum, “but we’re forced to leverage the resources that we have access to, and that’s the dark web.”

They pay for the drugs with a private cryptocurrency called Monero that claims to be untraceable.

Kalicum was one of the first people hired to begin testing street drugs while working as a technician with the British Columbia Center on Substance Use, where he learned a technology called FTIR spectroscopy. The technology uses infrared light to tell him what’s in a substance and in what quantity. His goal eventually is to be able to use mass spectrometry, which shows a more refined level of detail.

Nyx keeps track of the data on the drugs they distribute. Each person receiving a dose is asked to answer three simple questions on a form: did you use the drugs yourself, did the person using the drugs overdose, and will you score the drugs on a scale of 1 to 5? So far, Nyx says, of the 907 forms filled out, none of the users has overdosed. In this early phase, they don’t think that data can be leveraged in any official capacity, but Kalicum says, “it might act as a kind of carrot for researchers to do something substantial.”

Kalicum would like to see heroin and other drugs provided by the government or a regulated supplier, the way methadone is now, and not by the illicit markets. “You’d be taking money out of the hands of organized crime,” says Kalicum. “People can get their drugs there, use them, and it acts as a portal to health and social services.”

In May 2021, Vancouver offered up its own solution to the drug issue: the Vancouver Model, which would decriminalize simple possession of all drugs up to a specific amount. It recognizes substance use and the overdose crisis as a public health issue, not a criminal justice issue. Even so, DULF and many activists feel the proposal fails to address the sourcing of toxic drugs as the main cause of fatalities and that the amounts individuals would be permitted to possess don’t conform to actual patterns of substance use.

Vancouver’s Police Inspector, Phil Heard, who took a leading role in proposing the plan, acknowledges the criticism but says it’s up to scientists, not cops, to study its impacts, assuming the idea is implemented.

In the meantime, DULF is pushing hard to get permission to implement its own plan. In August, it submitted a 19-page letter to Canadian health officials asking for an exemption to practice its “safe supply” model. “We are saying this is a health emergency,” says Kalicum. DULF isn’t alone in what some consider radical approaches to the drug issue. As the pandemic raged through Canada in 2020, Canadian Health Minister Patty Hajdu, seeing the impact on drug users, raised the idea of injectable pharmaceutical-grade heroin, among other possible solutions.

Signs of progress

In August, Nyx and Kalicum presented their model to Inspector Heard and Staff Sergeant Jason Chan. The Aug. 31 protest marking International Overdose Awareness Day went smoothly, and none of the moms who took part was arrested. DULF has also received a “letter of support” for its testing and safe supply plan from Vancouver Coastal Health, a regional health authority with a budget of more than $3 billion dollars. Several Canadian policy experts, have also signed on, including many from the B.C. Centre on Substance Use and the Canadian Drug Policy Coalition.

And on Oct. 7, the Vancouver City Council voted to support DULF’s plan, though it only passed after an amendment to ensure that drugs would be purchased through legal means. That would require activist groups to work with companies like Fair Price Pharma to supply, test, and package legally sourced drugs before dispensing them to members of a compassion club.

Kalicum and Nyx addressed the meeting and urged officials to act quickly. then sort out the details of where to find drugs. “What we’re saying is a temporary stopgap. But stop the deaths first, then figure everything out after,” Nyx said.

Everyone witnessing the overdose epidemic agrees that it is only getting worse. Heard, the police inspector says 2020 was a “record year,” but “2021, it’s looking to be even more deadly.” Sure enough, the day after the City Council hearing, Nyx witnessed yet another drug death, this time of an 18-year-old.

Even with growing support, she and Kalicum are exhausted. They’ll need to apply for grants to fund their effort. “We have a colossal amount of work to do,” she says wearily. “People are constantly dying, and there is no end in sight.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com