Four years ago, the stories of a young man named Billy with his mother Kristina and stepfather John Barboza appeared in The Opioid Diaries, a special issue of TIME calling attention to the dire rise in accidental overdoses caused by the opioid epidemic. Last year more than 87,000 Americans died of drug overdoses over the 12-month period that ended in September, according to preliminary data from the CDC, the highest yet, and the toll continues to rise. Billy died on April 9, a month to the day before Mother’s Day.

“I’ve been shooting heroin for sixteen years. I’m 31 now,” Billy said during our first interview in January 2018 when he was living on the bitter cold streets of Boston. “My father died of an overdose when I was a kid.

“My mother came out here yesterday to see me, and we went to eat. I don’t like to bring it around my mother. So I stay away from home whenever I’m actively using. She’s been wanting to reestablish a relationship with me regardless of what’s going on. I’ve been allowing her to do that.

“I just – I don’t want her to get hurt, you know what I mean. My mother’s been through a lot.”

At the end of the conversation, I asked if I could call her, and he said, “Yeah, she’ll definitely talk to you.”

On her couch in Wareham, Massachusetts, Kristina’s opened up about her son’s struggle with drugs, then kept the conversation going for years, after Billy’s life became public in the news, then afterwards as an advocate for him. What follows is Kristina Barboza, in her own words, gathered from interviews, phone calls, and text messages over the last four years.

January 2018, interview at home, Wareham, Massachusetts

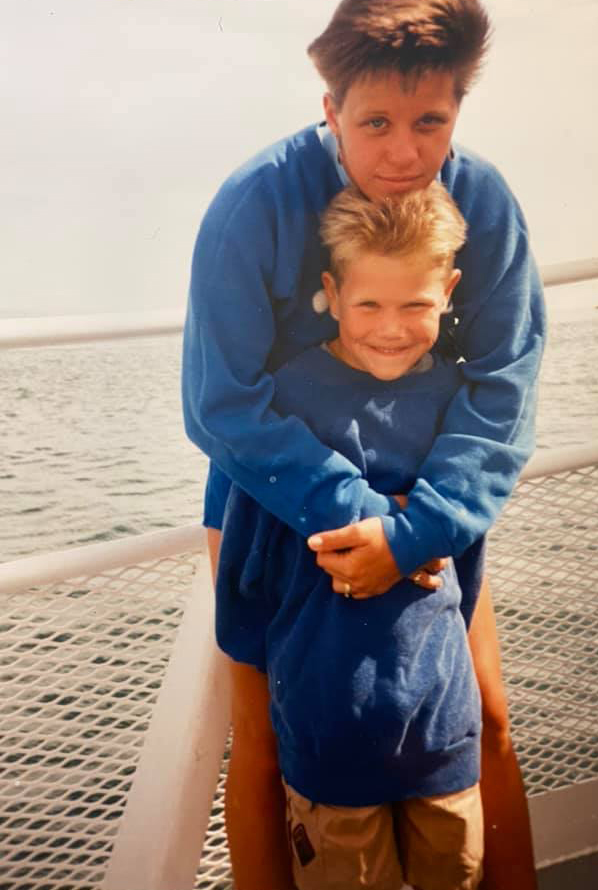

“Billy started using substances at a young age. He was probably around 12, 13, when he started dabbling in smoking pot, drinking alcohol. Then he started with opiates. As a parent, you don’t learn about these things a lot of times until after they’ve happened. He was in and out of treatments, in and out of jail. He quit high school when he was about 16.”

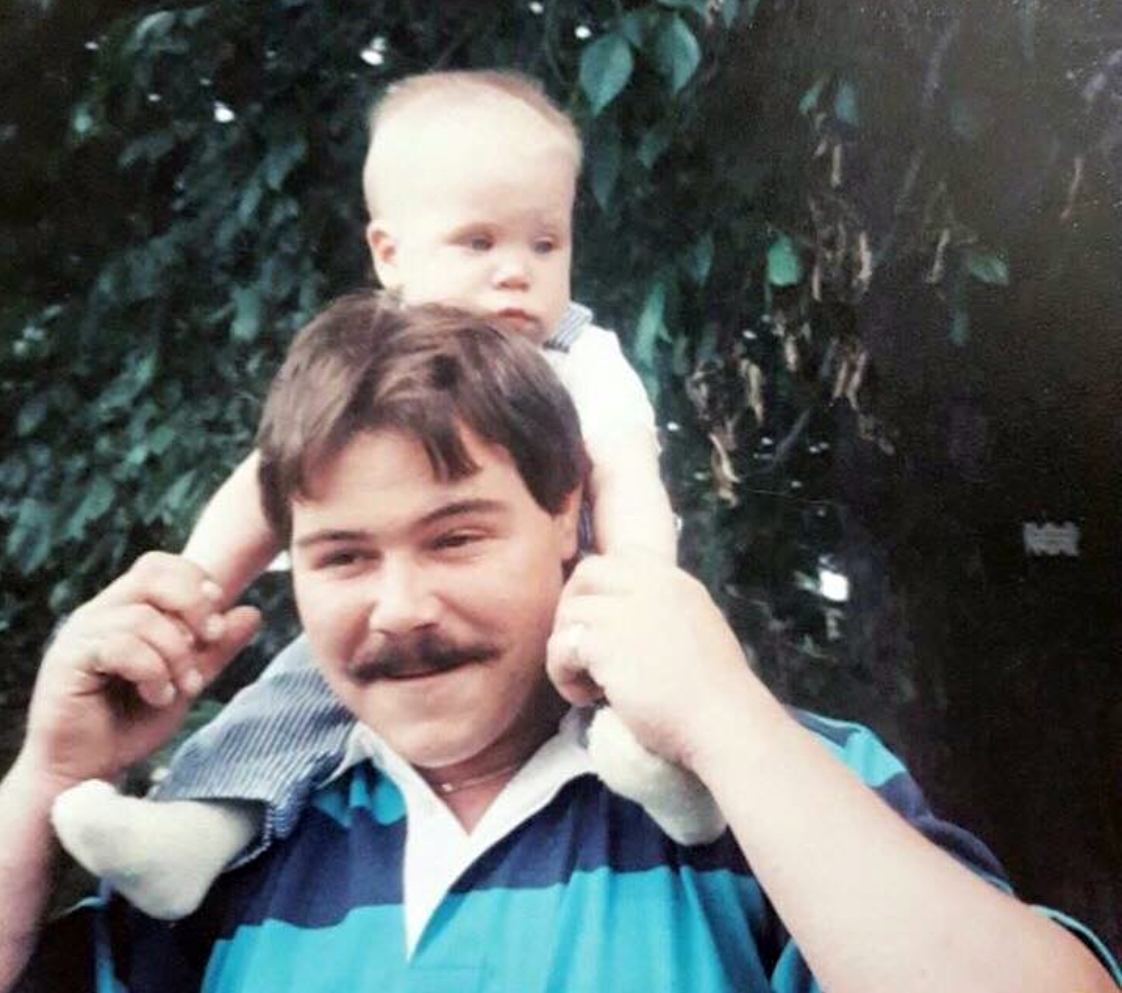

“Billy was 3 when his father died. I think that played a big part for him in self-medicating, trying to numb out the pain.

“As a kid looking for an identity, he was aware that his father had died from a drug overdose. Still, Billy just took off with drugs, alcohol, and getting into trouble. He was in and out of treatments, in and out of jail.

“Billy’s energy was hard to contain. He ended up leaving school at 16. He’s very intelligent. ‘I didn’t even study for the GED test,’ he said, ‘I just took it, and I passed,’ he told me. He’s also very artistic. His passion is to become a tattoo artist. I have one he gave me on my foot of some mountain peaks. He made the tattoo when he was living here, the summer before.

“You have to remember that this has been going on for like a long time with Billy. I’m sitting here, and I’m thinking back to how many treatment facilities he’s gone through, how many times he’s gone to jail. It’s layers and — upon layers upon layers.

“When I saw him this past Saturday, and I looked at his hands, they were so swollen. I noticed the discoloration. I came home, and I just sat on the couch all day.

“Since Billy’s been in Boston, I think I’ve gone in from Wareham three or four times to see him. I went in with my stepmother, and we took the train. We saw him walking over, and his hair was grown out and wild, and he had like these wild eyes. I knew he was under the influence of something.

“I remember I had these mixed feelings, so happy to see my son but so shocked at the transformation that had taken place. We spent the day walking through Boston, getting him something to eat. When we had to leave, that was the hardest thing I had to do. Giving him a hug and leaving and not knowing if I would see him again.

“Two years ago, he wanted to get help. He went into detox. He was doing wonderful for about three months. He started seeing his 4-year-old son. He was working, he was clean, he was healthy. I mean, we really both thought that this was it, and he wound up relapsing.

In 2017 Billy appeared on CNN using intravenous drugs on TV, and suddenly, his drug use became very public. When the world knew that, I felt I had to make a stand. I decided to reach out to CNN via Twitter and posted pictures of him saying, “Billy is my son”. I hadn’t known where he was, and at that point, I wanted to humanize him. After that, I appeared on CNN and in TIME.

“I did speak at Alanon meetings and Learning To Cope meetings about his substance abuse. I began working at Duffy Health Center for the homeless as a medical assistant three years ago, and I began to feel more comfortable talking about his homelessness.

“It hasn’t been until more recently that I’ve kind of ‘come out in terms of talking about Billy. Because for so long, I did feel isolated in it. I did feel embarrassed. People would ask me, you know, “Oh, so how many kids do you have? What are they doing now in their lives?” And it was almost like, “Ugh.” I was embarrassed.

“But more recently, I’m like, ‘Yeah, I have two children. Yes, my son is addicted. Yes, currently he’s homeless.’ I try not to say that with shame. But it’s very difficult.

“Growing up, my mother committed suicide. That was so taboo at the time. So before Billy’s addiction, I was already living with this layer of shame. My mother didn’t love me enough? You know what I mean? This is crazy when you think about it, but that’s what this kind of stuff does to your psyche.

“I don’t give up hope. The fact that Billy’s still breathing, the fact that he’s still alive, means there is hope.

“There have been times when I have gotten so caught up in my head by fear or anxiety. Is today going to be the day that I’m going to get the call that he’s overdosed? Because that is a reality for so many.”

Over the years, the conversation continued over text and phone calls. Kristina’s updates on Billy’s life covered jail, rehab, returning to the streets. Her worries were constant.

On April 8, 2021 an update arrived by text

“I’m letting you know of what has happened to Billy since our last conversation. Billy has been in Medical ICU at Tufts in Boston since last Thursday. He had a heart attack. He’s been sedated and intubated since. He has numerous complications, and we will be taking him off of life support today. Please keep him in your thoughts and prayers as he transitions from this life. Thank you for shedding a light in this epidemic and for being a friend to Billy and I.”

The next day she wrote: “Billy passed away at 5:10 pm. Myself, his sister, and Aunt were all by his side. He went peacefully”

“I was always so worried Billy would die alone on the streets. I’m grateful we were able to be with him, and he is now at peace.”

Four days later, Barboza appeared on CNN, talking to Anderson Cooper from her living room.

“I’m in the midst of facing my biggest fear. He has died,” she said. “You can’t save anyone. You can try to help, you can try to be a catalyst, you can love. Believe me, if I could have saved Billy, I would have saved Billy.”

A few days later , we spoke by phone.

“As I sit here and think back to where my pain began, I think back to the death of my mother. I remember as a young person how I wanted to talk about it and was shut down. I began early to numb that trauma with alcohol.

“I was in Alateen by thirteen, and I met Barry when I was eighteen. He was my first sober love, and I always felt safe with him. He was this big teddy bearish kind of guy and a lot like Billy. He was always there for the underdog.

“We were two young people in AA, but we had our own baggage, and we hadn’t really unpacked all our stuff. I was twenty-one when I had Billy. Very young.

“I didn’t have a role model as to how to be a mother. I got postpartum, and Barry started picking up drugs and using again.

“My first real attempt to stop the cycle was when I said I’m taking Billy and leaving. Barry made a few attempts to turn his life around, but he just couldn’t do it. He died at 29 in a garbage-strewn, cockroach-infested apartment from the disease of addiction. I just remember thinking, how am I going to raise this son?

“I wanted to do something different with Billy’s loss than I did with my own mother. So I had gotten Billy into counseling. I think Billy had a hard time, and I don’t think he ever fully embraced that loss.

“Now that Billy’s father died and Billy, I pray his son does not have the gene. I just want the cycle to stop. It’s in my family, and I found recovery. So I’m really hoping that this is the end of that line.

“I’m now part of this Facebook group for mothers who have lost children to substance abuse. I never wanted to belong to that club, but now I do. I met another mother who said she saw me on CNN and in TIME, and she said I gave her the ability to write her son’s obituary honestly, lose the shame and have the courage to say that this was my son and he had an addiction.

“I think we need to get rid of the stigma and judgment that alienates us. If we can’t communicate, we can’t solve it.

“We are taught that we’re supposed to give everything as parents. We are supposed to keep them safe and nurture them. We’re supposed to kiss away the hurt, but all those rules don’t apply when it comes to addiction.

“I was starting to lose it at one point. I remember the lengths that I would go to keep Billy safe. I would hear all these mixed messages at support groups that I need to let go. You don’t want to enable them. I started to realize that in order to function, work, love, give, I had to draw boundaries.

“There were times when I would go wire him money, and I would kick myself saying what did I do?

“I was just trying to love my son.

“The last time I spoke to Billy, and he called me and sounded really upbeat, saying he was staying at a shelter and taking antibiotics, and then at the end, he asked me to send him twenty dollars. I said no, I can’t. And he ranted, “oh, you’re not going to help?” and that was our last conversation.

“What would that last twenty dollars have done? I don’t know? It was a huge struggle for me.

“The thing that was the hardest for me with Billy was the homelessness piece. I thought maybe people were judging me. I knew the only way I would have a relationship with Billy was to meet him where he was at. I mean that geographically, emotionally, mentally. He couldn’t reach any of the bars I put up for him, and I didn’t want to not have a relationship with my son.

“And I know words matter. We’re not one single thing.

“Words matter. Let’s not call someone a drug addict. They suffer from substance abuse disorder.

“We’re made up of so many different pieces, and with Billy, he was funny, he was a tattoo artist, he was a dad, he was a son, a brother, and he also suffered from substance abuse disorder. So words matter in taking away shame, stigma and making it all sound dirty.

“Even in saying someone is homeless, they are not even that. It’s something that’s happening in their life. It’s a situation that they’re in, but they’re not it. Once we start stamping people with these labels, it doesn’t give them any room to change. How are we ever going to show them all these other things that they are?

“I still say, don’t give up hope. Love them, get rid of the stigma. They’re people like you and I but and stuck in that cycle.

“I’m all for safe injection sites and all forms of harm reduction. We can’t just be like, out of sight, out of mind. To understand it, we have to look it in the eyes. You have to lean in and not away. We are in this all together.

“He’s here, and I know he loved me.”

Kristina posted her son obituary on Facebook April 11

William (Billy) Andrew Donovan, born September 19, 1986, in Stoughton, Massachusetts, passed peacefully on April 9, 2021 at Tufts Medical Center in Boston. Present with him for his final breath were his mother Kristina, sister Rebecca, and Aunt Martha.

Billy’s biological family would also like to acknowledge the numerous members of Billy’s chosen family from Mass Ave as well as the various service organizations who reached out to him over the years, as well as the compassionate and professional nursing staff and doctors from Tufts Medical Center. You are all so greatly loved and appreciated.

Billy was a carefree, magnetic, and exuberant personality with a gentle and compassionate heart, who much like his father Barry, never met a stranger and was quick to come to the aid of anyone in need, giving of whatever meager resources he had, his time, attention, and affection. Because of his struggle with heroin addiction, he was influential in many people getting clean. Billy displayed talent in drawing and as a tattoo artist. He was an immensely resourceful young man who left a deep impression in the hearts and minds of all who were fortunate to have met, known, and loved him. He is deeply missed by all.

In lieu of flowers, donations can be made to the Boston Healthcare for the Homeless Program.

If you or someone you know needs help, please contact the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration at 1-800-662-HELP or findtreatment.samhsa.gov

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com