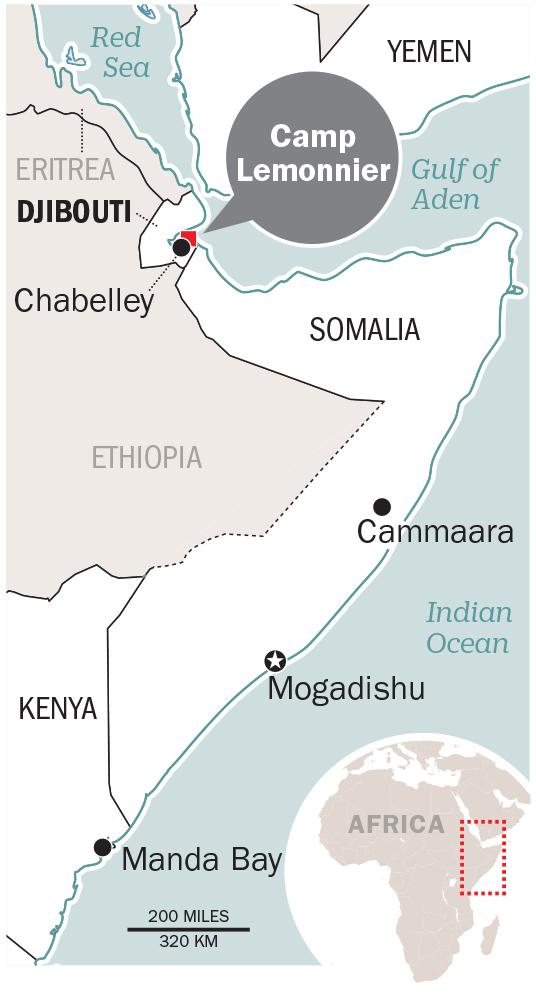

In a remote corner of eastern Africa, behind tiers of razor wire and concrete blast walls, it’s possible to get a glimpse of America’s unending war on terrorism. Camp Lemonnier, a 550-acre military base, houses U.S. special-operations teams tasked with fighting the world’s most powerful al-Qaeda affiliates. Unfolding over miles of sun-scorched desert and volcanic rock inside the tiny country of Djibouti, the base looks—the troops stationed here will tell you—like a sand-colored prison fortress.

Inside, two subcamps sit behind opaque 20-ft. fences ringed with yet more razor wire. The commando teams emerge anonymously from behind the gates and board lumbering cargo planes to fly across Djibouti’s southern border with Somalia for what they call “episodic engagements” with local forces fighting al-Shabab, al-Qaeda’s largest offshoot. General Stephen Townsend, commander of military operations in Africa, describes it as “commuting to work.” The Pentagon has dubbed the mission Operation Octave Quartz.

The operation may be a sign of things to come. Despite President Joe Biden’s pledges to end America’s “forever wars,” he doesn’t plan a retreat from global counterterrorism missions. One month after his chaotic Afghan pullout, Biden is continuing the work his predecessors began, drawing down high-profile military missions abroad while keeping heavily armed, highly engaged counterterrorism task forces in place in trouble spots. The President plans to fight terrorism from “over the horizon,” he says, parachuting in special operators, using drones and intercepted intelligence, and training partner foreign forces.

Some 1,500 miles northeast of Lemonnier, about 2,500 U.S. forces operate from bases across Iraq, where they routinely come under rocket and mortar attack. An additional 900 forces are on the ground in Syria within striking distance of ISIS and al-Qaeda. In a June 8 letter to Congress, Biden listed a dozen nations, from Niger to the Philippines, where U.S. troops were on counterterrorism operations. These missions are undertaken by 50,000 men and women on the front lines of an active, under-the-radar conflict mainly waged in the Middle East and Africa.

Just how deeply Biden should invest in what used to be called the Global War on Terror has been the subject of live debate inside the Administration. His national-security team is finishing a new counterterrorism strategy that will in turn decide how big a global deployment of forces the U.S. makes. Biden has already halted most lethal drone strikes, ordering commanders to consult the White House on decisions to strike, and has initiated a review of when such lethal force should be used. At home, he’s increased counterterrorism investigations of domestic violent extremists, which, after the Jan. 6 attempted insurrection at the Capitol, the FBI rates as the single biggest threat to the homeland today.

The evolving U.S. approach represents a turning point for America and the world. Critics of U.S. military engagement abroad say the country should stop fighting shadow wars altogether, arguing that they can never be won, and that the ensuing civilian casualties and other costs create a self-sustaining global conflict. But full withdrawal would be dangerous. The U.S. military’s leaders worry their chaotic pullout from Afghanistan, and a new, diminished approach to fighting terrorism worldwide, could endanger Americans and their allies. “A reconstituted al-Qaeda or ISIS with aspirations to attack the U.S. is a very real possibility,” the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Mark Milley, told Congress on Sept. 28. “Strategic decisions have strategic consequences.”

Biden is banking that a low-profile globe-spanning battle, and whatever collateral damage comes with it, will be politically palatable enough for Congress to keep funding, and effective enough to keep existing and emerging militant groups from threatening America. At Camp Lemonnier, the U.S. military’s only permanent base on the African continent, the approach is already being put to the test every day.

In the brightening dawn of Aug. 24, a truck loaded with goats and sheep pulled up to a Somali military camp near the central town of Cammaara. Suddenly the road erupted into a fireball. The explosion was the beginning of a multipronged al-Shabab attack that left four Somali soldiers dead and several others wounded.

As the chaos unfolded on the ground, American special operators deployed as part of Operation Octave Quartz were watching through the high-powered cameras of a drone flying overhead. The U.S. forces were sitting far from the combat in a makeshift operations center elsewhere in Somalia, where they attempted to remotely advise their Somali partners, called the Danab Brigade, via encrypted radio. With their allies under serious threat, they ordered up an airstrike on the militants’ positions.

The U.S. bombing run ultimately turned the fight in Danab’s favor. The Somalis gained back control of Cammaara, which lies on a coastal smuggling route that is valuable to al-Shabab. U.S. Africa Command (AFRICOM), which oversees all American military operations on the continent, characterized the airstrike as a “collective self-defense strike” in its public announcement, a description that allowed commanders to stay in line with the Biden Administration’s mandate that airstrikes in Somalia be approved by the White House unless they’re taken in self-defense.

Targeted drone strikes may help U.S. partners win individual battles, but they are unlikely to win a war against an entrenched enemy like al-Shabab. The group, whose name in Arabic means “the youth,” has waged an insurgency against Somalia’s fragile U.N.-backed government since 2007. Al-Shabab has received less attention than other terrorist organizations, but at 10,000 fighters it is al-Qaeda’s largest affiliate, controlling vast swaths of rural, south-central Somalia. Like the Taliban in Afghanistan, it runs a shadow government that extorts business owners and imposes its own harsh form of Shari‘a, or Islamic law, with punishments such as public flogging, stoning and amputation. The group earns as much as $15 million per month in taxes, according to an October 2020 study from the Hiraal Institute, a Somalia-based think tank, revenue on par with that of the Somali government itself.

Al-Shabab strikes in the capital of Mogadishu at will. On Sept. 25, an explosive-laden car detonated near the presidential palace, killing at least seven people. Eleven days earlier, a suicide bomber walked into a tea shop and detonated an explosive vest, killing at least 11. Al-Shabab is responsible for the deaths of more than 4,400 civilians since 2010, according to the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project.

The group has occasionally carried out high-profile attacks beyond Somalia, including the assault on Kenya’s upscale Westgate shopping mall in 2013 that killed 67. The militants also launched the January 2020 attack on a Kenyan military base in Manda Bay, where U.S. troops were training local forces. An American soldier, Specialist Henry Mayfield Jr., and two U.S. civilian contractors were killed.

For years, the U.S. has been satisfied with containing al-Shabab. But the Taliban’s conquest in Kabul has stoked new fears that something similar may befall the frail government of Somalia. Al-Shabab has praised the takeover of Afghanistan on social media channels and repeated its desire to strike America and its allies. Unlike with the Taliban, whose sheltering of al-Qaeda paved the way for 9/11, it’s unclear what kind of damage an al-Shabab takeover could inflict on the U.S. A Pentagon inspector general report from November noted the group’s threats to kidnap or kill Americans in neighboring Kenya. “Al-Shabab retains freedom of movement in many parts of southern Somalia and has demonstrated an ability and intent to attack outside of the country, including targeting U.S. interests,” the report said.

The efforts to help stabilize Somalia have had some successes, like when Kenyan troops as part of the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) drove al-Shabab out of Mogadishu and the port town of Kismayo in 2011. But AMISOM has been unsuccessfully trying to hand over the fight to the Somali government ever since. “We know we cannot stay forever, but we do not want to see all the gains reversed,” says Kenyan Lieut. Colonel Irene Machangoh. “They can strike at any time.” The fractious Somali government, plagued by corruption and complacency, depends on foreign funding and training to support its military, and “Al-Shabab is not degraded to the point where Somali security forces can contain its threat independently,” the inspector general report found.

The U.S. has a checkered history of deployments to Somalia. It mostly pulled out after the infamous “Black Hawk Down” incident in 1993, when 18 American soldiers were killed and two helicopters were shot down over Mogadishu. After 9/11, contingents of U.S. special-ops forces started to rotate through the anarchic nation. Those missions targeting al-Shabab continued for years until President Donald Trump’s final days in office. Citing his own desire to end America’s “forever wars,” Trump ordered a full withdrawal from Somalia by Jan. 15, 2021, days before Biden was sworn in.

The U.S. had Camp Lemonnier nearby to which it could withdraw many of its forces. The Marines had first come to the base, a former French Foreign Legion garrison, in 2002 because of its strategic location. Near the choke point where the Red Sea meets the Gulf of Aden, it is on a sea-lane that’s critical to commercial shipping, but also to ensuring military supplies reach the Persian Gulf. Djibouti, a French colony until independence in 1977, is a politically stable nation that was willing to lease the U.S. a scrap of land sandwiched between an airport and a harbor.

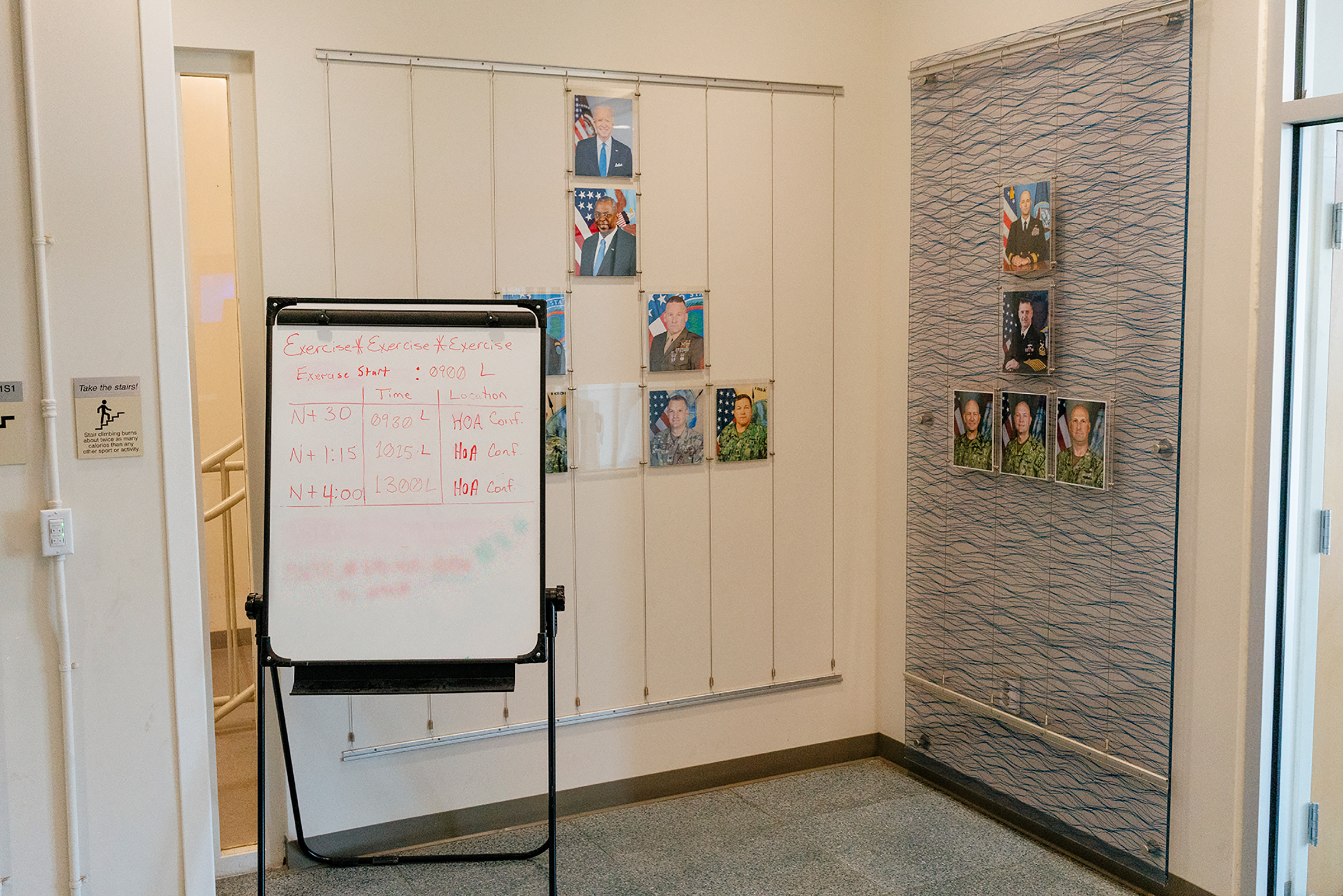

From the start, the base served as a launching pad for U.S. operations against al-Qaeda in the region. Now, it’s at the forefront of Biden’s “over the horizon” approach. At nearby Chabelley airfield, drones take off on missions bound for Yemen, where they fight al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), or for Somalia, just 10 miles south. The official name of the mission is Combined Joint Task Force–Horn of Africa—but the military, in its passion for acronyms, calls it CJTF-HOA. “We don’t want to own all the problems in the region, but we do want to be part of the solution,” the task force’s commander, Major General William Zana, tells TIME. “The U.S. presence in the region is a modest insurance policy to help achieve greater stability in the Horn.”

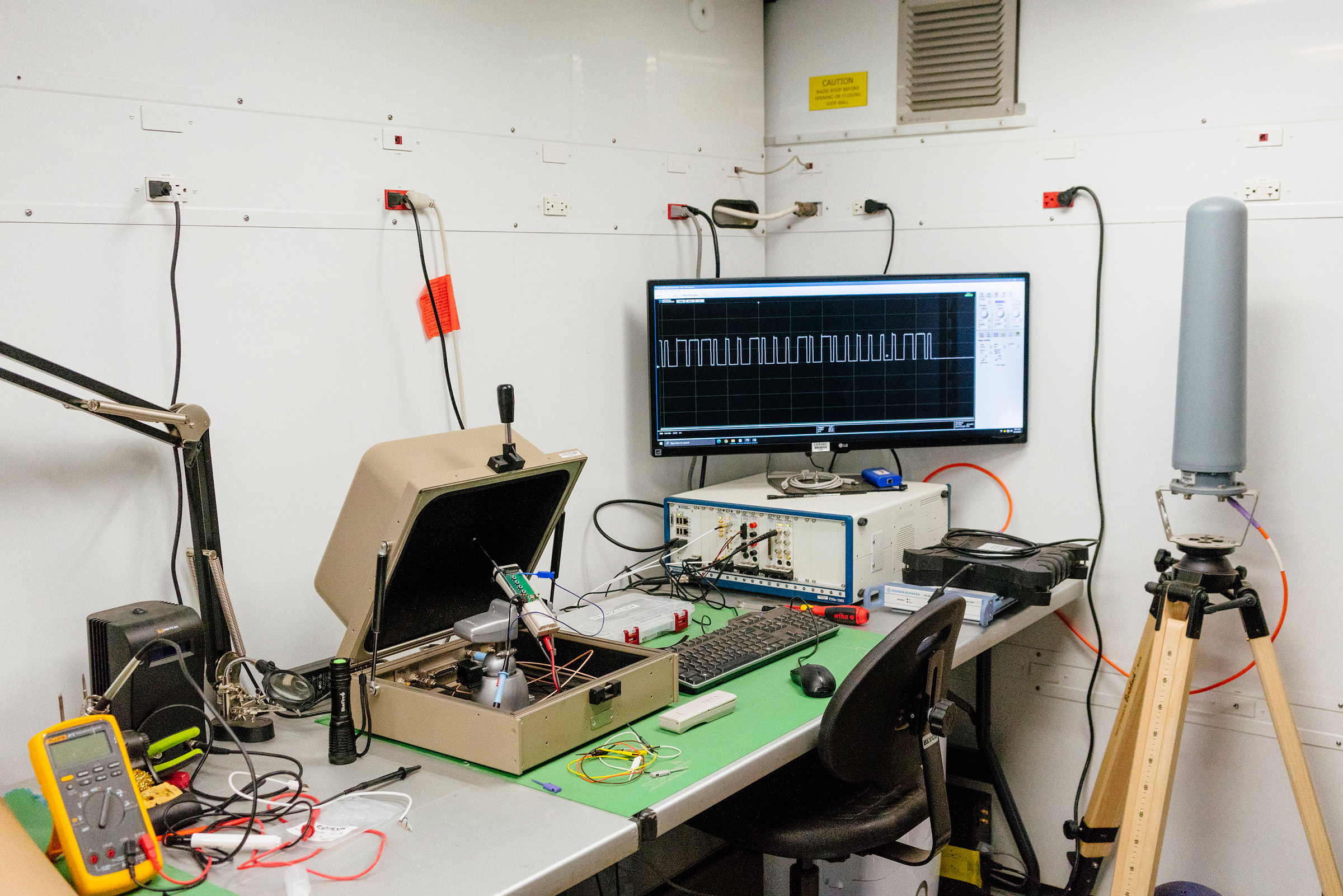

The deployment at Lemonnier may be modest, but it’s effective. What began as an 88-acre Marine Corps outpost is now a vast combat hub, home to around 5,000 U.S. troops, civilians and contractors who train regional militaries, collect intelligence and deploy to combat zones. The command building bristles with antennas and satellite dishes, while an on-site forensics lab helps specialists hack into suspected terrorists’ phones and laptops, feeding future missions across the continent. The war these troops are fighting doesn’t turn on breaking the enemies’ defensive lines or sacking their seat of power. They grind along, ensuring an amorphous threat doesn’t grow into something more.

Commuting to Somalia, though difficult, may serve as a model for fighting terrorist groups from the distance Biden wants. Already, this mission is similar to the one the U.S. now carries out in Afghanistan and other nations: developing intelligence on suspected terrorist activity, largely from airborne surveillance, captured communications chatter and images captured by drones circling overhead, then launching strikes.

But it has its own costs. During the Trump Administration, the U.S. military was handed more authority to target al-Shabab leaders, bomb-makers and operatives. There were 203 U.S. airstrikes on Somalia during Trump’s tenure, far more than were carried out under George W. Bush or Barack Obama. Trump’s willingness to use airpower led to rising claims of civilian casualties. Airwars, a London-based nonprofit, has received more than 100 allegations that innocent Somalis were killed under Trump. Those deaths are a big reason Biden launched a review into counter-terrorism policy, officials say. So far, only four strikes have been carried out under Biden, all in self-defense, according to the military. But with fewer troops on the ground, the U.S. military will likely become increasingly dependent on airpower in helping the Danab, Somalia’s special forces.

It’s not clear that remote war will work. Lawmakers, terrorism analysts and current and former government officials say that no technology can substitute for troops on the ground. Troops can’t develop strong personal relationships or understand local dynamics from afar. “We can remotely advise anybody,” one U.S. official says, “but it’s just more efficient when you’re there one-on-one.”

The U.S. military is prepared to continue the Somalia mission from afar, though it prefers to operate alongside its Somali partner force, the Danab. “The reposition of forces outside Somalia has introduced new layers of complexity and risk,” AFRICOM commander Townsend told U.S. lawmakers in April. “Our understanding of what’s happening in Somalia is less now than it was when we were there.”

Humanitarian groups, for their part, have repeatedly alleged that “over the horizon” strikes have killed or injured civilians in AFRICOM’s area of operations, as they have in other parts of the world where unmanned drones launch attacks. The true toll of civilian deaths is significantly higher than the handful AFRICOM has admitted, says Chris Woods, director of Airwars. “U.S. military commands so routinely ignore reports of tragedies from affected communities,” he says. U.S. Africa Command says it researches each allegation it receives and refines tactics to avoid civilian deaths.

Biden’s critics, like Human Rights Watch, say his strategy will result in a never-ending battle, and point to the Afghan army’s spectacular collapse after 20 years of funding and training as evidence his approach is flawed. The U.S. military argues that by training local forces and joining them on operations, the U.S. can keep an eye on the evolving militant threat, and justify airstrikes if partner forces come under fire—a kind of trip wire for targeting terrorists.

About 10 miles off base from Camp Lemonnier, the U.S. Army’s 2nd Security Force Assistance Brigade trains a group of recruits from a Djiboutian infantry unit, which may one day join the AMISOM mission. Marksmanship training takes place on a windy Saturday at the foot of Mount Gubad. The young men lay on their bellies in dirt the color of dried blood, firing their M4 rifles at paper targets roughly 50 yards away. The snap of gunfire resounds for miles. Sergeant First Class Jonathan Mills, 41, paces back and forth behind a dozen of the soldiers. “Hold your lead hand tight, and keep your eyes on the target,” Mills shouts, before an interpreter translates into French.

Aside from a 2014 attack that killed two at the La Chaumière restaurant in Djibouti City, the country hasn’t suffered much from al-Shabab’s violent campaigns. The nation has, however, capitalized on its strategic position, hosting bases for France, the U.S. and China—Beijing’s first overseas military facility. The bases, and foreign investment in local infrastructure, ensure some economic benefit from the regional counterterrorism campaigns.

Many of the Djiboutian troops come from parts of the impoverished country where quarrels are often settled with fists, rocks or shards of glass, and some have the scars to prove it. Now they wear the high-and-tight hairstyles of their American instructors, dress in similar camouflage uniforms and fire the same weapons. While they have not fought in Somalia, their commander, Lieut. Colonel Mohamed Mahamoud Assoweh, did throughout 2016 and 2017. “The fighting was very difficult,” he says, walking among volcanic rocks the size of beach balls. “Now that [al-Shabab] see what happens in Afghanistan, maybe they think they can wait us out.” Wearing a red beret and wraparound sunglasses, Assoweh says he’s pleased with his troops’ progress. He’s also happy with his arsenal of American-made M4s, .50-caliber Browning machine guns, encrypted radio systems and 54 humvees, even if it’s nearly impossible for his men to maintain. “This is what we need to fight,” Assoweh says of the al-Shabab threat.

And so the war on terrorism continues, marking grim anniversaries year after year, despite the talk of withdrawals and homecomings. At Camp Lemonnier, on Sept. 11, 2021, hundreds of troops stood in the windless heat in commemoration of the 9/11 attacks. It wasn’t yet 9 a.m., but the temperature had already soared past 104°. Rings of sweat began to appear upon the bands of the troops’ camouflage caps.

Twenty years ago, many of these service members were toddlers. Some weren’t born. But the attacks led them to a country that few could have found on a map before they received their deployment orders. “Things changed remarkably and irreparably after the attacks,” Major General Zana tells the service members. “None of us would be here. The street, this building, the planes that flew overhead, the relationships we formed, none of this would be here.” The troops uniformly salute an American flag as it’s pulled, inch by inch, to half-staff. An Army specialist steps into the silence, wets his lips and lifts his trumpet to play the distinctive 24 notes of taps—G, G, C, G, C, E. —With reporting by Nik Popli/Washington and Simmone Shah/New York

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to W.J. Hennigan/Camp Lemmonier, Djibouti at william.hennigan@time.com