The tears that slid down her cheeks took Texas state representative Senfronia Thompson, 82, by surprise.

Maybe they were drawn by the words of Virginia state senator Jennifer McClellan, a Black Democrat who this year launched an unsuccessful bid for governor, as she described the barriers that had made it difficult and at times impossible for her parents and her grandparents to vote. Maybe by the setting, outside a library in Alexandria, Va., less than 10 miles from Capitol Hill, where, the very year Thompson was born, a group of Black residents had staged a sit-in to demand integrated access. Or maybe it was the reminder that even after her five decades in the Texas House—longer than any other woman, Black person or Democrat—the tools and tactics of Jim Crow are still functioning. Here she was in the capital region on July 16, come to beg the U.S. Congress to do something to protect voting rights.

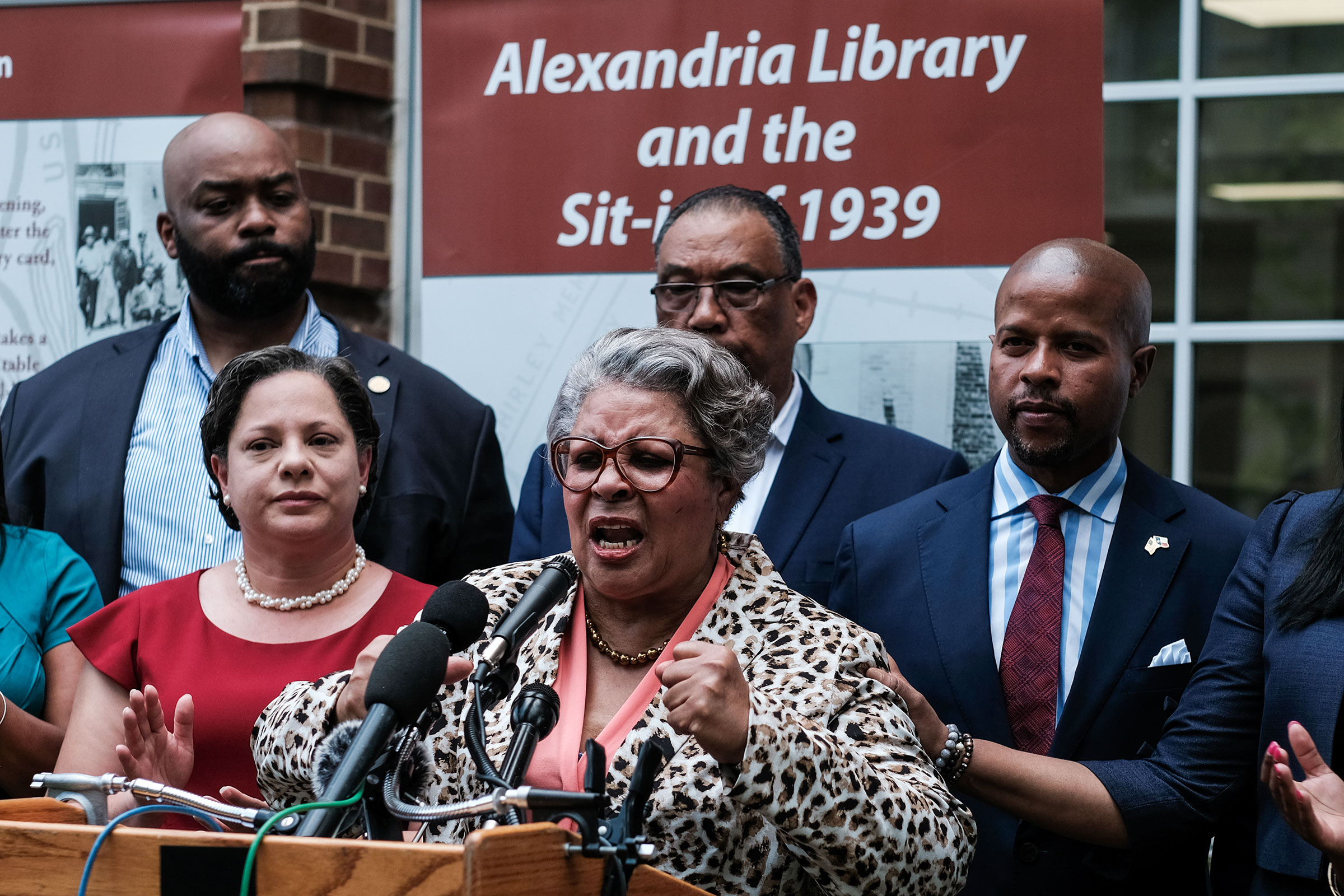

”I think about how we had to come a long ways and watch signs that say ‘No Dogs. No Negroes. No Mexicans,’” Thompson says, to a bank of TV cameras at the library. “When dogs [were un]leashed on our people. When they were beaten. When they were bombed. When they were killed and all of the things we had to endure. Haven’t we done enough?”

Thompson’s voice rises, wavers, then breaks. “Haven’t we paid the price enough? What is it going to take for us to be able to be Americans in this country? I am an American.”

Four days earlier, Thompson and other Texas Democrats—a largely Latino and Black group—had arrived in the D.C. area in a strategic gambit, maybe even a desperate one, to leave their state’s Republican-controlled government without the total number of legislators required to pass laws. The reason: a slate of bills that would further restrict how and when voting happens in the state. Leaving the state is an option that Texas legislators last exercised in full almost 20 years ago, when Republicans—who had just recently come to power in the legislature—drew up a redistricting plan that looked likely to eliminate every Democrat from representing Texas in the U.S. Congress. In the end, the plan moved ahead.

Read more: In Texas, Democrats Go All In to Fight Voting Restrictions

This time, the caucus that left Texas has animated and irritated people across the political spectrum. Former Democratic U.S. Representative from Texas Beto O’Rourke managed to raise over $600,000 as of Thursday to cover what his team has described as the major costs of the Texas Democrats’ “fight against voter suppression.” And Governor Greg Abbott, a Republican who is reportedly interested in vying for the White House, has said publicly that he will have the lawmakers arrested when they come home.

“We need to find better ways than to fight each other over who is going to control what,” Thompson tells me later, not long after the charter bus we were riding on had taken us south on 14th Street, past the National Mall and the U.S. Capitol in the distance on our left, the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture on our right. “Right now, that’s about all we do.”

In the American imagination, Texas is a quintessentially Western, white and rural space, as Texas-born Harvard historian Annette Gordon-Reed describes in her book Juneteenth. But in reality, Texas—the last Confederate state to free the enslaved—is now home to some of the nation’s largest Latino and Black populations, as well as five of the nation’s 15 largest cities. Almost 58% of Texans identify as Black, Latino or Asian, and the big cities on the Eastern side of the state are home to about 86% of the state’s entire population. These are the people in Texas who tend to vote for Democrats.

But that majority has not yet translated into power. Even after decades of speculation about Texas turning politically blue—and a 2020 election in which Trump won the state by a smaller than expected margin—only 13 of the 38-member Texas Congressional delegation are Democrats. The state’s gubernatorial mansion, both state legislative bodies and all 27 state-wide offices are held by Republicans. A combination of gerrymandering, lagging voter registration among Latinos and a history of lower-than-average voter turnout have together allowed Republicans to exercise disproportionate power despite a shrinking voter base. That, Texas Democrats argue, is the real reason—not concern about election integrity, which supporters of the bills argue they will address—that Texas Republicans want to make it harder to vote, and in ways they believe are most likely to constrain Latino and Black Texans.

Thompson and the other lawmakers who decamped argue that the voting measures in question would mean that the already slow movement of political power in Texas—away from the state’s mostly white, rural and Republican districts, toward fast-expanding urban centers and their surrounding suburbs—will grind to an undemocratic standstill.

”I thought, for a long time, that racism—the really bad, violent, dangerous stuff—was in the past,” Thompson says. “I thought for a long time we were moving forward…but how strange it is that we are here, in the capital of a country known for innovation, to deal with the reality that some folks think it’s a crime if there’s an election and they don’t win. Some folks running the state of Texas think there’s something terribly wrong if it looks like some time soon, they won’t have all power and all control.”

The day before Thompson spoke so emphatically in Virginia, representative Celia Israel celebrated her 57th birthday, if it can be called a celebration so far from family and most friends. It was supposed to have been her wedding day, too. Another Texas Democrat, Israel—a Latina who represents a district that includes Austin— had planned to wed her partner of 26 years, Celinda Garza, in a ceremony on the Texas House of Representatives floor, then honeymoon in Big Bend National Park. Instead, she found herself here at the U.S. Capitol in a small room, all dark wood paneling and gilded light fixtures, enumerating just what was at stake in that power battle back home.

“We’re here to really just let you know how emotional this is for us,” Israel tells U.S. Representative Adriano Espaillat, an Afro-Latino Democrat from New York. “This is heartfelt. We love our state.”

Republicans so completely dominate policy in Texas right now, she begins to explain, that during this year’s regular session Texas lawmakers approved gun carrying without a permit and an abortion ban as early as six weeks gestation, without exceptions for rape or incest. While Israel doesn’t mention this, they also approved abortion restrictions that put some enforcement power in the hands of private citizens. And Abbott signed into law a state tax revenue penalty for major cities that remove any money from police budgets.

Texas representative Jarvis Johnson, a Black Democrat who represents a portion of Houston and who was there with Israel, picked up the thread. At least 53 of the more than 500 people arrested over the Jan. 6 insurrection live in Texas, according to a database compiled by USA Today, more than many other states. A video has been making the rounds of a meeting of Texas Republicans, in which they discuss a plan to send an “army” to heavily Black and Latino precincts in Houston where they claim voter fraud happens. That’s an idea that leaves Jarvis and others concerned about the possibility of armed and angry Trump supporters descending on their cities.

One of the Texas bills that prompted the lawmakers to leave would allow some of these same people to join the ranks of poll watchers, who may stand close enough to voters to observe their actions and hear any conversations—and who are allowed to do so while armed. Jarvis tells Israel and Espaillat that the possibility brings to mind the intimidation tactics once favored by Jim Crow-era local law enforcement and the Klu Klux Klan. For similar reasons, while he’s in D.C., Jarvis is worried about his 20 year old son, his namesake, driving a car registered in his name. Jarvis fears what could happen if his son passes the wrong police officer who has heard Abbott say the lawmakers “fled,” are wanted and subject to arrest upon sight. It’s language another Black Texas Democrat told me brings to mind the pursuit of runaway slaves and lost animals.

Read more: Texas Was Already One of the Hardest States to Vote in. It May Get Even Harder

There are also more subtle ways the Texas Democrats think the voting bills and the political fight over them could change who votes in the state. Around the country, Black and Latino workers are somewhat more likely to be assigned to evening and night shifts; one pending bill would eliminate 24-hour voting, an option offered in Houston in 2020 that some believe contributed mightily to higher than usual turnout. In addition, under the pending Texas bills, polling site workers—the people who administer election sites, often retirees—could face criminal penalties for honest mistakes.

The success of the Texas Democrats’ voting rights mission in D.C. is far from certain. There are at least three possible resolutions: Democrats could relent and return to Texas; that is unlikely to happen soon. Texas Republicans could agree to a compromise bill that addresses some or their concerns; this seems even more unlikely. Or, Congress could implement a federal law that bans or overrides some elements of proposals like the Texas bills. This is the possibility in which the Texas Democrats have placed their faith. And they’re not the only ones hoping for action in that realm: Congressional Black Caucus Chairwoman Joyce Beatty, an Ohio Democratic Congresswoman, was arrested on July 15 for protesting the failure of the U.S. Senate to take up the For the People Act or the John Lewis Voting Rights Act.

So Espaillat isn’t the only person at the Capitol whom the Texas Democrats are meeting with. Israel tells Espaillat that some of her colleagues had “a really good meeting” with U.S. Senator Joseph Manchin, a Democrat from West Virginia and one of two white Democrats, along with Senator Kyrsten Sinema from Arizona, who have thus far refused to vote to end the filibuster. Without that, any support both lawmakers have expressed for new federal voting rights legislation has a major limit; voting rights bills won’t make it to the Senate floor for a vote and cannot become law. Both Manchin and Sinema hail from states where voters are almost evenly split between the two major parties. There have also been meetings with Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi, Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer and Vice President Kamala Harris. And Texas Democrats have also joined in protest actions and press conferences with a number of civic and political organizations including Black Voters Matter. As Texas representative John Bucy III, a white Democrat who represents Austin and several suburbs, put it, the group is taking just about all meetings. Bucy is prepared to stay in Washington, D.C., so long that he brought his entire family. Still, many political analysts believe the Texas Democrats are unlikely to prevail.

“My goal is for us to not let the perfect be the enemy of the good,” Israel tells Espaillat. “Let’s find the three or four good things that we can get through these senators and let’s move forward.”

Then it’s back to the hotel, followed by a return to the Capitol Hill area for a visit to the U.S. Supreme Court, via a misdirected Uber that first goes to the U.S. Court of Appeals. It’s just after 5:00 p.m. and Israel and some of her colleagues, a group of women lawmakers, want to use the building as a backdrop to record videos for social media. After all, that’s where in 2013 the court eviscerated part of the Voting Rights Act, making way for bills like those proposed in Texas.

“Gay marriage was made legal [here] in 2015,” Israel says, when it’s her turn to speak. “I was supposed to get married but I’m a runaway bride. And I’m running from a really bad governor and running from a state that has so many misplaced priorities…This is our job right now, to speak up for the state that we love and the country that we love.”

Aug. 6 will mark the 56th anniversary of the day when another Texan, then President Lyndon Johnson, signed that 1965 voting rights law. He and some of the lawmakers who backed it were prompted in part by the violent way that voting rights protesters were confronted, beaten and nearly killed on their march from Selma, Ala. Back in 1965, a young Mitch McConnell was there to watch the Voting Rights Act become law. He supported its contents and voted to renew it after he joined the Senate. For almost five decades, the Voting Rights Act required states with a history of voting discrimination, including Texas, to seek federal approval for voting-related changes. The Supreme Court stuck down that provision. As Senate Majority Leader, McConnell in 2020 refused to hold a vote on a new version of the Voting Rights Act.

Inside the antechamber where they met, Israel, Jarvis, Espaillat and his aides had all gone maskless, in keeping with CDC guidelines for those who have been vaccinated against the novel coronavirus. Days later, Israel became one of several Texas Democrats in the delegation to test positive for a breakthrough case of COVID-19. In-person activity largely came to a halt. But, before it did, Thompson, the Texas Black caucus and two members of the Mexican American caucus had their event in Virginia.

Read more: Texas Lawmaker in D.C. on Testing Positive for COVID-19: ‘Let This Be a Reminder’

There, Thompson tells me it was the first time in at least 30 years she can remember crying, in public about politics. Someone gave her a tissue.

Thompson is a practicing lawyer, not afraid of a leopard-print blazer. When she talks politics, it’s clear that the woman known as “Ms. T” has seen a lot of history and plans to shape the future.

“We deserve the same rights and consideration that everybody has,” Thompson says. But a deep level of “inhumanity” runs through so much of American politics, she says—that, and power games.

Thompson tells me that she, like anyone might, once entertained dreams of moving up the political ladder, but that moments like this one remind her that she is where she needs to be. The national attention the Texas delegation is garnering is nice, but it will only matter if it comes with a successful defense of voting rights, the cornerstone of a truly inclusive and representative democracy, she says.

When the bus stops again, we’re at The Park at 14th, one of those downtown restaurants that, before the pandemic, made brunch a big part of D.C. weekend culture. State representative Jasmine Crockett, a freshman Texas lawmaker and Black Democrat who represents a district that includes parts of the Dallas area, stands near the door making calls as other lawmakers stream inside. She’s wearing a red blazer, matching Converse and carrying a black purse embossed with the words “PROTECT BLACK PEOPLE.”

Crockett, the only Black freshman this session, had told me that what shocked and troubled her most in this, her first year in the legislature, were the obvious assumptions about who should have power over what happens in Texas—and the lengths to which people were willing to go to maintain that status quo.

“I have no doubt in my mind what’s going on,” she said. “[Republicans] see their power dissipating. It’s a matter of, ‘if we don’t stop those Black people and them brown ones from deciding to vote, then we’re screwed.’”

This session, Republicans voted to restrict the ability of gang members—presumed to be “Black and brown,” Crockett says—to carry guns, but refused to curtail the gun rights of those who meet the federal definition of a white supremacist. This was the moment where Crockett found herself in tears on the Texas House floor.

“That was the one lesson I learned this session,” she says. “There is no logic in the leg.”

And so the Texas Democrats are planning to stay, for some time. They have until the Senate’s session ends on Aug. 6 to convince federal lawmakers to do something to protect voting rights. And yet many political observers think that the dramatic act of leaving the state ultimately cannot be sustained or effective. The governor has called a second special session that could run into early September. Eventually, in September, the regular session will start up again.

Inside The Park, while trying to figure out where in D.C. she can go for her weekly wash and set, Thompson inadvertently begins to hold a kind of advisory court for younger, Black women in the state-lawmaking world. If Democrats had managed to flip more seats in the Texas House, Thompson would likely be it’s speaker right now. Instead, a Maryland Delegate sitting immediately to Thompson’s right asks her how long she’s been in the legislature.

“Fifty years,” Thompson says.

“And, you are not exhausted?” the Maryland lawmaker asks.

In Maryland, Democrats had a supermajority in 2020. So when lawmakers took on police reforms during that session, Democrats resolved to let Republicans have their say, to debate or interrupt as little as possible, then pass the legislation in question. But it became trying for the Democratic lawmaker to hear her mostly white Republican colleagues opine at length about things like the financial needs of officers and their families, without so much as a mention of the toll the disproportionate number of Black and Latino people killed by police takes on those families. A Virginia lawmaker seated to Thompson’s left, who at the library gave an impassioned speech about the danger of rolling back civil rights gains, commiserated. She said she found herself oddly grateful that the pandemic forced their police reform hearings to take place over Zoom, a space where she could participate, camera off, eyerolls obscured.

Didn’t Thompson feel it too?

“No,” Thompson says as a smile spreads across her face.

What these women need is self care, she says, to work hard for the right things and the clear conscience that brings. Yes, there are frustrations: For example, many aspects of a Texas policing reform bill Thompson named in honor of George Floyd did not survive Texas House Republican opposition. Some did, after Thompson told her colleagues she wants the same freedom they have, not to live in fear their children will be killed by police, but even those measures died in the Texas Senate. She hasn’t given up, so she’ll need to get back to Texas eventually, where there is work to be done.

“I still wake up,” she says, “ready to kick ass every day.”

Correction, July 26

The original version of this story misstated whether Senators Manchin and Sinema have refused to vote for new federal voting rights legislation. While their opposition to filibuster reform is seen as effectively blocking such legislation from passing, each has also expressed support for at least some version of a voting rights bill.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com