Jackson Avenue is the main road that cuts through Oxford, Miss. At its northern limit, it circles the Ole Miss campus where Raven Saunders had spent the past three years as a student athlete. At its western end, Jackson splits into a T junction populated by a cluster of familiar American fast food restaurants and retail chains: a Walmart Supercenter, a Home Depot, a Popeye’s, a Chick-Fil-A.

Saunders, a senior at University of Mississippi and a star shot putter on the school’s track and field team, knew the intersection well. Turn right, and the road led home. Turn left, and the highway hugged a steep drop-off floating above towering trees below that Saunders had found herself thinking more and more about in January of 2018.

Her last year in college hadn’t been easy. She won four NCAA titles while at Ole Miss, and finished fifth at her first Olympic appearance in Rio in 2016. But after an injury in 2017, she couldn’t defend her NCAA title and came in 10th at the world championships. The pressure of balancing academics and sports at an elite level was starting to tear her apart. Because the track season ended as the next school semester began, she never had a true break as a student-athlete—every year, less than a week after returning from world championships, she was back in the classroom. After competing at the Olympics in Rio, she had to pick up her studies two days later.

“I was drained,” she tells TIME, days before competing to make her second Olympic team in June. “I would cry a lot and go into isolation. I had suicidal ideation. I thought about different ways to make it happen.”

One morning in January 2018, those thoughts hijacked her brain completely. “It was just too much,” she says of the building pressure and depression. Knowing she had a full day of school, practice and other appointments that started at 8:30 a.m., she woke up in a daze and didn’t leave her house until 11:30 a.m.. Instead of driving where she needed to go and checking things off her to-do list, she drove to those places and kept going. “I rode past every place I needed to stop and get things done, and kept going,” she says. “I felt it was like a goodbye and I was going to see everything one last time.”

Driving west on Jackson Ave. toward the junction, Saunders was ready to take the left toward the drop-off. Something, however, prompted her to text her therapist, whom Saunders trusted completely. Saunders told herself that if her therapist didn’t answer by the time she reached the Walmart, she would take the left hand turn.

Just before Saunders got to the light, her therapist responded.

“She texted back, ‘I got you, just breathe, calm down,” says Saunders.

Saunders turned right, went home and cried. At her therapist’s suggestion, she went to the school and informed her coach about what had just happened, and asked for help. Together with her therapist, he helped Saunders get admitted to a facility for two months. “Man, that was some of the toughest work I’ve ever done,” she says of that stay.

She credits it, however, with saving her life, and with teaching her the skills she now relies on to work through her dark moments. On June 24, at the sweltering U.S. Olympic Track and Field Trials in Eugene, Ore., Saunders launched the shot put for a personal best throw and made the team.

While their achievements and glorious exploits, chronicled in broadcasts around the world, may make it seem like Olympic athletes live charmed and angst-free lives, that’s far from the case. Saunders’ story is hardly unique. More athletes are reporting mental health issues such as anxiety, depression, psychiatric conditions and eating disorders.

The exact percentage of Olympic athletes with mental health concerns isn’t clear, since it hasn’t been recorded. But given the incidence in the general population, coupled with the added pressures of the pandemic and Olympic competition, “the majority of athletes should be using mental health support,” says Dr. Naresh Rao, D.O., head physician for USA Water Polo and member of the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Committee (USOPC) medical team at the Tokyo Olympics. “If you look at the percentages of people who have mental health illness in general, it ranges from 40% to 50%. Throw in the pandemic, and the fact that many of these athletes are teenagers or young adults, and you start to see the percentage could go up to as high as 70%.”

In some ways the four-year cycle of fame and fallow is similar to the highs and lows of an addictive drug. The withdrawal after the exhilaration of competing, no matter the outcome, is a mental crash that can hit athletes hard. It’s not just the sudden fame that can be disorienting, but the often disturbing realization that after years and sometimes decades of training and devoting themselves to perfecting their sport, they’ve allowed themselves to be defined by their results and their medals, or lack thereof, and may have lost themselves in the process.

“I just kept coming back to the idea that I just don’t know who I am without gymnastics,” says gymnast Sam Mikulak, who will compete in Tokyo on his third U.S. Olympic team. During the pandemic, the time away from the gym forced him to confront what he had been dismissing for years. “I was going through an identity crisis and asking myself how I can find happiness, where is the happiness if I don’t have this sport.”

Read more: COVID-19 Shutdowns Have Taken a Massive Toll on Elite Athletes’ Mental Health

And yet, Olympians’ mental health has never been a key concern for the sports governing bodies that oversee them. “It’s as if mental health issues weren’t there, and wasn’t talked about,” says Saunders. “If you got a problem, you deal with it. And if you have any type of mental health problem, people think you’re crazy or something is wrong with you, or you’re off. That’s how I grew up thinking about it.” Physical injuries have long been managed with detailed protocols and services, but coaches and event organizers rarely considered the mental state of athletes, much less ensured there were resources available to address any issues. Tennis star Naomi Osaka highlighted this deficiency by pulling out of the French Open in May, after backlash over her decision not to participate in any press conferences to protect her mental health.

But heading into Tokyo, that may be starting to change. Admissions like those from Michael Phelps, who admitted he too experiences depression and was suicidal after his fourth Olympics, have prompted the International Olympic Committee (IOC) and national Olympic bodies including the USOPC to directly address mental health in the same way they advise athletes on nutrition and recovery from physical injury. Tokyo will mark the first time the IOC has guidelines for athletes and their coaches to educate, screen for, and manage mental health issues, the work of independent experts it convened on the subject for the first time before these Games. The USOPC also has more concrete and detailed mental health resources for Team USA athletes, including deeper screening for potential issues that athletes themselves might not be aware of or willing to admit, and referral and treatment options if they need them. Team USA in Tokyo will also include, for the first time, four mental health professionals—a psychologist, two psychiatrists, and a social worker— and each Team USA sport will also have its own dedicated psychologist. The British Olympic Association has a similar team of mental health professionals traveling to Tokyo with Team Great Britain for the first time, while Softball Australia will monitor athletes’ sleep habits on an app as an indicator of potential issues.

“Just to know that [these resources] are on hand if you need them is awesome, especially for the younger kids growing up in sports who can reach out and get help if they need it to be better competitors and better athletes,” says gymnast Simone Biles, who works with her own therapist.

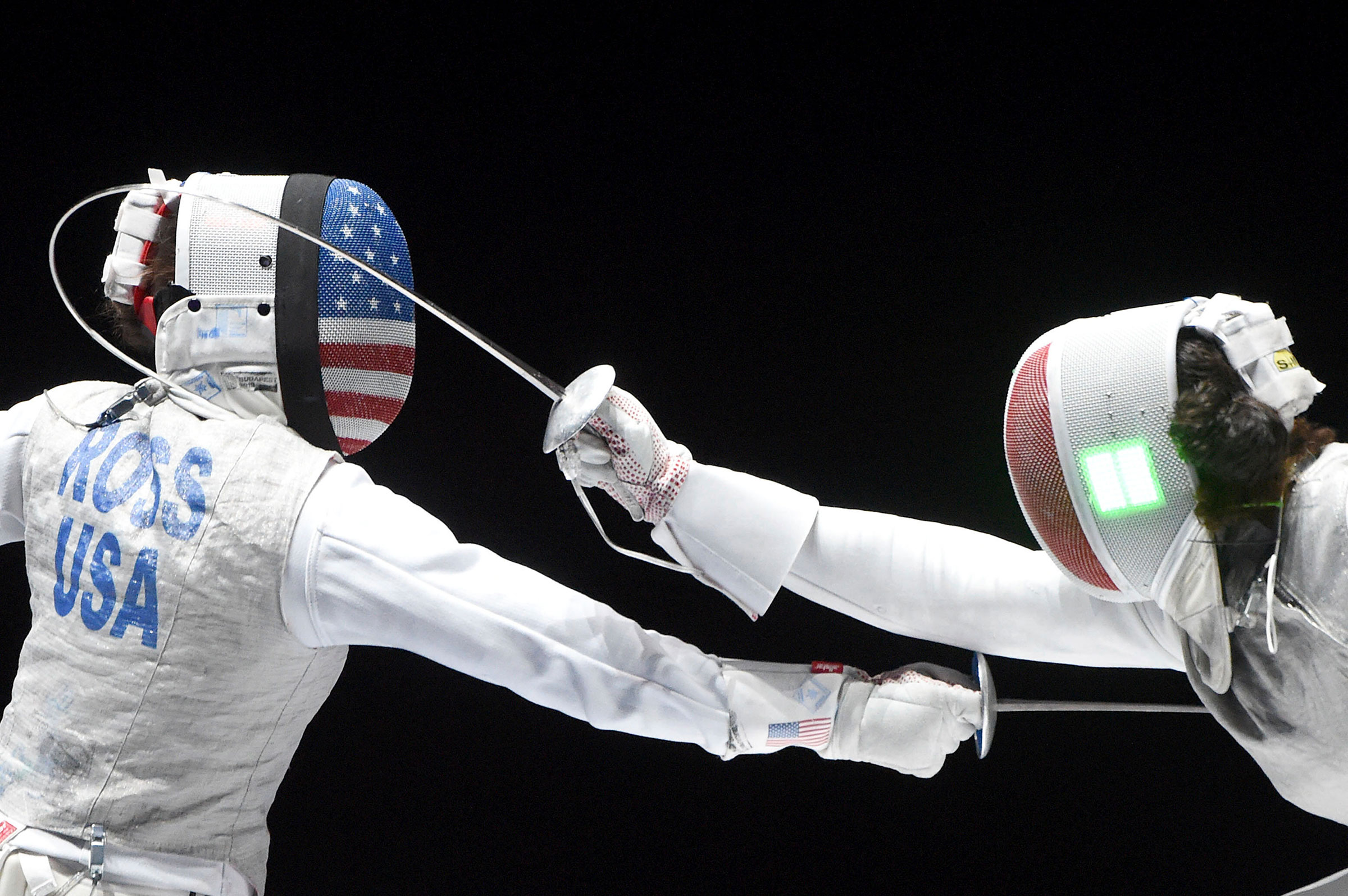

“It’s a work in progress, and we could certainly be doing things better to improve mental health services, but things are moving in the right direction in terms of supporting athletes with regard to their well being and mental health,” says Nicole Ross, a fencer competing in Tokyo who serves as an athlete representative on a USOPC mental health task force.

Stigma remains a problem, however, since the mantra particularly at the elite level is grit your teeth and push through any pain, physical or emotional. “The athletic culture in general is one in which you are driven to continuously push your body and in some cases your mind to the maximum potential,” says two-time Olympic swimming gold medalist Simone Manuel, who revealed at Olympic Trials in June that she experienced depression related to overtraining syndrome. Only recently with prominent athletes like Phelps and Saunders sharing their own struggles with mental health issues is that taboo slowly being eroded. As more athletes vocalize their own experiences, organizations like the USOPC are also finally devoting more resources to addressing the mental health of their athletes and providing them with the tools to improve their mental well being.

‘Athletes are not perfect, flawless gods’

“Five years ago, mental health among elite athletes was not a very often-discussed topic,” says Dr. Claudia Reardon, professor of psychiatry at the University of Wisconsin. If there was any focus on athletes’ mental health, it centered around performance and ways to optimize results on the field. “Most of the emphasis when it came to mental health was around sports psychology and performance, and offering resources to help you perform at your highest level,” says Ross. “Occasionally in the health history [questionnaire] there might be some questions about mental health but they were sort of hidden, and weren’t prominent.”

It wasn’t until 2018 that the IOC convened its first dedicated panel of experts to address all aspects of mental health—the IOC had already tackled other topics such as nutrition and serious physical injuries, but never mental health. The IOC reached out to Reardon and Dr. Brian Hainline, chief medical officer of the NCAA, to co-chair its first working group on the topic. Over several meetings since, Reardon says the group has worked to reach consensus in addressing the biggest barriers in mental health, including stigma and access to resources, across different countries with differing societal norms around mental illness. “When we looked at the world’s research, it was not a surprise to any of us that, lo and behold, elite athletes suffer from depression and anxiety at rates at least equal to—and in many cases may even exceed—general population rates,” says Reardon. “Athletes are not perfect, flawless gods.”

One critical recommendation of the consensus statement focused on the first step in addressing mental health issues—recognizing and diagnosing it in the first place. In September 2020, the working group published two screening tool questionnaires to better identify potential issues among elite athletes. One, the Sports Mental Health Assessment Tool (SMHAT), was meant for medical professionals to use, and another, the Sport Mental Health Recognition Tool (SMHRT), was designed to help coaches, friends and family of athletes to identify mental health signs and symptoms.

“We can’t rely on athletes universally to bring up and discuss issues related to mental health,” says Reardon, pointing to the long-standing stigmas within the community. The key was to suggest that the SMHAT be part of routine physicals that athletes are used to getting before their seasons start or in order to enter major competitions. That normalizes mental health more by putting it on par with physical evaluations, and doesn’t require the athlete or anyone close to the athlete to specifically request or flag a possible mental health issue.

The survey is crafted to raise alarms for any signs that athletes might be a harm to themselves or others, and to immediately connect them with the appropriate support. After the USOPC began using the screening tool with USA Swimming and USA Soccer, Jessica Bartley, the USOPC’s first director of mental health services, says “I was surprised by the number of athletes who were identified as having mental health concerns.” About 80 athletes, or 58%, of the 165 who filled out the questionnaire were identified as potentially having a mental health issue, and Bartley called each to see if they were already getting the help they needed, and, if not, to connect them to a new registry of 150 psychologists and therapists that the USOPC launched in April. The tool identified four athletes as potentially at risk of self-harming behaviors or having suicidal ideation, and Bartley reached out within 15 minutes of receiving their results. “They were all a little surprised when they got a phone call right away,” she says. All four were already working with mental health professionals, and Bartley made sure that they were satisfied with the support they were receiving.

If those athletes hadn’t already had a mental health team, Bartley would work with them to create one, including providing financial support for any therapy or residential care they might need. In May, Bartley worked with an athlete who needed treatment for an eating disorder, and helped that athlete find the appropriate treatment center as well as coordinate lodging and payment through insurance, which is covered by a Medical Assistance Fund created by a USOPC donor for $1.5 million that is dedicated to mental health needs.

Standardizing that type of reimbursement and access is trickier in other parts of the world where mental health services either aren’t as widely available or financially supported. “It’s all well and good and easy for me to say that everyone should have access to an experienced sports psychologist,” says Reardon “But that’s not relevant in the majority of the world. So it requires us to think about community healers, religious leaders and others who may be in a position to help notice mental health concerns and intervene in culturally appropriate and sustainable ways.” So the IOC is also working on building a network of mental health professionals, including culturally relevant resources such as faith healers and other community leaders in countries around the world, to whom it can refer athletes if needed.

‘Our vulnerability as athletes is going to make us stronger’

The second screening tool, the SMHRT is designed for coaches, friends, family members and any non-medical professional who might be close to an elite athlete. Many people who aren’t formally trained in mental health aren’t comfortable approaching athletes even if they sense they are struggling, out of fear they aren’t qualified to help them. “When they don’t know what to do, they don’t do anything. But by not saying anything doesn’t mean they don’t care,” says Reardon. The SMHRT provides exact language for guiding that discussion, and initiating a critical conversation that could save that athlete’s life.

It was just such a conversation that finally helped four-time Olympian Allison Schmitt to face the darkness that had been shadowing her for years.

To swimming fans, Schmitt is “Schmitty,” easy-going and perpetually smiling, known among teammates for her corny jokes and an easy laugh. She admits that at her Olympic debut in 2012, she swam better than she even expected, and became an instant celebrity when she returned home to Michigan and then in Baltimore, where she trained alongside Phelps, who became a close friend. The attention and whispers of people who recognized her on the street were unnerving, and Schmitt increasingly felt exposed and uncomfortable with her newfound visibility. But it was hard to admit those feelings. “Everything has always gone my way, and I was very grateful for the life I had, the opportunities I had, the successes I had,” she says. “So it was very hard for me to accept that I was struggling because I didn’t want to seem ungrateful.”

Instead, Schmitt bottled up the growing sadness and mental anguish. “It got to the point where I was lying in my bed crying because I didn’t know if I wanted to live any more. I didn’t want to die, I just didn’t want to be living through what I was going through any more.” Months after returning from London, Schmitt’s uncle died by suicide, and “it wasn’t really talked about,” she says.

Then, three years later, Schmitt’s 17-year old cousin died by suicide as well. A star basketball player on her high school team, she never discussed her mental torment with Schmitt, nor did Schmitt share her own feelings of inadequacy and purposelessness. To this day, it haunts Schmitt, who gets emotional thinking about what could have been. “That suicide really turned my eyes,” she says. “If she would have shared with me what she was going through, could I have helped? And if I had shared with her what I was going through, maybe she wouldn’t have felt so alone.”

Determined not to have her cousin’s death be in vain, Schmitt decided to share her own experience with depression, in the hopes that others would feel more comfortable than she did in admitting they need help and in getting that help.

Hearing from teammates or other elite athletes is critical to building a new culture around mental health in high level sports, says Ross, who makes sure that her USA Fencing teammates are aware of the mental health resources that are available to them. “I honestly think it will take individual athlete ambassadors to go directly to their sport and talk to teammates and the national governing body staff about what resources are available, and how they were able to successfully use those resources,” she says. “That grassroots effort is what it is going to take to reach the largest number of athletes.”

And that shouldn’t end when the competition does. For the first time, the USOPC has created a support group for athletes who don’t make the team, as well as those who struggle with readjusting to life after retiring. Bartley and her team are also reaching out to athletes every time they experience a major injury or life event that could impact their training or career goals. “That’s never happened before,” says Rachel Flatt, a member of the 2010 Olympic figure-skating team and now an athlete representative of the USOPC mental health task force.

Learning to cope with the post-Olympic period, whether it’s the four years before their next Olympics, or retirement, is a growing focus of these mental health efforts. When the pandemic lockdown disrupted gymnast Mikulak’s regular training schedule, he finally confronted something that he had been pushing aside in recent years: what he would do once he stopped competing. “It was scary to think what was going to happen after I retire when I don’t have my gymnastic goals any more that I was constantly pushing for and seeking,” he says. “All of that was going to be gone. The more I looked into my future, the more fear I felt. I just really freaked out.”

He started working for the first time with a sports psychologist to address his anxiety, and his broader struggle with his sense of identity outside that of being a gymnast. Together they confronted why, at critical moments when Mikulak had been just a performance away from achieving his dream of winning an Olympic medal, he made costly mistakes. “I was trying to be the most scientifically perfect specimen of gymnastics,” he says of his three previous Olympic experiences. “I felt if it doesn’t happen here, it will never happen anywhere else. So when the pressure I felt was at its greatest, at the 2016 Games, and I had a couple of chances for a medal, I fell short. I was focusing 100% on my physical ability and I did nothing for my mental fitness.”

That changed thanks to his work with his therapist, so preparing for the Tokyo Games, he says, was very different. “I could tell, as we were getting closer to Tokyo, that I was starting to feel the same pressure. But this time, my expectations for them is to have no expectations,” he says. “I’m going out there with the intention of doing nothing more than I can do in that moment, and be proud of that, and happy with that. I’m going to go out there on my own terms, and not on anyone else’s.”

Like Mikulak, Schmitt has found a new power in speaking out about her journey with depression. “I am personally accepting that speaking out and getting help and being vulnerable is strength,” she says. “And that strength has helped me. Our vulnerability as athletes is going to make us stronger in the long run.”

If you or someone you know may be contemplating suicide, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255 or text HOME to 741741 to reach the Crisis Text Line. In emergencies, call 911, or seek care from a local hospital or mental health provider.

Read more about the Tokyo Olympics:

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com